The paper I recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (linked here, summary linked here) detailed my best arguments against the disease model of addiction. But it also explored new territory, and that’s the topic of today’s post.

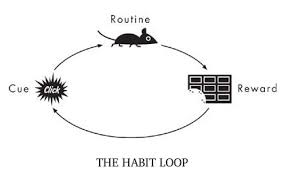

I emphasized (as I have for years) that addiction is learned. It is not a pathology but a learned package of desires, actions and expectancies that keep leading back to the same reward. We call it a reward, but most of us who’ve been through it know that the experience itself gets less rewarding  even as the desires and expectancies continue to strengthen. Is that pathological? No more than being in love with a hurtful partner, or praying to an unresponsive god, or being devoted to a sports team despite their string of losses. When the power of a reward arises from strong emotions and needs, the tendency to pursue it isn’t rational. When we seek and find that thing again and again, then, through learning,

even as the desires and expectancies continue to strengthen. Is that pathological? No more than being in love with a hurtful partner, or praying to an unresponsive god, or being devoted to a sports team despite their string of losses. When the power of a reward arises from strong emotions and needs, the tendency to pursue it isn’t rational. When we seek and find that thing again and again, then, through learning,  the synapses of our brain form into dense networks (pathways of connected neurons) that become very difficult to circumvent. Learning on overdrive, through repetitive need-satisfaction, is habit formation — addiction is a deep and insidious habit.

the synapses of our brain form into dense networks (pathways of connected neurons) that become very difficult to circumvent. Learning on overdrive, through repetitive need-satisfaction, is habit formation — addiction is a deep and insidious habit.

Well, you’ve heard me go on about this before, and my second addiction book, The Biology of Desire, makes the point pretty well. But my recent article came out in a journal read by more doctors than any other journal in the world. To convince that audience, I tried (with the help of Shaun Shelly, who co-wrote or edited much of it) to show that each of the brain changes highlighted by the disease model are not pathological. They’re the sorts of brain changes you’d expect when  expectancies and emotions become attached to a specific goal, leading to behaviours that are partly automatic — and partly not. Habit formation results in automaticity, sensitization to some rewards, and desensitization to others. The brain changes seen in addiction are just the biological underpinnings of this natural learning progression. And…they can continue to update; they’re not carved in stone.

expectancies and emotions become attached to a specific goal, leading to behaviours that are partly automatic — and partly not. Habit formation results in automaticity, sensitization to some rewards, and desensitization to others. The brain changes seen in addiction are just the biological underpinnings of this natural learning progression. And…they can continue to update; they’re not carved in stone.

The new territory I wanted to explore sits outside the brain, in the world, in the environment of the addict (I use that term without disdain or judgement, having been one myself). Our environment, especially our social environment, consists of the people we care about, many of whom care about us, and of opportunities for care, for sharing, for pleasure, for relief, for a sense of fulfillment. These opportunities require certain resources, such as social skills, knowledge, self-esteem (at least a little), financial stability, the capacity to understand others. Opportunities are bridges between our needs and their satisfaction. Resources are the capital we use to pursue them.

When people fall into addiction, their environments shrink around them. Good friends, stable romantic partners, available, loving family members, physical comforts such as a safe place to live, job opportunities, and all the rest of it, gradually become less available. The opportunities for getting them back also become less available. Our attention and motivation, riveted now to just one source of satisfaction, lose their connection with the other sources of satisfaction that “normal” people enjoy. I see this as a literal narrowing or shrinking of the environment. Because of what I’ve called “now appeal” — or simply habit strength or deeply learned habitual behaviour patterns — we focus only on what’s in front of us and forget how to go after other rewards. So other rewards fade in availability. They evaporate. They get lost.

When I was an addict, I lost close friends, I lost a woman I loved, I lost the opportunity to communicate honestly with my parents, I lost money, I lost a sense of social and physical safety, I got kicked out of school and lost that opportunity (for a while) and all the rest of it. This picture is typical, one way or another.

But what blows me away conceptually is how this narrowing of the available, reachable, usable social environment precisely parallels the narrowing going on in one’s brain. My synapses fell in line, in pathways and networks that had a single purpose, so to speak, rather than multiple pathways supporting

But what blows me away conceptually is how this narrowing of the available, reachable, usable social environment precisely parallels the narrowing going on in one’s brain. My synapses fell in line, in pathways and networks that had a single purpose, so to speak, rather than multiple pathways supporting  multiple purposes. This “narrowing” in the brain corresponded with a shrinking or narrowing in my available environment. Neither is pathological. Both, especially both together, create a kind of prison.

multiple purposes. This “narrowing” in the brain corresponded with a shrinking or narrowing in my available environment. Neither is pathological. Both, especially both together, create a kind of prison.

Perhaps of interest to those into philosophy or psychology, this tendency has been studied as a universal feature of living organisms. The sensory and behavioural specialties of a species get synchronized with aspects of that species’ environment. Both change together. This can happen over evolutionary time. But it can also happen at the scale of human development, as I’m talking about here. The study of this process is called “embodied cognition.” Google it.

One more point made in the article that Shaun and I thought was crucially important: people who study addiction know that there are massive correlations between early adversity (e.g., neglect, abuse, poverty, racial segregation, parental depression, parental alcoholism — in childhood or adolescence) and the probability of becoming addicted later in life. When thinking about how the narrowing environment corresponds with the narrowing of brain function, we can see that the addict’s environment starts off narrow! Kids with happy, healthy social-emotional worlds, who have not experienced trauma, rarely become addicts.

One more point made in the article that Shaun and I thought was crucially important: people who study addiction know that there are massive correlations between early adversity (e.g., neglect, abuse, poverty, racial segregation, parental depression, parental alcoholism — in childhood or adolescence) and the probability of becoming addicted later in life. When thinking about how the narrowing environment corresponds with the narrowing of brain function, we can see that the addict’s environment starts off narrow! Kids with happy, healthy social-emotional worlds, who have not experienced trauma, rarely become addicts.

It’s really so simple. The narrowing begins early, sometimes even before birth — look to the family of origin. (Gabor Maté has emphasized the impact of adversity in early childhood. Bruce Alexander targets sociocultural adversity.) This helps us understand how environments and brains influence each other all the way along. If your childhood is hampered by obstacles and dead-ends, whether emotional, social, financial, or some combination of these, the narrowing has already begun.

the proliferation of gun ownership in the US and the political voices that advocate it. I guess you could say it’s an emotional topic for both of us. But we differed on a sort of thought experiment: What would it be like if people could make guns on a 3D printer and those guns were entirely untraceable? Would that be a bad thing because there’d be more guns around (her point) or a good thing because the NRA and its right-wing supporters would lose their influence (my point)? The content of the argument hardly matters. Neither of us had ever thought about plastic guns before. We were speculating, and then discussing, and then debating.

the proliferation of gun ownership in the US and the political voices that advocate it. I guess you could say it’s an emotional topic for both of us. But we differed on a sort of thought experiment: What would it be like if people could make guns on a 3D printer and those guns were entirely untraceable? Would that be a bad thing because there’d be more guns around (her point) or a good thing because the NRA and its right-wing supporters would lose their influence (my point)? The content of the argument hardly matters. Neither of us had ever thought about plastic guns before. We were speculating, and then discussing, and then debating. making really good points, I told myself. I’m winning the debate. Through parry and thrust (in the language of fencing) I tried to take her down. To defeat her. All I really cared about was being right.

making really good points, I told myself. I’m winning the debate. Through parry and thrust (in the language of fencing) I tried to take her down. To defeat her. All I really cared about was being right. What I didn’t see until the next day was that Jane was hurt. She perceived my arguments as weapons — and indeed they were. I had thought: given competing positions, someone’s going to win, and that’s going to be me. She had thought: why is he putting me down? Why is he trying to cast my opinions as groundless and stupid?

What I didn’t see until the next day was that Jane was hurt. She perceived my arguments as weapons — and indeed they were. I had thought: given competing positions, someone’s going to win, and that’s going to be me. She had thought: why is he putting me down? Why is he trying to cast my opinions as groundless and stupid? going about it? Do I really want to change the minds of people steeped in medical thinking, addicts who believe they’re ill, their families, their doctors? Or do I just want to win a debate?

going about it? Do I really want to change the minds of people steeped in medical thinking, addicts who believe they’re ill, their families, their doctors? Or do I just want to win a debate? So I’m watching Matt facilitate a SMART meeting in Boston last night. SMART sometimes construes itself as “the alternative to AA.” SMART offers psychological tools, such as focusing on one’s own thought patterns and beliefs, and the potential that offers for behaviour change, even by small increments. SMART lends itself to mindfulness practices, it neither shames nor exonerates those who’ve “relapsed.” It is inclusive, it does its best to avoid dogma. And it values honesty and fellowship — as does its sometimes querulous cousin, AA.

So I’m watching Matt facilitate a SMART meeting in Boston last night. SMART sometimes construes itself as “the alternative to AA.” SMART offers psychological tools, such as focusing on one’s own thought patterns and beliefs, and the potential that offers for behaviour change, even by small increments. SMART lends itself to mindfulness practices, it neither shames nor exonerates those who’ve “relapsed.” It is inclusive, it does its best to avoid dogma. And it values honesty and fellowship — as does its sometimes querulous cousin, AA. thinking habits, to see their substance use more rationally, more comprehensively. But more than that, he was listening carefully to what people said and grasping what they were feeling: their fears, vulnerabilities, and their (often tattered) self-esteem.

thinking habits, to see their substance use more rationally, more comprehensively. But more than that, he was listening carefully to what people said and grasping what they were feeling: their fears, vulnerabilities, and their (often tattered) self-esteem.

able to access these medications on demand—in hospitals, doctor’s offices, emergency rooms and syringe exchange programs…. No urines or counseling or abstinence from opioids or other substances should be required to get these drugs, just as those barriers are not imposed on people with other disorders who need medication.

able to access these medications on demand—in hospitals, doctor’s offices, emergency rooms and syringe exchange programs…. No urines or counseling or abstinence from opioids or other substances should be required to get these drugs, just as those barriers are not imposed on people with other disorders who need medication. Simultaneously…many doctors have

Simultaneously…many doctors have  The result is tens of thousands of patients—many of whom were formerly medically stable—being left in pain, increased disability and withdrawal.

The result is tens of thousands of patients—many of whom were formerly medically stable—being left in pain, increased disability and withdrawal.  into care for those who decide they do want additional help…If you are successfully managing any ongoing mental health issues, you don’t need to keep showing up at a clinic.

into care for those who decide they do want additional help…If you are successfully managing any ongoing mental health issues, you don’t need to keep showing up at a clinic. In order to save lives, we need safer consumption spaces (or better yet, call them “overdose prevention sites”) in areas where drug use and sales are concentrated…

In order to save lives, we need safer consumption spaces (or better yet, call them “overdose prevention sites”) in areas where drug use and sales are concentrated… We also need shelters and housing, separate from those aimed at stabilization and abstinence, for people who are actively addicted, many of whom are also mentally ill and have symptoms related to severe trauma. When people have safe places to live and to use drugs, they are both much more likely to survive and much more likely to find ways to sustained recovery.

We also need shelters and housing, separate from those aimed at stabilization and abstinence, for people who are actively addicted, many of whom are also mentally ill and have symptoms related to severe trauma. When people have safe places to live and to use drugs, they are both much more likely to survive and much more likely to find ways to sustained recovery. also tend to be based on a 12-step ideology, which is fine for those who find that pathway amenable, but not for those who don’t—and not when that ideology is interpreted to stigmatize and discourage medication use.

also tend to be based on a 12-step ideology, which is fine for those who find that pathway amenable, but not for those who don’t—and not when that ideology is interpreted to stigmatize and discourage medication use. current administration—it may soon be possible.

current administration—it may soon be possible.

the cut-off between a pass and a fail? (That was the cut point when I was an undergrad.) So you’ve spent much of the week partying, getting high, etc, and here comes the exam, and you cram for it that morning, give it your best shot, and wait anxiously for the result. A

the cut-off between a pass and a fail? (That was the cut point when I was an undergrad.) So you’ve spent much of the week partying, getting high, etc, and here comes the exam, and you cram for it that morning, give it your best shot, and wait anxiously for the result. A  week later the prof hands out the exams, or you look up your grade on the bulletin board, and the thing you care about more than anything else is whether you got at least a 65. If you got a 64, you’re shit out of luck. If you got a 66, you’re sailing.

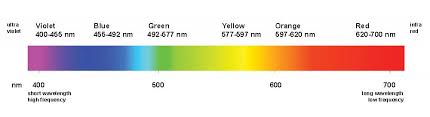

week later the prof hands out the exams, or you look up your grade on the bulletin board, and the thing you care about more than anything else is whether you got at least a 65. If you got a 64, you’re shit out of luck. If you got a 66, you’re sailing. is a spectrum, a dimension, a set of gradations at best — nothing like an all-or-nothing category. Yet the disease label cannot help but classify addiction as a category. You either have tuberculosis, or diabetes, or cancer, or you don’t. Never mind that, when it comes to addiction, the category label itself can do more harm than good. As soon as you classify addiction as a disease, you draw a line. (There is some discussion of this issue in

is a spectrum, a dimension, a set of gradations at best — nothing like an all-or-nothing category. Yet the disease label cannot help but classify addiction as a category. You either have tuberculosis, or diabetes, or cancer, or you don’t. Never mind that, when it comes to addiction, the category label itself can do more harm than good. As soon as you classify addiction as a disease, you draw a line. (There is some discussion of this issue in

I’ve been working with a client (I’ll call him Robert) who’s trying to stop using cocaine. We’ve had some powerful sessions lately, emotionally moving for me as well as for him. I really want to help Robert — or, more to the point, I want him to succeed, with or without my help. He’s just so miserable, so alone, so desperate.

I’ve been working with a client (I’ll call him Robert) who’s trying to stop using cocaine. We’ve had some powerful sessions lately, emotionally moving for me as well as for him. I really want to help Robert — or, more to the point, I want him to succeed, with or without my help. He’s just so miserable, so alone, so desperate. despised by others…and by oneself. Shame is hot, red like a boil, painful, laced with disgust. The shamed self often gives way to anger, the famous fuck-you reaction, or defiance, the equally famous fuck-it solution. Or it opens onto

despised by others…and by oneself. Shame is hot, red like a boil, painful, laced with disgust. The shamed self often gives way to anger, the famous fuck-you reaction, or defiance, the equally famous fuck-it solution. Or it opens onto  guilt and depression. Omigod, how could I have done that?! What a bastard I am. Then there’s the anxiety about being caught, seen, punished, cast out — as familiar as background music to Robert and to just about everyone I know in active addiction. Often there’s a cascade through several of these self-states that leads straight to using. But each state is also a branch of our personality, stable and familiar — a thicket of interlaced neurons.

guilt and depression. Omigod, how could I have done that?! What a bastard I am. Then there’s the anxiety about being caught, seen, punished, cast out — as familiar as background music to Robert and to just about everyone I know in active addiction. Often there’s a cascade through several of these self-states that leads straight to using. But each state is also a branch of our personality, stable and familiar — a thicket of interlaced neurons. Yet there’s another self, built on another feeling. It’s the compassionate self, based on the feeling of nurturance. Nurturance is built into our neural hardware. It’s needed for us (great apes) to effectively raise our young, since they take forever to mature. It’s

Yet there’s another self, built on another feeling. It’s the compassionate self, based on the feeling of nurturance. Nurturance is built into our neural hardware. It’s needed for us (great apes) to effectively raise our young, since they take forever to mature. It’s  the feeling we feel when we comfort a child or feed a helpless animal. But, as you probably know, the compassionate self seems a fiction, a fantasy, when you’re in active addiction, especially when it comes to compassion for yourself. Maybe you never learned self-compassion deeply enough because your parents didn’t know how

the feeling we feel when we comfort a child or feed a helpless animal. But, as you probably know, the compassionate self seems a fiction, a fantasy, when you’re in active addiction, especially when it comes to compassion for yourself. Maybe you never learned self-compassion deeply enough because your parents didn’t know how  to provide it or feel it or value it. Or maybe you lost it en route. It gets worn thin by repeated bouts of shame and self-loathing.

to provide it or feel it or value it. Or maybe you lost it en route. It gets worn thin by repeated bouts of shame and self-loathing. In The Biology of Desire I described self-compassion as one way to connect your past self (recognizing how much you’ve been hurt) with your present self (of course I want to get high — that’s how I’ve learned to hurt less) with your future self (we’re going to get to a better place — here we go). Note the use of “we” — and (P.S.) see Peter Sheath’s and Matt’s comments directly below.

In The Biology of Desire I described self-compassion as one way to connect your past self (recognizing how much you’ve been hurt) with your present self (of course I want to get high — that’s how I’ve learned to hurt less) with your future self (we’re going to get to a better place — here we go). Note the use of “we” — and (P.S.) see Peter Sheath’s and Matt’s comments directly below. Given that self-compassion looks like a field of dead weeds, the macro project is simple. Cultivate it. Grow it. Make it more familiar, more salient, more present. There are several ways to do this.

Given that self-compassion looks like a field of dead weeds, the macro project is simple. Cultivate it. Grow it. Make it more familiar, more salient, more present. There are several ways to do this.  person sensing light. Feel that first bit of coziness behind your eyelids, in your body, and stay with it, let it warm you. I suggested he try using a meditation app, like

person sensing light. Feel that first bit of coziness behind your eyelids, in your body, and stay with it, let it warm you. I suggested he try using a meditation app, like