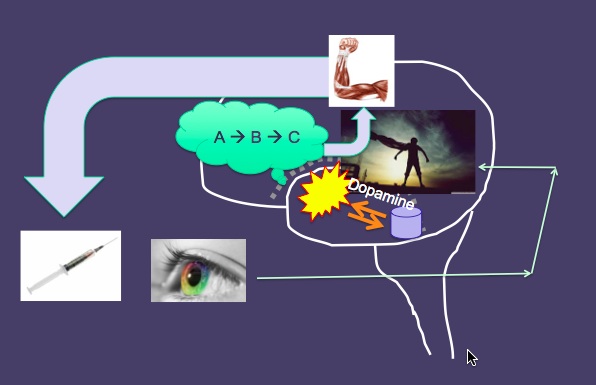

I want to start unraveling the talks I heard, beginning with Kent Berridge’s talk. If you haven’t been following this blog or read my book, here’s some background: Berridge has made two major contributions to the study of addiction. The first is the idea that “wanting” and “liking” are independent neural systems. Wanting (or craving, as we understand it in addiction) is mostly fueled by dopamine, which is sent from the midbrain to the nucleus accumbens (NACC; or ventral striatum), a major center for goal-directed pursuit, lying in the middle of the brain, deep within the cortex and surrounded by the limbic structures. Here’s that slide once again. The NACC is represented by that yellow explosion, to convey the growth of craving over a matter of seconds or minutes. On the other hand, liking (or pleasure) is provided by — guess what? — opioids, whether they come from your local dealer or from the natural processes of your own brain (the hypothalamus produces opioids, which are critical for calming us down and relieving pain). The idea that wanting and liking are truly dissociable is pretty radical, both in psychology and in neuroscience. In the present post, I want to tell you about Kent’s recent research, as reported in Boston two weeks ago, where he demonstrates this independence — in that pristine way scientists have of breaking things down to  their fundamental components.

their fundamental components.

Berridge’s other main contribution is the idea of incentive sensitization. This is the notion that particular cues or stimuli (whether out there in the world or generated from our own fantasies, memories, daydreams, etc) become strongly associated with our drug or drink of choice. And those cues — all by themselves — activate the wanting circuit. They directly release dopamine to the NACC, so that we find ourselves suddenly beset by craving, simply by exposure to a cue. The strength of that incentive sensitization obviously increases the more often we use, because the experience itself serves to reinforce the association with the cue. But I won’t discuss this further for now.

Okay, so Kent gets up in front of this group of 15 or so people, including only two other neuro people (Davidson and me). And he’s explaining his recent research with rats, in which he’s set out to show that wanting and liking truly are separate systems. He wants to get his message across to the group, of course, but the main goal is to develop a talk that will be of interest to you-know-who. He wants, we want, the Dalai Lama to say: Hey that’s really cool! Now I get how you can want something without even liking it! For Kent, and for me, this issue gets to the heart of the problem of desire — a problem which is as central to Buddhist psychology as it is to addiction psychology.

So here’s the experiment: The rat is “trained” to press a lever that delivers a sweet solution. This is a very typical “Skinnerian” learning paradigm. Rats love sweetness — don’t we all? — and it’s been shown that sugar speaks directly to those opioid-fueled cells in the NACC. So here’s a rat that has experienced liking which has led to wanting, in the very natural way that we are “trained” to go after rewarding experiences in life. So they are willing to press the lever many times over, as motivated by their wanting for the sweet taste — and as shown, through other studies, to depend on the flow of dopamine following that initial opioid rush.

So here’s the experiment: The rat is “trained” to press a lever that delivers a sweet solution. This is a very typical “Skinnerian” learning paradigm. Rats love sweetness — don’t we all? — and it’s been shown that sugar speaks directly to those opioid-fueled cells in the NACC. So here’s a rat that has experienced liking which has led to wanting, in the very natural way that we are “trained” to go after rewarding experiences in life. So they are willing to press the lever many times over, as motivated by their wanting for the sweet taste — and as shown, through other studies, to depend on the flow of dopamine following that initial opioid rush.

But there’s another lever in the cage. When the rat presses it, just in the process of exploring its environment, it delivers a very salty taste. Kent is sitting in front of his computer, at the end of the table near the screen, and he looks up at us, wanting to get across how very nasty this liquid tastes to the poor rat. Imagine the taste of sea water, he says. Now imagine something that’s at least 10 times saltier — beyond the level of the Dead Sea. And I feel like I’m glimpsing the soul of this scientist. He is right there in the minds of his rats, trying to imagine — and communicate — what they are experiencing. Because that’s the necessary link here. The connection between experience and behavior. And if you’re studying it in rats rather than humans, you’d better be able to imagine what it’s like to be a rat. Anyway, the rats don’t need another trial to learn to stay away from lever #2. They hate what it gives them. There is no pleasure to be had there.

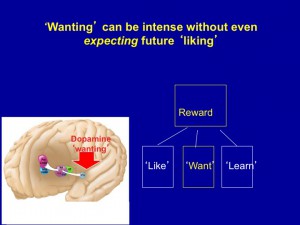

Now here comes the essence of being a good scientist: being clever enough to find the fracture point where you can split a phenomenon into its parts. We’ve got liking and wanting for lever #1. And zero liking or wanting for lever #2. Then the experimenter gives the rat a drug that reduces their blood level of sodium  way below normal. They become salt-deprived. And now the punchline: The rats immediately go to lever #2 and start pressing like hell. Kent and his assistants have completely bypassed liking to get to wanting. There is clearly a high degree of wanting present, but there was never — not even once — an experience of liking that led to it.

way below normal. They become salt-deprived. And now the punchline: The rats immediately go to lever #2 and start pressing like hell. Kent and his assistants have completely bypassed liking to get to wanting. There is clearly a high degree of wanting present, but there was never — not even once — an experience of liking that led to it.

Half the people in the room didn’t get it at all. So…the rats were salt-deprived. So they went after the salt lever? So what? Kent read their blank expressions and tried his best to convey what was so cool here. I sensed his disappointment. Who wants to go to all that trouble and have the punchline fall flat? The rats didn’t know they were salt-deprived, he explained. But the wanting circuit was immediately activated by something, some change in their biological state. It doesn’t really matter what activated it. The point is, wanting does not have to arise from liking. It’s an independent process, in mind and brain. It can arise from anything!

For me, the parallels with addiction were immediately striking. That sudden wanting, craving, compulsion that we experience for our drug of choice doesn’t have to depend on how much we liked it in the past — either the distant past or the recent past. You can crave something that you’ve never liked — just because, at some level, you need it. Granted, with drugs and booze, there is usually pleasure the first many times, then the pleasure fades, and after awhile there is no pleasure. Not even the anticipation of pleasure. The wanting comes from needing it, not from liking it. (Mind you, with tobacco, it seems you never have to experience any pleasure to graduate to craving.) So addiction is sort of like the rat experiment with a hunk of time subtracted out. After we become addicted, wanting has nothing to do with how much we do or did like it.

Following some questions and discussion, I think most of the group got it. You had to go right into Kent’s world — the world of a scientist as clever as he is determined. The point wasn’t what caused the sudden wanting. The point was simply that wanting and liking can be shown to be totally independent processes. Will the Dalai Lama get it? Will it help him, and the rest of us, understand something crucial about addiction?

Let’s hope so.

Leave a Reply