Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open!

Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open!

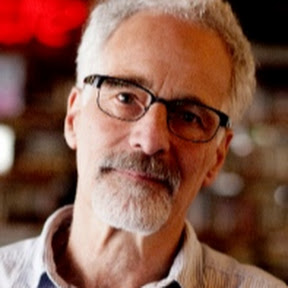

In my last scientific article on addiction and recovery, I set out a new and improved model of addiction (described in more detail here). I looked at addiction as a “narrowing” of the brain — a setting and solidification of neural networks focused on drug rewards — paralleled by a narrowing of the (available, meaningful) social environment.

This is not rocket science, or even brain science.

The main trouble with the “brain disease model” of addiction is that it ignores the massive impacts of the social environment. Yet we know that emotional challenges create the predisposition to later addiction. We know that the social environment (including one’s family history) matters hugely. We know that abuse (including emotional abuse) and neglect during our growing-up years are by far the best predictors of addiction in adulthood. The brain disease model simply can’t make sense of these facts. How could a brain disease develop from hard times growing up?

So in my model I emphasize that harmful social experiences have a shrinking or narrowing effect. If caregivers or peers make you feel off or wrong or insecure, or unable to trust, unable to just be, then you ingest what gives you the next best thing. Something that  soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain.

soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain.

The social shutdown isn’t just in the words and deeds you receive from people you know. It’s also a reduction in the places you go, activities, walks in the park, the freedom to be buffeted by babbling crowds shopping, living, watching, listening. When drink or drugs seem all that’s available to provide what you need, you let go of other possible sources of pleasure and satisfaction, energy, and identity. They were never that reliable to begin with. And before long you forget about them, you forget how to find them, you forget they even exist. That’s what locks addiction in place.

It’s what Johann Hari wrote about in Chasing the Scream: the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety; it’s connection.

So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile.

So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile.

Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems.

Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems.

For those who are taking care of kids who are also stuck at home, the increased contraction of possibilities is laced with stress. You have to attend to these little buggers all day long. You love them,  okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not

okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not  only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect.

only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect.

So here’s what you should do. If you’re trying to quit or control substance use (or other addictive activities — porn, online gambling, whatever), get your ass out of the house! Social distancing doesn’t mean solitary confinement. Here in my city in the Netherlands, I’ve seen more and more people strolling over the last two or three weeks. People walk, and when they’re about to pass by, either they or you or most likely both of you move aside, so there’s a good two meters (six feet) separation. That separation doesn’t prevent, in fact it seems to enhance, people’s tendency to smile at each other, say Hi, wave, even utter a few words of greeting.

And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask

And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask  about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

Getting out of your home is going to make you feel like you’re a part of the world rather than a prisoner on Rikers Island. And that’s going to help you feel like you don’t need to get loaded, or maybe have two drinks instead of eight, or maybe watch a movie, read a book, and fall asleep gently, wondering about the mysterious mix of chance and destiny that’s landed us in this crazy time. Together.

………………………..

If you haven’t yet, please visit and maybe subscribe to my YouTube channel. It’s new, and it features videos of my talks and interviews over the past few years. No spam or junkmail of any kind, I promise.

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of  the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be?

the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be? reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later.

reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later. how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease.

how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease. that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated.

that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated. The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes.

The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes. Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else.

Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else. of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in

of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in  your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction.

your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction. People, please please click on

People, please please click on

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see.

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see. LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “

LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “ the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

genius. He was the first (as far as I know) to develop a “talking cure” for serious emotional difficulties, and he was the first to bring the idea of unconscious wishes and motives into public parlance. Sure,

genius. He was the first (as far as I know) to develop a “talking cure” for serious emotional difficulties, and he was the first to bring the idea of unconscious wishes and motives into public parlance. Sure,  psychoanalysis — on the couch, four times a week, for fifteen years (?!) — hasn’t lived up to expectations, and I believe it’s correctly pushed aside by more focused, present-tense-oriented, and evidence-based treatment models.

psychoanalysis — on the couch, four times a week, for fifteen years (?!) — hasn’t lived up to expectations, and I believe it’s correctly pushed aside by more focused, present-tense-oriented, and evidence-based treatment models. with a capital S is to be our lodestone, then psychoanalysis doesn’t look so hot either. But, okay, Dodes is inspiring, he’s developed his methods over decades, he’s come

with a capital S is to be our lodestone, then psychoanalysis doesn’t look so hot either. But, okay, Dodes is inspiring, he’s developed his methods over decades, he’s come  problems in the light of one’s early development. A realistic and increasingly popular spin-off of this position is the emphasis on childhood trauma, most famously highlighted by

problems in the light of one’s early development. A realistic and increasingly popular spin-off of this position is the emphasis on childhood trauma, most famously highlighted by  There are addiction treatment centres (e.g.,

There are addiction treatment centres (e.g.,  offers a harm-reduction approach that has psychodynamic psychology (and thus individual psychotherapy) built into it. I particularly like Tatarsky’s model (I spoke there and met him last June) because it is fundamentally empathic and humanistic, honouring individual differences and working with them.

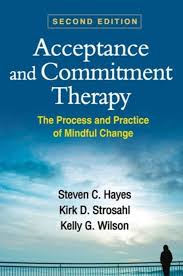

offers a harm-reduction approach that has psychodynamic psychology (and thus individual psychotherapy) built into it. I particularly like Tatarsky’s model (I spoke there and met him last June) because it is fundamentally empathic and humanistic, honouring individual differences and working with them. What’s most interesting to me is how psychodynamic ideas provide a foundation underlying many current schools of psychotherapy. With respect to addiction, ACT and IFS (my favourites — see last post) are all about bringing the past into the present and dealing with it. What seems to be missing from our lives? When did that start? Where does the depression come from? What messages do we repeatedly give ourselves that make us feel hopeless or despicable, so there seems little opportunity for relief except our addiction? Where do contradictory self-statements, like yes, this is what I want and I hate doing this! actually come from?

What’s most interesting to me is how psychodynamic ideas provide a foundation underlying many current schools of psychotherapy. With respect to addiction, ACT and IFS (my favourites — see last post) are all about bringing the past into the present and dealing with it. What seems to be missing from our lives? When did that start? Where does the depression come from? What messages do we repeatedly give ourselves that make us feel hopeless or despicable, so there seems little opportunity for relief except our addiction? Where do contradictory self-statements, like yes, this is what I want and I hate doing this! actually come from? psychotherapists do, is blend different approaches, revising and refining our methods until we find what works best. And what works best appears at the interface of our own personality and knowledge base, our style of connecting with others, and the particular problems (in my case, mostly addiction) that come our way.

psychotherapists do, is blend different approaches, revising and refining our methods until we find what works best. And what works best appears at the interface of our own personality and knowledge base, our style of connecting with others, and the particular problems (in my case, mostly addiction) that come our way.

themselves, sometimes despite vast challenges (including abuse of one kind or another) during childhood and/or adolescence. And I’ve helped people devise cognitive tricks to shunt their trajectory away from substance use and toward more satisfying habits.

themselves, sometimes despite vast challenges (including abuse of one kind or another) during childhood and/or adolescence. And I’ve helped people devise cognitive tricks to shunt their trajectory away from substance use and toward more satisfying habits. But there seems to be a black hole in the centre of the addiction galaxy that sucks in techniques of every sort and laughingly squishes them to nothing, tosses them back down some wormhole to some parallel universe. And surely that’s because addiction boils down to a unique “thing” which is totally psychological, totally biological, and totally social. A habit in the workings of our cells, our minds, and our interpersonal relations.

But there seems to be a black hole in the centre of the addiction galaxy that sucks in techniques of every sort and laughingly squishes them to nothing, tosses them back down some wormhole to some parallel universe. And surely that’s because addiction boils down to a unique “thing” which is totally psychological, totally biological, and totally social. A habit in the workings of our cells, our minds, and our interpersonal relations. later) you’re often left with an aching emptiness. And what the hell are we humans supposed to do with that?! (Mindfulness/meditation has some answers, but let’s face it, the solution isn’t obvious.)

later) you’re often left with an aching emptiness. And what the hell are we humans supposed to do with that?! (Mindfulness/meditation has some answers, but let’s face it, the solution isn’t obvious.)

IFS

IFS