Hi again. It’s me this time. No guests. I want to tell you about the debate I just had with a high priest of the Disease Church. Not the bishop, Nora Volkow. But her second in command, George Koob.

Those of us who oppose the disease label have been trying to organize a real debate for a long time. Nora Volkow has consistently ignored these requests or else replied No through her staff. But Koob made an

excellent second choice. Judging by his picture and digital presence, I expected a slightly stodgy, soft-spoken academic/scientist type who saw addiction as a disease.

excellent second choice. Judging by his picture and digital presence, I expected a slightly stodgy, soft-spoken academic/scientist type who saw addiction as a disease.

In fact Dr. Koob is the second author of the paper first-authored by Volkow in the January issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, the paper that made a lot of us anti-disease people more irate than usual. Here’s the title: Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. And here’s a passage from the first paragraph:

In the past two decades, research has increasingly supported the view that addiction is a disease of the brain. Although the brain disease model of addiction has yielded effective preventive measures, treatment interventions, and public health policies to address substance-use disorders, the underlying concept of substance abuse as a brain disease continues to be questioned…

I used this quote to launch a counterattack that was published last week in the Guardian. I was pleased to see my little fusillade appear on page 1 of the US edition last Tuesday. And it’s snagged over 600 comments and 2,700 shares in the first week. So a lot of people seemed to agree with my criticisms of the disease model (specifically the claim that the disease label led to an “effective” response to addiction and reduced stigma). But, if you happen to browse the comments, you’ll see that many others thought I was out to lunch.

I actually wondered whether Koob had already read my article. Because he seemed hopping mad from the first words of the debate.

Here’s how it went.

I was sitting in a flashy looking studio in Arnhem. Yes, even in my town we have studios with lots of computers and screens and expensive looking microphones. So I was sitting there in a sound-proof room in front of a state-of-the-art mic, and George Koob was in Washington. The debate was set up by CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corp — Canada’s national radio) and will be broadcast a few weeks from now. I’ll let you know.

I was nervous. More nervous than I’ve been in any kind of talk or interview for a long time. My voice came out raspy at first. Yet I’d done my homework. I’d reread lots of stuff on changes to the dopamine system, Berridge’s review of his incentive sensitization model, findings on the desensitization of the striatum and the resultant loss of connectivity with the prefrontal cortex. I’d also scanned articles showing that these brain changes are common to drug addiction, porn addiction, obesity, “internet addiction,” and even compulsive shopping — so I had a few arguments ready.

I’d also read a few Koob papers (which I forgot I’d already read thoroughly until I found my yellow highlighting throughout) and felt completely caught up on his theory of the “dark side” of addiction, viz withdrawal, viz the rebound invoked by the “antireward” system. I was ready to talk brain science, because I had no doubt (and I still have no doubt) that George Koob is a top neuroscientist, highly respected and rightfully so. Not to mention the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

But within minutes of the word Go, I realized that I’d done all that cramming for nothing. This debate wasn’t going to be about the neuroscience of addiction. It wasn’t going to be smart, sophisticated, strategic, or fun. It was going to be a slug fest.

The moderator/host (a seasoned radio/TV person in Toronto) started things off by asking Koob: Why do you say addiction is a disease?

He replied something like: What else could it be? And when she asked for a bit more substance: Because it changes the brain. It’s as simple as that. That’s what he said, almost verbatim. And I thought: that’s the most vacuous argument he could possibly make. Everybody knows that the brain is always changing, it changes whenever we learn something, it changes massively throughout development, and there’s this thing called neuroplasticity which is basically the brain’s job description. But that’s what he said: addiction is a disease because it changes the brain. So I had to retort with…well, some version of what I just said.

It didn’t get any better. He sounded angry throughout. He was belligerent at times. He talked about how four people he was very close to had died from alcoholism, because they could not stop drinking. Absolutely could not stop. And he specifically accused me (and us anti-disease folk) of trivializing addiction by not recognizing that it’s a disease. I told him I’d lost a friend to addiction too, but I wasn’t pleased with myself for stooping to such arguments. He even said that I wanted addicts to be stigmatized and that’s why I opposed the disease label. Which was exactly the opposite of what I’d just said: that I felt the disease label merely entrenched the stigma of addiction, and there were much better ways to overcome stigma, like connection, compassion…all the things Johann Hari writes about….and understanding what it really is without giving it a simplistic label.

I’d better stop. I don’t remember everything, and maybe my memories are blurred by the adrenalin I was surfing through most of the debate….which lasted about 45 minutes.

But here’s the point I want to make. I’m pretty sure I “won” the debate because I said smarter things and backed them up better than my opponent. And I’m pretty sure I came off smelling sweeter because my tone wasn’t as antagonistic as his.

BUT IT DOESN’T MATTER.

The problem is that we weren’t talking. We were just fighting. We weren’t listening to each other. We weren’t getting to know each other’s views any better. We certainly weren’t arriving at some kind of middle ground that might benefit from both our perspectives.

And that is so sad!

to one extent or another. They both kill many times more people each year than all illegal substances combined, even in the midst of the opiate “epidemic”. Yet, we manage to find

to one extent or another. They both kill many times more people each year than all illegal substances combined, even in the midst of the opiate “epidemic”. Yet, we manage to find  (admittedly imperfect) ways to deal with the harms they cause as best we can. We do this because we recognize that the harms of prohibiting these substances would likely be significantly greater than simply finding more effective ways to live with them.

(admittedly imperfect) ways to deal with the harms they cause as best we can. We do this because we recognize that the harms of prohibiting these substances would likely be significantly greater than simply finding more effective ways to live with them. steadily each year — making it the #2 cause of preventable death (behind good ole’ tobacco). And the data strongly suggest that households with just one obese parent are at least twice as likely to raise obese children who are doomed to a shorter life expectancy than their parents. Using drug war logic, this ought to be as good a reason as any to criminalize obesity or the behaviors (and foods) that “cause” it.

steadily each year — making it the #2 cause of preventable death (behind good ole’ tobacco). And the data strongly suggest that households with just one obese parent are at least twice as likely to raise obese children who are doomed to a shorter life expectancy than their parents. Using drug war logic, this ought to be as good a reason as any to criminalize obesity or the behaviors (and foods) that “cause” it. Sound crazy? That’s how crazy drug criminalization and drug courts seem to me now. Having dealt with my daughter’s heroin addiction for the past five years, it really hit me, after her most recent “relapse” (for lack of a better term) a little over a year ago, that it wasn’t so much her

Sound crazy? That’s how crazy drug criminalization and drug courts seem to me now. Having dealt with my daughter’s heroin addiction for the past five years, it really hit me, after her most recent “relapse” (for lack of a better term) a little over a year ago, that it wasn’t so much her  addiction that was causing the pain and trauma we were both experiencing as it was dealing with the woefully ineffective — and often counterproductive and EXPENSIVE — U.S. legal and treatment systems.

addiction that was causing the pain and trauma we were both experiencing as it was dealing with the woefully ineffective — and often counterproductive and EXPENSIVE — U.S. legal and treatment systems. Because while we labor under the delusion that prohibiting a given substance outright is the ultimate form of control, it is in fact the mechanism by which we relinquish all control to criminals, who have in turn been empowered by such policies to build massive global organizations. The only way to undercut that power is to minimize the enormous profits that are generated by prohibitionist policies.

Because while we labor under the delusion that prohibiting a given substance outright is the ultimate form of control, it is in fact the mechanism by which we relinquish all control to criminals, who have in turn been empowered by such policies to build massive global organizations. The only way to undercut that power is to minimize the enormous profits that are generated by prohibitionist policies. the case of opioids, prevention of leakage or diversion to others, policies for supervision and safety, and strict constraints on who might be eligible for prescriptions. One model of a successful quasi-legalization policy comes from Switzerland, which implemented heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) with great success to stem the tide of its own heroin epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Here is a brief description of the outcome from

the case of opioids, prevention of leakage or diversion to others, policies for supervision and safety, and strict constraints on who might be eligible for prescriptions. One model of a successful quasi-legalization policy comes from Switzerland, which implemented heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) with great success to stem the tide of its own heroin epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Here is a brief description of the outcome from  given your heroin there, for free, where you use it supervised by a doctor or nurse. You are given support to turn your life around, and find a job, and housing.

given your heroin there, for free, where you use it supervised by a doctor or nurse. You are given support to turn your life around, and find a job, and housing.

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black.

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black. The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride.

The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride. Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

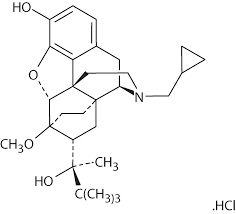

many of the issues that have made drug use so meaningful to them. It also reduces the spread of HIV. Through robust head-to-head clinical trials, buprenorphine has also been shown to be effective, in some cases more so, in some cases less, but it is effective and has a better safety profile.

many of the issues that have made drug use so meaningful to them. It also reduces the spread of HIV. Through robust head-to-head clinical trials, buprenorphine has also been shown to be effective, in some cases more so, in some cases less, but it is effective and has a better safety profile. As far as diversion is concerned, diversion is a function not of greater availability but of lack of availability. The diversion of methadone and buprenorphine occurs because they have a street value — because people cannot access these medications or because the services that offer them are not attractive to them. This is basic economics, and it has been proven throughout history. Increased access through appropriate services will reduce diversion!

As far as diversion is concerned, diversion is a function not of greater availability but of lack of availability. The diversion of methadone and buprenorphine occurs because they have a street value — because people cannot access these medications or because the services that offer them are not attractive to them. This is basic economics, and it has been proven throughout history. Increased access through appropriate services will reduce diversion!