Since the discovery of LSD’s mind-blowing properties (in the 1940s-50s) there have been several waves of research, clinical trials, and of course “recreational” tripping with LSD and its close cousins, mescaline and psilocybin (magic mushrooms). The interest and excitement of the scientific community was pretty much squelched in the US by legislation making LSD strictly illegal, a policy that continues to this day. But more enlightened countries have resumed research on LSD and psilocybin. These substances are of great interest because of their (probable) clinical value in fighting depression, chronic pain, chronic anxiety, fear of death, and — you guessed it — addiction, especially alcoholism. Take a look at this intriguing documentary trailer. Meanwhile, recreational use has continued over the decades, trending and receding in different countries at different times.

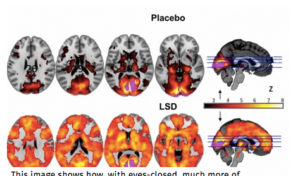

We are also finally beginning to understand LSD’s impact on the brain. A recent, multi-layered study showed that “under [LSD], regions once segregated spoke to one another.” In other words, psychedelics open lines of communication between neural regions that normally stay hived  off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain

off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain  synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from this article). Here’s a slightly more technical but excellent review of the study.

synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from this article). Here’s a slightly more technical but excellent review of the study.

What’s most interesting here for addiction? Well, for one thing, David Nutt has long functioned as a lead adviser to the UK government on drug policy (the equivalent of a drug czar in the US?) And he was the lead author of the study! Nutt is no nut. He’s smart, influential, highly respected as a scientist, and progressive in his views and advice about drug use. So if David Nutt is cool about exploring how acid disintegrates neural barriers, then you know that psychedelics are no longer being sneered at or ignored by scientists, that they’re being recognized as potent tools for revamping thought and perception, essentially breaking neural habits — if only for a few hours.

So what’s the word on the street? Well you’ve probably heard of ayahuasca, and if you haven’t you should really google it. You can start here, or start with Wikipedia. Ayahuasca (or its underlying molecule, DMT) is the psychedelic of the  present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world.

present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world.

Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté, has become one of its strongest advocates. Maté is convinced that ayahuasca is the most direct and effective way for addicts to uncover and come to accept the pain and confusion they’ve kept inside and which perpetuates the emptiness and anxiety that locks in their addiction. He also sees it as a gateway to an uncluttered, even blissful, sense of the universe — which sounds like the kind of universe you’d choose not to damp down with heroin. Maté emphasizes the importance of taking ayahuasca in a tradition-based ceremony with an experienced shaman. He has set up various supervised ayahuasca retreats, first in Canada (specifically targeted to the addict community in Vancouver) and now (that it’s been banned in Canada) in Central America.

Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté, has become one of its strongest advocates. Maté is convinced that ayahuasca is the most direct and effective way for addicts to uncover and come to accept the pain and confusion they’ve kept inside and which perpetuates the emptiness and anxiety that locks in their addiction. He also sees it as a gateway to an uncluttered, even blissful, sense of the universe — which sounds like the kind of universe you’d choose not to damp down with heroin. Maté emphasizes the importance of taking ayahuasca in a tradition-based ceremony with an experienced shaman. He has set up various supervised ayahuasca retreats, first in Canada (specifically targeted to the addict community in Vancouver) and now (that it’s been banned in Canada) in Central America.

I don’t consider myself an addict anymore, but I still have addictive tendencies, ruminative thoughts, sporadic depression, and an attraction to alcohol (within the bounds of social drinking) to help ease my discomfort with myself. So I didn’t take ayahuasca to treat an addiction. Rather, I took it because I wanted to experience its power and potential — with some hopes that it would help free me of lingering anxieties and depression (not without some hard work — as Maté also emphasizes). I had taken a lot of LSD and related drugs when I was young,  in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out.

in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out.

There are ayahuasca ceremonies in Europe every year, most if not all supervised by experienced shamans and their assistants. I’ve now taken ayahuasca five times (in five years) and I doubt I’ll ever take it again. It’s just too much for this old brain. Ayahuasca isn’t exactly fun. It can be disturbing, it can be hard work (just to endure), it can make you shit your guts out and puke violently (politely called purging). But it can also be wonderful, enlightening, and (I think) constructive in a big way — if done in the right circumstances with the right follow-up.

I’m out of space here, so I’ll tell you about my own experience in my next post. Coming soon.

Meanwhile, warning! If this little introduction makes you want to run out and try ayahuasca, do not even consider doing it without a knowledgeable, experienced shaman or other guide. You don’t do this in your high-rise apartment one night, or at parties. And you don’t do it alone. Oh and if you find a proper ceremony to attend and feel you’re ready, make sure to bring an extra pair of undies.

Leave a Reply