…by Judge Allison Krehbiel with Marc Lewis…

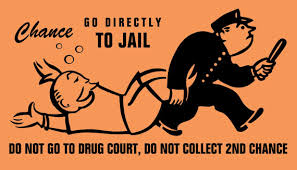

I (Marc) was in Minnesota last fall, invited to speak at a conference on addiction to a large university audience. I met many fascinating people during my visit, but the most memorable moment was an unexpected tour of the trenches where the War on Drugs is still being fought, day by day, and perhaps gradually replaced by a more optimistic response to addiction.

Through the mediation of my hosts, the judge who presided at the local drug court invited me to come and observe. And despite my distaste for the legal system, I figured that as an “addiction expert” I was obligated to see what went on. I had only the vaguest idea of what a drug court was — some creepy hybrid of the American justice system, disguised as a generous compromise for  addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black.

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black.

All rise! We did, and so did my pulse. The last time I’d sat in court I was next to my own lawyer, waiting for sentencing. Judge Krehbiel radiated steely purpose and total authority. I had to remind myself I wasn’t the one on trial. And I began to recognize the druggies, the accused, the probationers and those awaiting sentencing, the jobless meth addicts interspersed among friends and family members in the front rows. I sat down in the back, breathing again, unchallenged, undisturbed. And my expectations began to crumble.

The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride.

The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride.

But could this visit to the border region of criminal culpability actually work for these people? Was there an exit door? Or was the whole thing a ruse, a delay that would last until one false move sent them to jail?

Here’s what Judge Krehbiel has to say about what goes on in her court:

……………………………………

I’ve been a judge for fourteen years, and for ten of those years, I’ve presided over drug court. Of course, all of the drug court participants find my drug court while passing through the criminal justice system and to many outsiders, drug courts seem to “coerce” recovery. I don’t see it that way.

Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

The success of the participants is largely dependent on the quality of the drug court and the attitude of the judge. In my view “compassionate coercion” is essential. My task is to help rather than punish. Yet judges must also realize that, though we may be learned in the law, few of us also hold medical degrees. We function as part of a team.

As the “drugs of choice” (a “choice” that is heavily influenced by street availability) change, so do expert opinions on how best to treat individuals suffering from addiction. For example, the recent increase in opiate addiction (and with it, the return of heroin) caused much discussion among drug court professionals as to whether medically assisted recovery is really recovery at all. I’ve not yet come to a conclusion as to the issue. However, there are a few things about which I am certain.

First, medical providers and appropriate drug court professionals must be able to freely converse regarding patients/participants. The prescribing doctor needs to know exactly what the court expects of his or her patient and the drug court professional needs to know exactly what the doctor requires. In my experience and on more than one occasion, methadone prescribed to one participant was used by another participant. Medical professionals untrained in addiction don’t catch such infractions — probation agents do. Second, judges and other court professionals have to accept that there are widely diverse paths to recovery, many of which deviate from a criminal justice approach. Although ninety meetings in ninety days might work for a life-long alcoholic, Xyprexa might be the better bet for an opiate addict. [Note: Judge Krehbiel corrected this text on 20 May, after her mistake was pointed out by readers: She says she meant Suboxone (buprenorphine), not Xyprexa — an error that actually underscores her frank admission that she’s no doctor!] In fact, in states where marijuana is legal, it might be prescribed to ease the agony of opiate withdrawal. In short, we must be curiously open to advances in the treatment of our chemically dependent clientele. We have to look beyond the justice system and recognize the personal, social, and medical factors that interact to shape their lives.

As I stated earlier, I don’t have a degree in medicine and therefore, I cannot, nor should any other judge, dictate whether or not a drug court participant is prohibited from taking prescription medication. However, I can compassionately coerce that participant to sign a release of information that allows a probation agent and treatment provider to share information with the prescriber of that medication. If the issue is pain, is there a non-addictive alternative to Vicodin? If the issue is anxiety, is there a non-addictive alternative to Valium? These questions can only be answered if there is open communication amongst all the professionals engaged in recovery assistance.

The goal we all aim for is the same: allowing people to reach their full potential and live a life outside the restraints of addiction.

Hon. Allison L Krehbiel

Fifth Judicial District Court

P.S. I know that this is a contentious approach to addiction “treatment.” But my goal here is to put a lot of different approaches on the table, reflecting the range of what’s out there. Also, having met Allison and chatted with her after the court proceedings, I can attest to her sincerity, dedication, and concern for her participants’ welfare, whether or not one agrees with her views.

I’d like to hear what you guys think.

Leave a Reply