Now that we are stepping firmly away from politics, I thought I’d end the season with a couple of excerpts from an article I recently published in Aeon. Please go to the publication website for the full essay and links. Otherwise, I’ll present an edited (shortened) version in two installments. Here’s the first:

……….

The view that addiction arises through learning appears to be gathering momentum. In fact the famous “disease model” of addiction remains fully dominant only in the U.S. (It is less prevalent in the UK, Europe, and Australia, though it still has a strong following in the treatment world.) Yet the question remains: if addiction is learned, how does it become so much more crystallised, entrenched, in fact stuck, than other learned behaviours? Given that what we learn we can often unlearn, why is addiction so hard to get rid of?

Johnny was a British plant manager, and his childhood included several years in a boarding school where sexual abuse by clergymen lurked insidiously behind the rustlings of bedtime. Johnny grew up anxious but competent; he married, then divorced, and enjoyed regular visits with his grown children – a relatively normal and predictable life. Until it all unravelled. His friends and business associates found it hard to watch, and impossible to interfere, as Johnny approached end-stage alcoholism. He drank himself so close to death that his first reaction to waking up was surprise. By the final six months, Johnny’s days acquired a strange rhythm. They began with a walk to the fridge, rum and ice already crackling by the time he got to the toilet. They would end 4 to 5 hours later when he crawled to bed on his hands and knees, unable to stand. After a few hours’ sleep, there’d begin another ‘day’ of drinking, which lasted only until his next collapse. Johnny told me he would have committed suicide, but it was happening by itself.

Why was it so hard to overcome this behaviour pattern when it got close to destroying him? Why the horrendous sameness, the insidious stability? Why couldn’t he stop? These are the questions that a learning model of addiction has to answer.

I would call addiction a learned habit. In fact, the word ‘habit’ has been used to describe addiction for ages. Yet habits can be hard to specify. They don’t just show up in behaviour. Racism is a habit that’s invisible until it shows itself in a particular context. I would term addiction a ‘habit of mind’ – a habit of thinking and feeling that sometimes gets expressed in behaviour. But then how can we examine habits that aren’t clearly observable? Let’s look to the brain to find out.

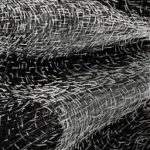

From a neural perspective, habits are patterns of synaptic activation that repeat, when connections among neurons (ie, synapses) fall into the same pattern over different occasions repeatedly. When a  person thinks familiar thoughts or performs familiar actions, a vast number of synapses become activated in predictable – ie, habitual – configurations. Patterns of neural firing in one region become synchronised with patterns of firing in other regions, and that helps the participating synapses form these habitual connections.

person thinks familiar thoughts or performs familiar actions, a vast number of synapses become activated in predictable – ie, habitual – configurations. Patterns of neural firing in one region become synchronised with patterns of firing in other regions, and that helps the participating synapses form these habitual connections.

With each repetition, activated synapses become reinforced or strengthened, and alternative (less used) synapses become weakened or pruned. Meanwhile, active synapses give rise to the activation of other  synapses with which they’re connected, and because connections between brain cells are almost always reciprocal (two-way), the reinforcing activation is returned. Thus, repeated patterns of neural activation are self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing: they form circuits or pathways with an increasing probability of ‘lighting up’ whenever certain cues or stimuli (or thoughts or memories) are encountered. According to Hebb’s rule: ‘Cells that fire together, wire together.’

synapses with which they’re connected, and because connections between brain cells are almost always reciprocal (two-way), the reinforcing activation is returned. Thus, repeated patterns of neural activation are self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing: they form circuits or pathways with an increasing probability of ‘lighting up’ whenever certain cues or stimuli (or thoughts or memories) are encountered. According to Hebb’s rule: ‘Cells that fire together, wire together.’

In this way, the brain exemplifies the way all living systems evolve and stabilise. All living systems, from organisms to societies, ecosystems to brains, are complex systems with emergent properties. That means that their structure, their shape, emerges from the interaction of many components that change each other over time. In other words, these systems self-organise due to recurrent interactions (feedback loops) among their elements.

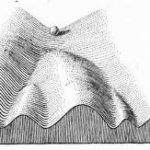

It so happens that there is a robust scientific language for understanding habit-formation in self-organising systems, centred on the term ‘attractor’. An attractor is simply a stable state, which can emerge for a while in a complex (e.g., living) system. So: seeds grow into trees and then stabilise to an  attractor: the tree acquires a shape. Birds fly in sync with each other and form a V-shaped (or other-shaped) flock. Ecosystems go through periods of massive change (eg, speciation and species death) and then stabilise. Cities stabilise. Cultures stabilise. Even family dynamics stabilise. Family arguments inevitably fall back into the same infuriating script.

attractor: the tree acquires a shape. Birds fly in sync with each other and form a V-shaped (or other-shaped) flock. Ecosystems go through periods of massive change (eg, speciation and species death) and then stabilise. Cities stabilise. Cultures stabilise. Even family dynamics stabilise. Family arguments inevitably fall back into the same infuriating script.

Complex systems are composed of elements such as individuals in a society or ecosystem, or cells in an organ or organism. These elements continue to interact – they cause changes in each other, which cause further changes in each other, and so forth – until they arrive at stable states, at least for a while.

So what’s the point of a word like ‘attractor?’ Complex systems such as us and our brains reach stability in a very different way than cars or billiard balls (nonliving systems). They have not lost their energy; they continue to grow and develop, to live. But for some period of time, the feedback loops that comprise them provide steadiness or balance, like your body temperature after you’ve gotten used to a blast of wintry air. At that point, we can say that the system has reached its attractor. Its components now interact in a way we might call a temporary equilibrium.

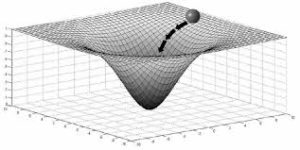

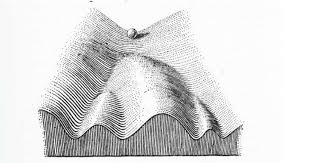

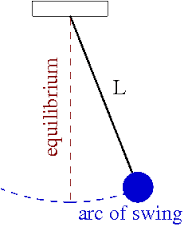

The attractor idea is tremendously useful for describing the development of human habits, because human habits settle into place; they are not programmed by our genes or determined by the environment. But how exactly do attractors form in growing systems, why do they form, and why do they hold the  system in place? Attractors are often portrayed as valleys or wells on a flat surface, that surface representing many possible states for the system to occupy. The system, the person, can then be seen as a marble rolling around on this surface of possibilities until it rolls into an attractor well. And then it’s hard for it to roll back out. Physicists will say that the system requires extra energy to push itself out of its attractor. The analogy in human development might be the effort people require to shift out of a particular pattern of thinking or acting.

system in place? Attractors are often portrayed as valleys or wells on a flat surface, that surface representing many possible states for the system to occupy. The system, the person, can then be seen as a marble rolling around on this surface of possibilities until it rolls into an attractor well. And then it’s hard for it to roll back out. Physicists will say that the system requires extra energy to push itself out of its attractor. The analogy in human development might be the effort people require to shift out of a particular pattern of thinking or acting.

In human development, normative achievements can be seen as attractors. These might include learning to be a competent language user, or falling in love and having kids. But individual personality development can also be described in terms of attractors – recognisable features that characterise the individual in a particular way. And these features can be seen to branch out with development and form ruts — ruts that can remain in place for a long time.

In human development, normative achievements can be seen as attractors. These might include learning to be a competent language user, or falling in love and having kids. But individual personality development can also be described in terms of attractors – recognisable features that characterise the individual in a particular way. And these features can be seen to branch out with development and form ruts — ruts that can remain in place for a long time.

Addiction is just such an attractor. The staying power of addiction doesn’t derive from a good fit with the social world or the playing out of some innate human tendency. Addiction involves an intense relationship between a person and a substance or behaviour. That relationship is itself a feedback loop that has reached the stage of self-reinforcement, and it is interconnected with other feedback loops that facilitate the addictive pattern. These feedback loops have driven the system – the person, the person’s brain – into an attractor that deepens over time.

…THE REST TO COME IN A COUPLE OF DAYS…

The participants in the study were cancer patients (understandably) experiencing lots of anxiety and depression about their illness. To quote from the

The participants in the study were cancer patients (understandably) experiencing lots of anxiety and depression about their illness. To quote from the  trips, scary psychotic detours that may last hours or even weeks. But for most people, at least those willing to let go of their day-to-day constructions of reality (for a while), I think psychedelics can be a real boon. They can take us on a journey that reveals a universe we may not have known existed. Kinda like the explorers of the 1400s and 1500s who sailed past the horizon and discovered that the world was round, not flat. (If interested,

trips, scary psychotic detours that may last hours or even weeks. But for most people, at least those willing to let go of their day-to-day constructions of reality (for a while), I think psychedelics can be a real boon. They can take us on a journey that reveals a universe we may not have known existed. Kinda like the explorers of the 1400s and 1500s who sailed past the horizon and discovered that the world was round, not flat. (If interested,  The brain is divided into several functional networks, each responsible for a different kind of engagement with the world. A network connecting prefrontal (and other regions) is in charge of problem solving, something we do a lot. A network anchored in the parietal cortex (that big middle part) is responsible for shifting attention to incoming stimuli, events that are potentially important in the here-and-now. But the default mode network is a set of cross-linked regions that extend from the middle of the frontal lobes (social cognition) to the hippocampus, which keeps track of the details of memory, to parts of the cingulate cortex involved in compacting memories into a gist-like overview, to areas in the posterior cortex that underlie our perception of other people’s motives and feelings.

The brain is divided into several functional networks, each responsible for a different kind of engagement with the world. A network connecting prefrontal (and other regions) is in charge of problem solving, something we do a lot. A network anchored in the parietal cortex (that big middle part) is responsible for shifting attention to incoming stimuli, events that are potentially important in the here-and-now. But the default mode network is a set of cross-linked regions that extend from the middle of the frontal lobes (social cognition) to the hippocampus, which keeps track of the details of memory, to parts of the cingulate cortex involved in compacting memories into a gist-like overview, to areas in the posterior cortex that underlie our perception of other people’s motives and feelings. CV…I wonder what’s for dinner tonight…am I supposed to cook, or is it Isabel’s turn? The DMN network is what manufactures all those wandering thoughts and fantasies. (And note that more advanced meditators show less activation of the DMN.) So the purpose of the network seems to be to propagate the sense of a coherent self, an ego, a me. And the problem with that is that ALL of our worries, negative thoughts, concerns about how meaningless it all is, concerns about whether I’m going to get sick, die, be lonely, or get high, relapse, and how long that might go on…all that fussing is simply a cascade of revisions of how best to care for oneself, protecting, optimizing, enhancing…ME!

CV…I wonder what’s for dinner tonight…am I supposed to cook, or is it Isabel’s turn? The DMN network is what manufactures all those wandering thoughts and fantasies. (And note that more advanced meditators show less activation of the DMN.) So the purpose of the network seems to be to propagate the sense of a coherent self, an ego, a me. And the problem with that is that ALL of our worries, negative thoughts, concerns about how meaningless it all is, concerns about whether I’m going to get sick, die, be lonely, or get high, relapse, and how long that might go on…all that fussing is simply a cascade of revisions of how best to care for oneself, protecting, optimizing, enhancing…ME! Psychedelics release us from a preoccupation with ourselves by reducing DMN activation. They allow us to be more open, more connected with other people, with our planet, with our universe. Psychedelics can usher us through a Copernican shift from viewing ourselves as the centre of the universe to viewing ourselves as interested participants in something much larger and possibly much more interesting.

Psychedelics release us from a preoccupation with ourselves by reducing DMN activation. They allow us to be more open, more connected with other people, with our planet, with our universe. Psychedelics can usher us through a Copernican shift from viewing ourselves as the centre of the universe to viewing ourselves as interested participants in something much larger and possibly much more interesting.

I’ll spare you all the usual listing of what’s wrong in the world, from Brexit, to the right-wing populist movements sweeping Europe, to Trump. Well I guess I didn’t spare you. But for me what it comes down to with Trump is pretty simple. He’s a liar and a cheat. Almost everything he says is a lie. He replaces it the following week or the following day — usually with another lie. And most of his campaign promises were mere strategic gambits to win votes. He’s not going to build a wall, or prosecute Hillary. Who ever imagined that he would? He’s even talking about taking a serious look at climate change and maybe endorsing the Paris Accord, which is of course good news. It’s just a shame that he got voted in on his promise to ignore the environment because climate change is a fantasy promoted by the Chinese.

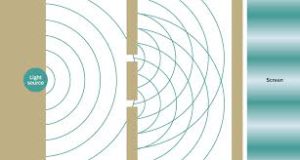

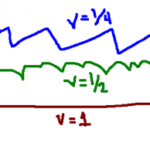

I’ll spare you all the usual listing of what’s wrong in the world, from Brexit, to the right-wing populist movements sweeping Europe, to Trump. Well I guess I didn’t spare you. But for me what it comes down to with Trump is pretty simple. He’s a liar and a cheat. Almost everything he says is a lie. He replaces it the following week or the following day — usually with another lie. And most of his campaign promises were mere strategic gambits to win votes. He’s not going to build a wall, or prosecute Hillary. Who ever imagined that he would? He’s even talking about taking a serious look at climate change and maybe endorsing the Paris Accord, which is of course good news. It’s just a shame that he got voted in on his promise to ignore the environment because climate change is a fantasy promoted by the Chinese. If there’s anything useful I can say at the moment, it’s to suggest we look at the present glut of bad news as waves rather than particles. Sounds spiffy to use quantum terms. Waves seem like tendencies, currents, gusts…in a universe that is constantly in flux. Whereas particles…give the sense of matter, substance, stuff

If there’s anything useful I can say at the moment, it’s to suggest we look at the present glut of bad news as waves rather than particles. Sounds spiffy to use quantum terms. Waves seem like tendencies, currents, gusts…in a universe that is constantly in flux. Whereas particles…give the sense of matter, substance, stuff  that collects in corners until there’s so much of it you really have to rent heavy machinery to get rid of it. So when the Buddha talked about impermanence as the main act, maybe he was thinking more in terms of waves than particles. Impermanence actually seems like good news at the moment.

that collects in corners until there’s so much of it you really have to rent heavy machinery to get rid of it. So when the Buddha talked about impermanence as the main act, maybe he was thinking more in terms of waves than particles. Impermanence actually seems like good news at the moment. I sometimes wonder what’s at the core of all these right-wing leanings. Let’s preserve what we’ve got. Let’s keep America American. Let’s maintain our way of life because it’s being threatened. Damn right your way of life is being threatened because….get ready…you’re going to die! What could be more threatening to anyone’s way of life?

I sometimes wonder what’s at the core of all these right-wing leanings. Let’s preserve what we’ve got. Let’s keep America American. Let’s maintain our way of life because it’s being threatened. Damn right your way of life is being threatened because….get ready…you’re going to die! What could be more threatening to anyone’s way of life? breathing steam, I think: this is just fine. This is a great moment. This wish to preserve things the way they’ve always been (as if that were a good thing)… What’s the point of that?

breathing steam, I think: this is just fine. This is a great moment. This wish to preserve things the way they’ve always been (as if that were a good thing)… What’s the point of that?

policies over the last many years: opposition to raising the minimum wage, opposition to universal health care, guns for all, reduced taxation on the wealthy, training people to blame others for their misfortunes rather than look at the elephant (pun intended) in the room.

policies over the last many years: opposition to raising the minimum wage, opposition to universal health care, guns for all, reduced taxation on the wealthy, training people to blame others for their misfortunes rather than look at the elephant (pun intended) in the room. something strong, powered by defiance. Consequences be damned. It’s sort of the ultimate “fuck you” directed at…well directed at the adults upstairs….Obama, Hillary….the adults who seem somehow to be responsible for whatever pain we’re feeling.

something strong, powered by defiance. Consequences be damned. It’s sort of the ultimate “fuck you” directed at…well directed at the adults upstairs….Obama, Hillary….the adults who seem somehow to be responsible for whatever pain we’re feeling. Sometimes a sick system needs a chance to swing all the way wrong before the pendulum reverses its direction. Maybe with a Republican president and Congress, legislation, policy, the courts will have had a full run, their unfettered chance to make things as wrong as possible — and then things will swing back leftward. Because there won’t be anyone to blame and because the politics of selfishness and fear are unstable — they can’t last indefinitely.

Sometimes a sick system needs a chance to swing all the way wrong before the pendulum reverses its direction. Maybe with a Republican president and Congress, legislation, policy, the courts will have had a full run, their unfettered chance to make things as wrong as possible — and then things will swing back leftward. Because there won’t be anyone to blame and because the politics of selfishness and fear are unstable — they can’t last indefinitely.

corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible.

corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible. What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,

What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,  programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits.

programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits. zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see

zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see  previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively.

previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively. If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video

If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video  games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has

games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has  Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets

Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets  of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they

of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they  also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition.

also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition. So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?

So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?