………………

There are things we believe we know. Accepted truths that can’t be wrong. We see the evidence of these truths daily. These are the things we don’t need a citation for, the words we don’t list in the table of definitions, the questions we don’t even need to ask. But what if we have been fooled? What if everything we are sold to believe about drugs is, at some level, wrong?

There are things we believe we know. Accepted truths that can’t be wrong. We see the evidence of these truths daily. These are the things we don’t need a citation for, the words we don’t list in the table of definitions, the questions we don’t even need to ask. But what if we have been fooled? What if everything we are sold to believe about drugs is, at some level, wrong?

There are some accepted truths that I question, in order to challenge my students. Here is one example:

Me: “What is a drug?”

5th year Med student: “Uuurgh! We all know what a drug is.”

Me: “So then tell me…”

Google kicks in. The class frantically searches “What is a drug…”

Student: “A drug is… drugs are chemical substances that affect or alter the physiology when taken into a living system. They can either be natural or synthetic.”

Me: “What about food…”

Frantic typing.

Students: “Except food!”

Me: “What about magic mushrooms? What about coffee? Sugar?”

Student: “A drug is an illegal substance that some people smoke, inject, etc. for the physical and mental effects it has (Oxford learners).”

Smug smile…for a second.

Me: “So Cannabis is no longer a drug in South Africa, Canada and parts or Australia? Which scientific body decided that?”

Student: “I’m sorry, but I didn’t come to this class to discuss philosophy. I came here to learn how to treat drug addicts!”

“Well, if there are no drugs, how can there be drug addicts?”

Here are some quotations, by people far smarter than me, from my course material.

From an interview with Jacques Derrida:

“…there are no drugs ‘in nature.’ There may be natural poisons and indeed naturally lethal poisons, but they are not as such ‘drugs.’ As with addiction, the concept of drugs supposes an instituted and an institutional definition: a history is required, and a culture, conventions, evaluations, norms…There is not in the case of drugs any objective, scientific, physical (physicalistie), or ‘naturalistic’ definition …the concept of drugs is not a scientific concept, but is rather instituted on the basis of moral or political evaluations: it carries in itself both norm and prohibition…it is a decree, a buzzword.”

“…there are no drugs ‘in nature.’ There may be natural poisons and indeed naturally lethal poisons, but they are not as such ‘drugs.’ As with addiction, the concept of drugs supposes an instituted and an institutional definition: a history is required, and a culture, conventions, evaluations, norms…There is not in the case of drugs any objective, scientific, physical (physicalistie), or ‘naturalistic’ definition …the concept of drugs is not a scientific concept, but is rather instituted on the basis of moral or political evaluations: it carries in itself both norm and prohibition…it is a decree, a buzzword.”

“Whatever the origin of the U.N. Drug Treaties, and whatever the official rhetoric about their functions, the best way to look at them now is as religious texts… Books by Andrew Weil, Norman Zinberg, and Lester Grinspoon have been listed on drug warrior websites in the U.S. as ‘dangerous’ while ‘concerned’ citizens are encouraged to demand their removal from local libraries. The more detail in which the heresies are spelled out, the more the security of the Faith is established.”

“1. ‘Drug’ (as well as ‘narcotic,’ and similar terms…) does not denote a scientific or pharmacological category. It points, rather, to a category that reflects how a society has decided to treat a substance… 2. The category to which a substance is assigned affects how people who ingest that substance are treated and that, in turn, affects what the substance in question does to and for them. 3. Therefore, the solution to the problem is to redefine the phenomena involved. But this simple solution is not available because the power to define is concentrated among people [with] no incentive to take that easy step.”

“The belief in drug-induced addiction has acquired the status of an obvious truth that requires no further testing. But the widespread acceptance of this belief is a better demonstration of the power of repetition than of the influence of empirical research, because the great bulk of empirical evidence runs against it. Belief in drug-induced addiction may have deep cultural roots as well, since it is a pharmacological version of the belief in ‘demon possession’ that has entranced western culture for centuries.”

“The belief in drug-induced addiction has acquired the status of an obvious truth that requires no further testing. But the widespread acceptance of this belief is a better demonstration of the power of repetition than of the influence of empirical research, because the great bulk of empirical evidence runs against it. Belief in drug-induced addiction may have deep cultural roots as well, since it is a pharmacological version of the belief in ‘demon possession’ that has entranced western culture for centuries.”

“Romantic love is an addiction. It’s a very powerfully wonderful addiction when things are going well and perfectly horrible when things are going poorly.”

Let’s believe that we know what a drug is. When you take a drug, there is no consistent outcome. Sure, the pharmacology may result in a similar biological effect. Opioids = analgesia. Amphetamines = energy. However, the perception, experience, meaning and impact are unpredictable. As Zinberg has shown, the drug effect shifts according to:

• Drug (dose, purity, method of use etc.),

• Set (beliefs about the drug, individual vulnerabilities and biology, drug expectation, the current state of mind etc.), and

• Setting (where we take a drug, who we are taking it with, who may be watching us, and even the legal status of the drug).

A person can reach a relatively stable outcome through consistent quality and learning. Still, the next person may have a very different outcome. With a different mind-set, in a different setting, everything can change.

How we define drugs has little to do with pharmacology or with potential harms – it has everything to do with the constructs around the drug. These can change with context. Colonel Peter Demitry described amphetamines as “the gold standard for ‘anti-fatigue.’ We know that fatigue in aviation kills … This is a life-and-death insurance policy that saves lives … This is a common, legal, ethical, moral and correct application” [quoted in War and drugs (Bergen-Cico 2015)]. Yet, in 2006, the United States Attorney General proclaimed methamphetamine to be “the most dangerous drug in America.” The drugs so described are almost identical, and they are currently prescribed to children to treat attention deficit disorder and obesity.

We need to stop thinking of drugs in terms of “harm.” If prohibition were about harm, free climbing would be illegal; paracetamol would require a prescription; alcohol would be banned, and LSD and psilocybin would be readily available. At the wrong dose, in the wrong combination with other drugs, most foods and drugs can cause harm under the wrong circumstances.

So what is this all about? What informs our constructs? As Cohen and others suggest, drug policy is more belief or religion than science. The only U.N. Convention to call something ‘evil’ is the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.  Addiction is described as an evil that must be combated at all costs. The term evil suggests what the real issues are: the mystical experience, the internal resolution of suffering, the feeling of power that challenges church and state. We can feel ‘fine’, but never ‘better’.

Addiction is described as an evil that must be combated at all costs. The term evil suggests what the real issues are: the mystical experience, the internal resolution of suffering, the feeling of power that challenges church and state. We can feel ‘fine’, but never ‘better’.

You cannot point out that, for some people, using an unregulated street drug that will cause certain eventual death may be useful in the moment. The priests of prohibition are horrified and appalled at such a sacrilegious  suggestion. It is unacceptable that a homeless person who is HIV and HEP C positive, is hungry and cold and has no prospects for the future, can inject heroin, using a blunt needle, through the crust of a septic abscess, and instantly find themselves lying simultaneously in the arms their (imagined) mother and lover.

suggestion. It is unacceptable that a homeless person who is HIV and HEP C positive, is hungry and cold and has no prospects for the future, can inject heroin, using a blunt needle, through the crust of a septic abscess, and instantly find themselves lying simultaneously in the arms their (imagined) mother and lover.

We applaud the extreme sportsmen but deplore the pursuit of dopamine through chemical means. The relentless pursuit of money is called determination; the relentless pursuit of comfort through drugs is called “addiction.” We let people suffer the misery of cluster headaches rather  than allow them to find relief in psilocybin. All because they may experience a non-state/church-sanctioned mystical experience. Governments let people suicide from pain, and let people who use unregulated heroin die from fentanyl poisoning while prescribing (the more dangerous) methadone instead. The prohibitionists would rather have someone die “clean” than live “dirty”.

than allow them to find relief in psilocybin. All because they may experience a non-state/church-sanctioned mystical experience. Governments let people suicide from pain, and let people who use unregulated heroin die from fentanyl poisoning while prescribing (the more dangerous) methadone instead. The prohibitionists would rather have someone die “clean” than live “dirty”.

Evolution has ensured that we pursue survival by any means: falling in love, searching for connection, attachment and belonging, and searching for mystical experiences that transcend our mortality. The mechanisms of determination, motivation and “addiction” are all inseparable parts of being human. They are framed as positives until they offend someone’s moral sensibilities or can be used to demonize a particular group.

Once the label of “addict” is used, the prophecy starts to fulfill itself. Most middle-class people who use drugs only develop a serious problem once they get caught using drugs. People keep drug use hidden. To be labelled a user of heroin is a shame few can tolerate. A sex worker becomes a junkie whore to  her colleagues when they discover she uses heroin. We know that if young people use cannabis, the best if not only predictor of future criminality, incarceration and violence is whether or not they get caught. The remedy is worse than the problem.

her colleagues when they discover she uses heroin. We know that if young people use cannabis, the best if not only predictor of future criminality, incarceration and violence is whether or not they get caught. The remedy is worse than the problem.

I admire Carl Hart, whom I consider a friend. He gained his place in academia through one of the few ways a kid from the Ghetto stands a chance of escaping the realities of life as an African American — military service. He became the first tenured African  American Professor of Sciences at Columbia. His research and data turned him into an advocate for developing a better response to problematic drug use. Recently Carl Hart outed himself as someone who uses drugs. No doubt he will feel an immediate backlash. Ultimately, I believe people will pretend he never mentioned his drug use. It is easier to ignore the facts than to confront the accepted “truths” about drugs and addiction.

American Professor of Sciences at Columbia. His research and data turned him into an advocate for developing a better response to problematic drug use. Recently Carl Hart outed himself as someone who uses drugs. No doubt he will feel an immediate backlash. Ultimately, I believe people will pretend he never mentioned his drug use. It is easier to ignore the facts than to confront the accepted “truths” about drugs and addiction.

From grade one, they taught us: there is no such thing as controlled drug use. People who use drugs cannot sustain their work, meaningful relationships or financial commitments. We have to believe that drugs are dangerous, drugs are demons, drugs cause the breakdown of communities, and we must strive for a drug-free world. Later we realize it’s just not true. We should have a fit of righteous anger for being denied coca tea for a mild boost of energy, the joy of MDMA-assisted couples therapy, the mystical experience and the resolution of existential angst through psilocybin. We might also admit that our myths have caused great harm. I mourn the friends who have died inexcusable deaths.

Ultimately there are no good or bad drugs. One person’s poison is someone else’s salvation. In a rational world, there are plants and medicines and molecules that we can use with purpose, informed by knowledge, wisdom and experience, to find comfort, transcendence, temporary relief, joy, belonging and ourselves. In a rational world, there are no drugs at all.

And if there are no drugs at all, what the hell are we treating?

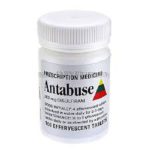

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow.

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow. abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction.

abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction. under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,

under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,  most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year

most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year  in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

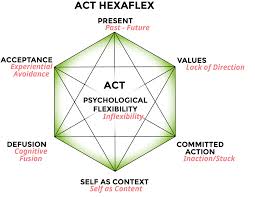

e effective for both groups and individuals, for a wide range of clinical issues, and it allows the clinician to adapt core techniques as needed.

e effective for both groups and individuals, for a wide range of clinical issues, and it allows the clinician to adapt core techniques as needed. Being Present – Staying present in the face of uncomfortable internal or external stimuli, without judgement, can be difficult when coming out of an addiction. Painful thoughts and feelings can return without warning and overwhelm the individual.

Being Present – Staying present in the face of uncomfortable internal or external stimuli, without judgement, can be difficult when coming out of an addiction. Painful thoughts and feelings can return without warning and overwhelm the individual. practiced a mindfulness activity in which she was laying on the ground and watching her thoughts float by like clouds. She simply watched, without judging or avoiding. This gave her the opportunity to see her thoughts as separate from herself, and gave her the space to decide whether to grab the thought or let it pass by.

practiced a mindfulness activity in which she was laying on the ground and watching her thoughts float by like clouds. She simply watched, without judging or avoiding. This gave her the opportunity to see her thoughts as separate from herself, and gave her the space to decide whether to grab the thought or let it pass by. real impact of her addiction: it was pulling her farther away from them. So now, when she would experience a craving in the session, instead of focusing on not drinking, we would choose an image of interacting with her children as a focal point to move towards. Her value acted as a lighthouse that guided her through the craving. She was willing to experience the discomfort of craving because she knew, on the other side of it, her family was waiting, and she wanted that more than she wanted to avoid the discomfort.

real impact of her addiction: it was pulling her farther away from them. So now, when she would experience a craving in the session, instead of focusing on not drinking, we would choose an image of interacting with her children as a focal point to move towards. Her value acted as a lighthouse that guided her through the craving. She was willing to experience the discomfort of craving because she knew, on the other side of it, her family was waiting, and she wanted that more than she wanted to avoid the discomfort.

Though outwardly I was the soul of enthusiastic compliance with my treatment, the questions were brewing. I didn’t think that character defects and self-centeredness had caused my alcohol problems. I had no interest in spending my life confessing my sins to strangers. And I wasn’t convinced that a lifelong abstinence from any mood-altering chemical (except caffeine, sugar and nicotine!) was the only answer.

Though outwardly I was the soul of enthusiastic compliance with my treatment, the questions were brewing. I didn’t think that character defects and self-centeredness had caused my alcohol problems. I had no interest in spending my life confessing my sins to strangers. And I wasn’t convinced that a lifelong abstinence from any mood-altering chemical (except caffeine, sugar and nicotine!) was the only answer. We don’t require anything, other than that members treat each other with respect and not judgement. We support abstinence (a word we prefer over “sobriety,” as “sober” has moral connotations), moderate drinking, and safe drinking.

We don’t require anything, other than that members treat each other with respect and not judgement. We support abstinence (a word we prefer over “sobriety,” as “sober” has moral connotations), moderate drinking, and safe drinking. For me, HAMS has been a critical part of rewriting my identity. The label “alcoholic” seemed to erase everything I had been before, and everything I might be in the future. No matter what I did, even when I didn’t drink, I felt shame. HAMS has taught me that the content of my bloodstream is not the content of my character. Now my identity is not defined by my relationship to alcohol. I am not an “alcoholic.” I am April Wilson Smith.

For me, HAMS has been a critical part of rewriting my identity. The label “alcoholic” seemed to erase everything I had been before, and everything I might be in the future. No matter what I did, even when I didn’t drink, I felt shame. HAMS has taught me that the content of my bloodstream is not the content of my character. Now my identity is not defined by my relationship to alcohol. I am not an “alcoholic.” I am April Wilson Smith. HAMS has just published

HAMS has just published

I read a lot on the internet about whether moderate drinking was possible after a long abstinence. I read the posts on this blog with great interest. I talked through my thought process with my husband, a normal drinker, and he was supportive of my wish to be able to

I read a lot on the internet about whether moderate drinking was possible after a long abstinence. I read the posts on this blog with great interest. I talked through my thought process with my husband, a normal drinker, and he was supportive of my wish to be able to  enjoy a nice glass of wine or good craft beer now and then. This is what I had missed over the years. Those certain occasions when it is so nice to be able to add alcohol to the experience: a fine dinner or a sunny afternoon relaxing on the porch. He was supportive — whether I had a drink or did not, whether I tried it and continued, or tried it and stopped.

enjoy a nice glass of wine or good craft beer now and then. This is what I had missed over the years. Those certain occasions when it is so nice to be able to add alcohol to the experience: a fine dinner or a sunny afternoon relaxing on the porch. He was supportive — whether I had a drink or did not, whether I tried it and continued, or tried it and stopped. Last Saturday night I took the plunge and had one glass of red wine. Waves of fear washed over me. The experience was surreal. Who was I? What was this thing that I was doing? The wine tasted fantastic. I could feel the effect but, amazingly, I did not like it. This was in stark contrast to how I used to experience alcohol, thinking the taste wasn’t too bad and the effect itself was incredibly nice.

Last Saturday night I took the plunge and had one glass of red wine. Waves of fear washed over me. The experience was surreal. Who was I? What was this thing that I was doing? The wine tasted fantastic. I could feel the effect but, amazingly, I did not like it. This was in stark contrast to how I used to experience alcohol, thinking the taste wasn’t too bad and the effect itself was incredibly nice. One week after this experience I can say this. The unleashing of craving from this one drink after 25 years of absolute sobriety was beyond belief. It was like the 25 years had never happened. The portal to a horrible, frightening feeling had been opened. I had the sense of a dual persona hovering at the edges of my life, ready to be activated in full.

One week after this experience I can say this. The unleashing of craving from this one drink after 25 years of absolute sobriety was beyond belief. It was like the 25 years had never happened. The portal to a horrible, frightening feeling had been opened. I had the sense of a dual persona hovering at the edges of my life, ready to be activated in full. In the days that followed that one drink I was gripped with craving and mental obsession about when I could reasonably have another. When I went to work on Monday, to a challenging job that I enjoyed, in my new “maybe a drinker” mindset, the job felt too hard on many subtle but powerful levels. My feelings towards my husband and my children shifted ever so slightly. I felt annoyance at first, and then a more ominous sense that I would not be willing or able to navigate the nuanced ups and downs that are human relationships.

In the days that followed that one drink I was gripped with craving and mental obsession about when I could reasonably have another. When I went to work on Monday, to a challenging job that I enjoyed, in my new “maybe a drinker” mindset, the job felt too hard on many subtle but powerful levels. My feelings towards my husband and my children shifted ever so slightly. I felt annoyance at first, and then a more ominous sense that I would not be willing or able to navigate the nuanced ups and downs that are human relationships. No one would be the wiser if I continued along this path. Outwardly it would look the same. I could force my life to keep going. But there was something really wrong with how it felt, to me, internally, at a deep and vivid

No one would be the wiser if I continued along this path. Outwardly it would look the same. I could force my life to keep going. But there was something really wrong with how it felt, to me, internally, at a deep and vivid  level — that this would be a disastrous path. The degree of effort and struggle that would be introduced into my life would be dreadful. That became obvious — painfully obvious.

level — that this would be a disastrous path. The degree of effort and struggle that would be introduced into my life would be dreadful. That became obvious — painfully obvious.