A community-based treatment initiative that just might work

Some of the comments following my last post asked the same question — and it needed to be asked: How might you apply this perspective? What kind of treatment program would embody these concepts? Let’s get concrete…how would it work?

I more or less ended that post with the following proclamation (copied here, in part, from that post):

Any approach that meets addicts when and where they’re ready to quit is well positioned to help them move onward. Community-based settings can fill this role most easily, because…there is no line-up at the door… Nor, hopefully, are there rigid policies that preempt the addict’s personal incentive. When desire is ready to arc from the goal of immediate relief to the goal of a valued future, treatment can begin. Not by inducing desire—only frustration and suffering can do that—but by capturing and holding one’s vision of that future…[while the desire knob is turned up to max.]

Or, to put it in terms of the biology, “what will work best is whatever is available when the synaptic avenues of desire make contact with brain regions responsible for perspective change.”

But you often need other people — either one person or a group of people — to hold those elements in place, to help make it happen. Which is why treatment must be interpersonal if it’s to have any chance of working.

So, at the end of the book, and here in today’s post, I provide an example that captures the critical importance of striking while the iron is hot — when desire is turned up high and synched (for the moment) with the vision of a future self free of addiction. It’s a radical treatment initiative that  uses “other people” at the grass roots level, to hold the pieces together before the iron cools. And it’s been inspired and shaped by my friend Peter Sheath, a former addict and senior associate of a consulting group for service delivery in the U.K. Thank you, Peter, for inspiring me with your description of this exciting venture.

uses “other people” at the grass roots level, to hold the pieces together before the iron cools. And it’s been inspired and shaped by my friend Peter Sheath, a former addict and senior associate of a consulting group for service delivery in the U.K. Thank you, Peter, for inspiring me with your description of this exciting venture.

The city of Birmingham (the second largest in England) is investing massively in this pilot program, designed to provide help for addicts at the very moment when their desire for change is ignited. Treatment nodes are distributed across the community, through sites that are most available to addicts in their day-to-day lives. Shopkeepers, including newsagents,

The city of Birmingham (the second largest in England) is investing massively in this pilot program, designed to provide help for addicts at the very moment when their desire for change is ignited. Treatment nodes are distributed across the community, through sites that are most available to addicts in their day-to-day lives. Shopkeepers, including newsagents,  bakers, butchers, and pharmacists, are trained in brief interventions. Participants’ shops display an ROR (“Reach Out Recovery”) sticker on the front window, so that addicts immediately see that they are “recovery-friendly” and ready to help. People come in off the street, perhaps buying a loaf of bread at the same time, and say “I’ve had enough! I’m ready to

bakers, butchers, and pharmacists, are trained in brief interventions. Participants’ shops display an ROR (“Reach Out Recovery”) sticker on the front window, so that addicts immediately see that they are “recovery-friendly” and ready to help. People come in off the street, perhaps buying a loaf of bread at the same time, and say “I’ve had enough! I’m ready to  quit!” Then the shopkeeper tells them they’ve come to the right place, takes a quick inventory, and advises them on what to do next. “Hey, reduce your drinking a bit, and then pop by and talk with me this afternoon or tomorrow.” Or, in more severe cases, “I won’t be able to work with you but I know somebody who can.” People can be referred

quit!” Then the shopkeeper tells them they’ve come to the right place, takes a quick inventory, and advises them on what to do next. “Hey, reduce your drinking a bit, and then pop by and talk with me this afternoon or tomorrow.” Or, in more severe cases, “I won’t be able to work with you but I know somebody who can.” People can be referred  to “peer mentors” who will show up the following day to help them with difficult issues such as detox and other medical matters. Even taxi drivers have been recruited, so that someone en route to score can throw up his hands and call it quits without that incentive getting lost in translation.

to “peer mentors” who will show up the following day to help them with difficult issues such as detox and other medical matters. Even taxi drivers have been recruited, so that someone en route to score can throw up his hands and call it quits without that incentive getting lost in translation.

Obviously the community needs to be motivated to make this happen. But that’s a boon in itself, because it recasts the problem of addiction as everyone’s problem, not the burden of the individual alone. (Shades of Rat Park!) So the support is there, the immediacy is there, and the infrastructure is built and organized without any religious or medical axe to grind. And it’s free. The funding comes from the city, not from the addict’s already-stretched family.

I see this as a highly creative approach. Whether it will work as well as we hope remains to be seen. The project is inspired by intuitions about the mercurial nature of desire and the power it bestows on our most essential plans — an intuition that fits what we know of the neurophysiology of addiction. More generally, the project exemplifies the innovation and insight that can sprout when the disease model is retracted and a fresh perspective, free of orthodoxy and special interests, is allowed take in its place.

Though outwardly I was the soul of enthusiastic compliance with my treatment, the questions were brewing. I didn’t think that character defects and self-centeredness had caused my alcohol problems. I had no interest in spending my life confessing my sins to strangers. And I wasn’t convinced that a lifelong abstinence from any mood-altering chemical (except caffeine, sugar and nicotine!) was the only answer.

Though outwardly I was the soul of enthusiastic compliance with my treatment, the questions were brewing. I didn’t think that character defects and self-centeredness had caused my alcohol problems. I had no interest in spending my life confessing my sins to strangers. And I wasn’t convinced that a lifelong abstinence from any mood-altering chemical (except caffeine, sugar and nicotine!) was the only answer. We don’t require anything, other than that members treat each other with respect and not judgement. We support abstinence (a word we prefer over “sobriety,” as “sober” has moral connotations), moderate drinking, and safe drinking.

We don’t require anything, other than that members treat each other with respect and not judgement. We support abstinence (a word we prefer over “sobriety,” as “sober” has moral connotations), moderate drinking, and safe drinking. For me, HAMS has been a critical part of rewriting my identity. The label “alcoholic” seemed to erase everything I had been before, and everything I might be in the future. No matter what I did, even when I didn’t drink, I felt shame. HAMS has taught me that the content of my bloodstream is not the content of my character. Now my identity is not defined by my relationship to alcohol. I am not an “alcoholic.” I am April Wilson Smith.

For me, HAMS has been a critical part of rewriting my identity. The label “alcoholic” seemed to erase everything I had been before, and everything I might be in the future. No matter what I did, even when I didn’t drink, I felt shame. HAMS has taught me that the content of my bloodstream is not the content of my character. Now my identity is not defined by my relationship to alcohol. I am not an “alcoholic.” I am April Wilson Smith. HAMS has just published

HAMS has just published  Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube.

Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube.  But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it.

with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it. I’ll end with a

I’ll end with a  themselves, sometimes despite vast challenges (including abuse of one kind or another) during childhood and/or adolescence. And I’ve helped people devise cognitive tricks to shunt their trajectory away from substance use and toward more satisfying habits.

themselves, sometimes despite vast challenges (including abuse of one kind or another) during childhood and/or adolescence. And I’ve helped people devise cognitive tricks to shunt their trajectory away from substance use and toward more satisfying habits. But there seems to be a black hole in the centre of the addiction galaxy that sucks in techniques of every sort and laughingly squishes them to nothing, tosses them back down some wormhole to some parallel universe. And surely that’s because addiction boils down to a unique “thing” which is totally psychological, totally biological, and totally social. A habit in the workings of our cells, our minds, and our interpersonal relations.

But there seems to be a black hole in the centre of the addiction galaxy that sucks in techniques of every sort and laughingly squishes them to nothing, tosses them back down some wormhole to some parallel universe. And surely that’s because addiction boils down to a unique “thing” which is totally psychological, totally biological, and totally social. A habit in the workings of our cells, our minds, and our interpersonal relations. later) you’re often left with an aching emptiness. And what the hell are we humans supposed to do with that?! (Mindfulness/meditation has some answers, but let’s face it, the solution isn’t obvious.)

later) you’re often left with an aching emptiness. And what the hell are we humans supposed to do with that?! (Mindfulness/meditation has some answers, but let’s face it, the solution isn’t obvious.)

IFS

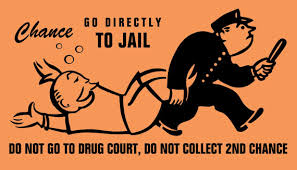

IFS addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black.

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black. The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride.

The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride. Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments