A 30% increase in overdose deaths in 2020? Sure, the year of the pandemic. Most agree that isolation has been a huge causal factor, but what does isolation mean in a world patched together by social media? Rat Park and Social Baseline Theory help us see the full picture.

Over the last few months there have been numerous reports of a sharp rise in overdose deaths in 2020. Most recently (last month) the National Center for Health Statistics reported an increase of 21,000 (almost 30%) — totaling 93,000 deaths in one year. Virtually all experts associate this increase with the pandemic. Many reasons are aired: stretched health-care facilities, less access to naloxone, less access to doctors, housing issues, and…increased isolation.

Over the last few months there have been numerous reports of a sharp rise in overdose deaths in 2020. Most recently (last month) the National Center for Health Statistics reported an increase of 21,000 (almost 30%) — totaling 93,000 deaths in one year. Virtually all experts associate this increase with the pandemic. Many reasons are aired: stretched health-care facilities, less access to naloxone, less access to doctors, housing issues, and…increased isolation.

The experts agree that isolation’s been a major concern. Yet our understanding of the nature of isolation is superficial. Since almost everyone has been on social media this year, madly zooming away the hours, what does it actually mean to be alone, physically, bodily, especially for people living alone, each in their own little box?

The experts agree that isolation’s been a major concern. Yet our understanding of the nature of isolation is superficial. Since almost everyone has been on social media this year, madly zooming away the hours, what does it actually mean to be alone, physically, bodily, especially for people living alone, each in their own little box?

We know that isolation makes people more vulnerable to depression. Loneliness = depression. And depression is the gateway to more extreme drug use. But while living in states of lockdown, we’ve spent the year zooming, texting, chatting, tweeting, emailing, Whatsapping, posting to Instagram, following on Facebook… Don’t these explicitly social activities dispel isolation and defeat loneliness? It certainly helps to connect with people any way we can. But flat screens have their limits. They don’t allow for the spontaneity and ease, the free flow of real conversation, the richness of body language, the way people position themselves, move their heads, their feet, their eyes, when they’re actually, physically together. Never mind pheromones and oxytocin — the good odours that humans exude. So…some degree of closeness must remain out of reach. Maybe a large degree.

What kind of closeness do we humans need in order to feel connected, supported, safe — and free of addiction? Two research programs 30 years apart tell the story.

The first is Rat Park. Most of you are familiar with Bruce Alexander’s research in the 70s and 80s, memorialized in the addiction world as “Rat Park.” These studies showed that isolated rats (kept alone in their cages) chose to drink water laced with drugs like morphine, while those allowed to socialize, cuddle, and have sex in a park-like (for rats) environment avoided the drug solution and drank plain water instead. There are

The first is Rat Park. Most of you are familiar with Bruce Alexander’s research in the 70s and 80s, memorialized in the addiction world as “Rat Park.” These studies showed that isolated rats (kept alone in their cages) chose to drink water laced with drugs like morphine, while those allowed to socialize, cuddle, and have sex in a park-like (for rats) environment avoided the drug solution and drank plain water instead. There are  thousands of references to Rat Park online (e.g., here), and Alexander’s own site summarizes the findings and extends them with a whole philosophy on what drives addiction. One of Alexander’s reflections captures the main lesson: “Solitary confinement drives people crazy; if prisoners in solitary have the chance to take mind-numbing drugs, they do.”

thousands of references to Rat Park online (e.g., here), and Alexander’s own site summarizes the findings and extends them with a whole philosophy on what drives addiction. One of Alexander’s reflections captures the main lesson: “Solitary confinement drives people crazy; if prisoners in solitary have the chance to take mind-numbing drugs, they do.”

But does verbal communication alleviate the damage done by solitary housing? Rats aren’t verbal. When they socialize, they cuddle, play, lick, fondle and fuck. We’re mammals too. How much does verbal communication satisfy our needs?

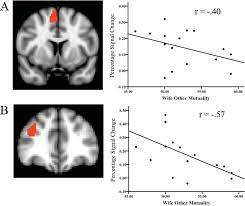

The second research program has come to be known as Social Baseline Theory (SBT). Starting in 2006, James Coan and colleagues studied the effects of hand-holding on the activation of brain structures responsible for coping with stress.  Subjects inside a brain scanner (fMRI) held hands with either a marital partner, a friend, or a stranger positioned outside the scanner. When exposed to (mild) electrical shocks (psychologists’ favourite way to induce stress) these brain structures showed less activation (they were less “aroused”) when the subject was able to hold hands, even with a stranger. In a review of these studies, Coan had this to say:

Subjects inside a brain scanner (fMRI) held hands with either a marital partner, a friend, or a stranger positioned outside the scanner. When exposed to (mild) electrical shocks (psychologists’ favourite way to induce stress) these brain structures showed less activation (they were less “aroused”) when the subject was able to hold hands, even with a stranger. In a review of these studies, Coan had this to say:

“According to SBT, the human brain assumes proximity to social resources—resources that comprise the intrinsically social environment to which it is adapted… At its simplest, SBT suggests that proximity to social resources decreases the cost of climbing both the literal and figurative hills we face, because the brain construes social resources as bioenergetic resources, much like oxygen or glucose.”

The SBT experiments add an critical layer to what we know of isolation and stress: human proximity is processed by the brain as a physical, visceral presence. Other people are recognized by the brain not just via images on a screen or words packed in sound waves, but through actual physical closeness, optimized by the sense of touch. Even being in the same room as others, being close by, provides a fundamental context — a baseline — for handling adversity and stress. Think of being in a movie theatre, a waiting room, or in your own den watching TV with someone else. No speech is required to feel the irrepressible sense of closeness that comes with proximity itself.

I hear my friends and family talking about “Zoom fatigue.” For a reason. Zooming is way way better than no communication at all. But it’s still a partial measure. Texting, Tweeting, Instagram, and other platforms that rely (at least partially) on written characters provide even less of the colour, or tone, or the physicality of mammalian communication. Our brains are full of semantics, words and ideas, and we love exchanging these, exploring and building on them. That’s great. But our brains are part of our bodies, so the sense of comfort and care we get from others comes from an evolutionary heritage tens of millions of years old. A heritage that’s primarily nonverbal.

I hear my friends and family talking about “Zoom fatigue.” For a reason. Zooming is way way better than no communication at all. But it’s still a partial measure. Texting, Tweeting, Instagram, and other platforms that rely (at least partially) on written characters provide even less of the colour, or tone, or the physicality of mammalian communication. Our brains are full of semantics, words and ideas, and we love exchanging these, exploring and building on them. That’s great. But our brains are part of our bodies, so the sense of comfort and care we get from others comes from an evolutionary heritage tens of millions of years old. A heritage that’s primarily nonverbal.

Even with all the digital media at our disposal, it’s been a lonely year. And that 30% increase in overdose deaths counts as a reflection of how hard it’s been for many of us. We seem to be starting to conquer Covid-19, at least in the Western world. Let’s keep it up, and let’s spread the wealth. That includes getting vaccinated, so we can protect our families and communities while protecting ourselves. It’s gotta be a group effort, and the group includes humans everywhere. People like us, all over the world, who need to come out of hiding.

Even with all the digital media at our disposal, it’s been a lonely year. And that 30% increase in overdose deaths counts as a reflection of how hard it’s been for many of us. We seem to be starting to conquer Covid-19, at least in the Western world. Let’s keep it up, and let’s spread the wealth. That includes getting vaccinated, so we can protect our families and communities while protecting ourselves. It’s gotta be a group effort, and the group includes humans everywhere. People like us, all over the world, who need to come out of hiding.

Leave a Reply