I just got back from a two-day meeting on animal models of addiction. And here’s what I learned: animals way way down the evolutionary ladder also like opioids and psychostimulants. And flies like alcohol. That should make us feel less lonesome.

I was asked to be the keynote speaker for the meeting, because the organizers thought that animal researchers should learn more about human addiction. Well, it was a nice idea, I got a free trip to Chicago, but my work may just be too distant from what these folks think about. They study “addiction” — or  more simply drug seeking — in, for example, crayfish, sea-slugs, something called zebrafish, and the common fruit fly (drosophila). Seriously. They listened to what I said about human addiction. I stressed cognitive-emotional factors like “now appeal” and “ego fatigue”, I stressed how difficult it is to make good decisions in stressful environments, especially when memory serves up powerful associations between getting high and relief. I talked about the symbolic appeal that intensifies addiction for us humans. How we’re addicted to what the drug means to us more than to the physiological change it produces. They listened, but I don’t think they got it. And when it came to my spiel about the internal dialogue, the “addict self” and so on, it’s like we were on different planets.

more simply drug seeking — in, for example, crayfish, sea-slugs, something called zebrafish, and the common fruit fly (drosophila). Seriously. They listened to what I said about human addiction. I stressed cognitive-emotional factors like “now appeal” and “ego fatigue”, I stressed how difficult it is to make good decisions in stressful environments, especially when memory serves up powerful associations between getting high and relief. I talked about the symbolic appeal that intensifies addiction for us humans. How we’re addicted to what the drug means to us more than to the physiological change it produces. They listened, but I don’t think they got it. And when it came to my spiel about the internal dialogue, the “addict self” and so on, it’s like we were on different planets.

Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to

Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to  them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by

them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by  which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company.

which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company.

But how do we make sense of the fact that gambling, porn, internet use and sports can also be highly addictive? It seems we somehow have to draw a line from the physiological changes that opioids and stimulants provide, up to the level of “I like this — I want more!” and then back to all kinds of addictive behaviours as well as drugs themselves. Then maybe we can figure out how behavioural addictions — in fact all addictions — really work.

What about the genetics of addiction?

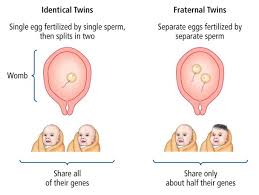

I also learned more about the genetics of addiction. For years I’ve been arguing, much like Maia Szalavitz, that the oft-cited 50% heritability of addiction is mostly due to personality traits. There’s certainly no gene or gene cluster that predicts addiction, though there are genes that can make one more or less sensitive to specific substances, like opioids (the dynorphin receptor gene) and alcohol (which is more complicated). Yet personality traits, which can be genetically shared, predict addiction itself. The most clear-cut example is impulsive personality. More impulsive people are more likely to try drugs, or drink (or drink more) at younger  ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average.

ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average.

Yet I’ve always emphasized environmental effects. They are so huge and so obvious. From Gabor Maté’s oppressed native populations, to Rat Park, to the ACE studies…yeah, it’s pretty obvious that difficult or stressful or oppressive environments predict addiction. And most of my clients who’ve struggled with addiction have had really shitty times during their childhood or adolescent years. Young people adapt to abuse (physical, emotional, or sexual) or neglect (like rejection by a parent or step-parent) by trying to make themselves feel better with substances. It’s called “self-medication.” It’s not rocket science.

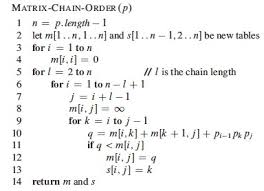

But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit.

But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit.

One of the scientists speaking at the conference, Daniel Jacobson, showed us that he can predict fine gradations of autistic behaviour, by data crunching (on the world’s fastest supercomputer!) hundreds of thousands of genetic variables interacting with each other and with thousands of environmental variables. So — once we get better at quantifying environmental impacts (like isolation, abuse, bullying) we may indeed be able to predict addiction, not from genes themselves but from the interplay between gene networks and environmental challenges.

One of the scientists speaking at the conference, Daniel Jacobson, showed us that he can predict fine gradations of autistic behaviour, by data crunching (on the world’s fastest supercomputer!) hundreds of thousands of genetic variables interacting with each other and with thousands of environmental variables. So — once we get better at quantifying environmental impacts (like isolation, abuse, bullying) we may indeed be able to predict addiction, not from genes themselves but from the interplay between gene networks and environmental challenges.

Still, even with all the fancy computing power in the world, I think that environmental challenges will remain impossible to quantify. As I argued with this

dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

How to conclude? Two things. First, addictive drugs are addictive because of what they do to the nervous system of animals, lots of kinds of animals, not just us. But we humans build all this symbolic stuff — like need fulfillment, warmth, the sense of being in control — on top of that primal impact. Second, we may never be able to accurately compute who becomes addicted, but your chances surely derive from what you were born with (inheritance) interacting in hugely complex ways (development) with the sting of environmental misfortune.

Addendum: I realize this post covers two seemingly different topics. Yet they’re deeply connected. Our genes are the basis of our humanity, but we still carry these mechanisms of reward-seeking that go back hundreds of millions of years. After all these aeons of evolution, we still haven’t been able to discard the code for these mechanisms. We still need them. They’re that basic. Think about it.

Leave a Reply