Behavioral addictions: You don’t need drugs or booze to be an addict

Hi from Hungary. I’m at a conference on behavioral addictions. Two days of talks by experts — psychologists, neuroscientists, psychiatrists, clinical researchers, etc. — who want to understand behavioral addictions. These include compulsive gambling, eating disorders, hypersexuality or sex addiction, and internet or gaming addiction. And I am really high on the flood of information, insight, commitment and good intentions, knowledge, creativity, blah blah blah, not to mention that I happen to be in Budapest, which looks like a magical kingdom from some angles and a Communist-bloc relic from others.

I knew so little about Hungary, I actually forgot the name of my destination when checking in for my flight in Amsterdam. I was standing at one of those automatic check-in terminals, had entered my passport information, and then when the prompt asked me for the first three letters of my destination, I blanked out. I asked the guy next to me, which was kind of embarrassing as he was deep in a conversation with someone else: What’s the capital of Hungary? He thought about it for awhile and then said “Bucarest”. I typed in BUC, and then realized that’s where my wife, Isabel, was born — and she’s Romanian, not Hungarian. It finally came:

Budapest

Coming in from the airport by cab, we crossed into another dimension. Mile after mile of hulking, dilapidated rectangular buildings, looking like they were last used 70 years ago to make bomb parts for the war. There was this stale ghost of leftover Communism everywhere. Everything looked shut down, grey slabs of concrete under a grey sky. This was Budapest?

My first surprise came when the driver demanded 5,450 for the ride. What? This could be trouble. But it turned out that 5,450 whatevers translated to 20 euros. Whew. My next surprise was how beautiful the inner city turned out to be. At some invisible line the Communist-era shabbiness rolled back to reveal a land of Oz: Enormous but gorgeous monuments to a thousand years of changing architecture — churches, castles, museums, fountains — with elaborate arches and elegant turrets, tapering to slender needles pointed at the sky. All connected by wide avenues, full of shoppers, and bridges that appeared to be held up by steel lace. History oozing out of every stone in every facade.

The third surprise was that the talks were so riveting I was hardly tempted by the marvels just outside the door. In two days I learned so much, met so many amazing people, discovered new research strategies, new devices, new recovery tools. For example, today I chatted for an hour with a man named Robert Pretlow, who spent two years — full-time — developing

The third surprise was that the talks were so riveting I was hardly tempted by the marvels just outside the door. In two days I learned so much, met so many amazing people, discovered new research strategies, new devices, new recovery tools. For example, today I chatted for an hour with a man named Robert Pretlow, who spent two years — full-time — developing a cell-phone app, and a couple of decades studying child and adult eating disorders. This app (displayed on the right — so far only available for research) lets you chat with other recovering individuals, warns you about addictive triggers, reminds you about your own effective coping strategies, records your progress day by day. It’s like having a treatment centre in your pocket. Dr. Pretlow is using it to study eating disorders, but it seems that it could be applied to many other addictive problems as well. Bob agrees, but there is a lot of work to be done.

a cell-phone app, and a couple of decades studying child and adult eating disorders. This app (displayed on the right — so far only available for research) lets you chat with other recovering individuals, warns you about addictive triggers, reminds you about your own effective coping strategies, records your progress day by day. It’s like having a treatment centre in your pocket. Dr. Pretlow is using it to study eating disorders, but it seems that it could be applied to many other addictive problems as well. Bob agrees, but there is a lot of work to be done.

I learned about the hidden dangers in sex and gambling. This was not one of those conferences where you have to douse yourself with coffee to keep awake. I learned about the diversity of eating disorders — from binging, which looks a lot like  substance addiction, according to Marc N. Potenza at Yale — to anorexia — which looks more like over-control. A lot of talks focused on OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and quite a few speakers connected the compulsive nature of OCD with that of addiction. People talked about stages in the development of addiction (not far from the stages I listed the last couple of posts), and compared them with stages in the development of OCD. One guy showed how the addictive progression of stages coverged with the OCD progression — starting out in different places but ending up almost completely overlapping.

substance addiction, according to Marc N. Potenza at Yale — to anorexia — which looks more like over-control. A lot of talks focused on OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and quite a few speakers connected the compulsive nature of OCD with that of addiction. People talked about stages in the development of addiction (not far from the stages I listed the last couple of posts), and compared them with stages in the development of OCD. One guy showed how the addictive progression of stages coverged with the OCD progression — starting out in different places but ending up almost completely overlapping.

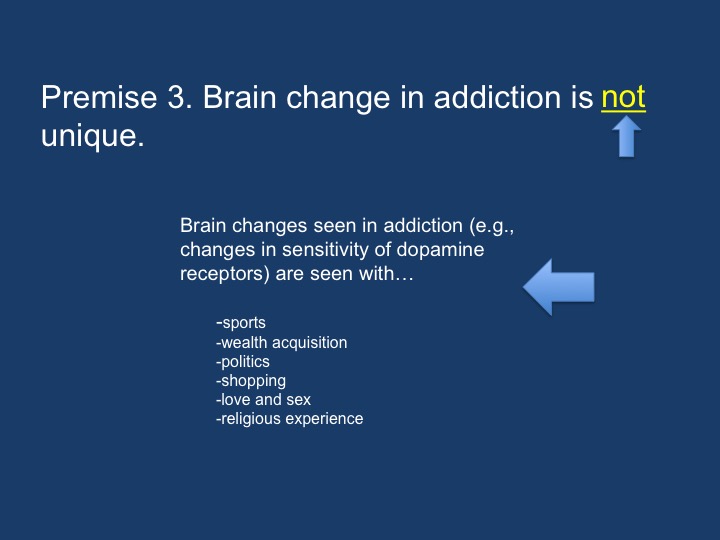

And these people weren’t just talking about behavior. There were neuroscience data in half the talks. The striatum was the overwhelming star of the show — the ventral striatum and its role in craving, and the dorsal  striatum responsible for compulsion. It appears that OCD sufferers talk about their compulsions a lot like addicts talk about their addictions. I don’t want to stop it. I know it’s bad for me, but it makes me feel better. And their brains light up in almost all the same places! In fact, their brains show changes in synaptic density (some areas getting more connected, other areas getting less connected) that look exactly like what you see in addicts, over the same time frame, as they get worse — or better.

striatum responsible for compulsion. It appears that OCD sufferers talk about their compulsions a lot like addicts talk about their addictions. I don’t want to stop it. I know it’s bad for me, but it makes me feel better. And their brains light up in almost all the same places! In fact, their brains show changes in synaptic density (some areas getting more connected, other areas getting less connected) that look exactly like what you see in addicts, over the same time frame, as they get worse — or better.

In just two days I learned so much, met with so many experts, exchanged email addresses, got books and papers handed to me…enough to keep me busy for quite a while.

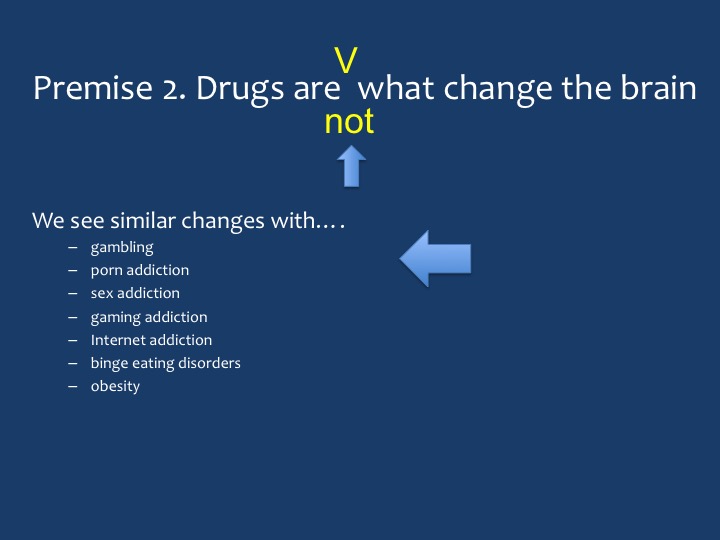

And to keep you busy! In the next few posts I’m going to try to synthesize what I’m learning about behavioral addictions — gambling, sex,  food, and internet — how they develop, how they stabilize, and most of all how the same or at least overlapping brain changes underlie them all. And here’s the clincher: I’m going to show you, as I continue to digest it myself, how similar ALL addictions are. When it comes to substance addictions versus behavioural addictions, there’s just not much difference in what the brain is doing.

food, and internet — how they develop, how they stabilize, and most of all how the same or at least overlapping brain changes underlie them all. And here’s the clincher: I’m going to show you, as I continue to digest it myself, how similar ALL addictions are. When it comes to substance addictions versus behavioural addictions, there’s just not much difference in what the brain is doing.

So, it might seem counterintuitive, but heroin addicts, codependent partners, gaming addicts, and sex addicts are very, very much alike. In other words, you don’t have to be a heroin addict or an alcoholic to wreck your life. You can wreck it just as well by spending 18 hours a day on the internet, while the bills pile up, the unemployment cheques fizzle out (and you didn’t notice), and your wife starts packing, not only her stuff but the kids’ stuff too. You might reply: yeah, sure, but substance addiction can kill you! Behavioral addiction? That’s pretty wimpy in comparison. If you believe that, as I did until yesterday, I’ve got news for you. According to the stats, obesity (a result of food addiction) causes 4 – 5 times more “preventable deaths” in the U.S. than the number caused by alcohol.

The conference just ended. I’m going to go out and check on Budapest now — gaze at statues and absorb some culture. But stay tuned for a deeper look at the core processes underlying behavioral and substance addictions — in other words all addictions. Coming up next.

genius. He was the first (as far as I know) to develop a “talking cure” for serious emotional difficulties, and he was the first to bring the idea of unconscious wishes and motives into public parlance. Sure,

genius. He was the first (as far as I know) to develop a “talking cure” for serious emotional difficulties, and he was the first to bring the idea of unconscious wishes and motives into public parlance. Sure,  psychoanalysis — on the couch, four times a week, for fifteen years (?!) — hasn’t lived up to expectations, and I believe it’s correctly pushed aside by more focused, present-tense-oriented, and evidence-based treatment models.

psychoanalysis — on the couch, four times a week, for fifteen years (?!) — hasn’t lived up to expectations, and I believe it’s correctly pushed aside by more focused, present-tense-oriented, and evidence-based treatment models. with a capital S is to be our lodestone, then psychoanalysis doesn’t look so hot either. But, okay, Dodes is inspiring, he’s developed his methods over decades, he’s come

with a capital S is to be our lodestone, then psychoanalysis doesn’t look so hot either. But, okay, Dodes is inspiring, he’s developed his methods over decades, he’s come  problems in the light of one’s early development. A realistic and increasingly popular spin-off of this position is the emphasis on childhood trauma, most famously highlighted by

problems in the light of one’s early development. A realistic and increasingly popular spin-off of this position is the emphasis on childhood trauma, most famously highlighted by  There are addiction treatment centres (e.g.,

There are addiction treatment centres (e.g.,  offers a harm-reduction approach that has psychodynamic psychology (and thus individual psychotherapy) built into it. I particularly like Tatarsky’s model (I spoke there and met him last June) because it is fundamentally empathic and humanistic, honouring individual differences and working with them.

offers a harm-reduction approach that has psychodynamic psychology (and thus individual psychotherapy) built into it. I particularly like Tatarsky’s model (I spoke there and met him last June) because it is fundamentally empathic and humanistic, honouring individual differences and working with them. What’s most interesting to me is how psychodynamic ideas provide a foundation underlying many current schools of psychotherapy. With respect to addiction, ACT and IFS (my favourites — see last post) are all about bringing the past into the present and dealing with it. What seems to be missing from our lives? When did that start? Where does the depression come from? What messages do we repeatedly give ourselves that make us feel hopeless or despicable, so there seems little opportunity for relief except our addiction? Where do contradictory self-statements, like yes, this is what I want and I hate doing this! actually come from?

What’s most interesting to me is how psychodynamic ideas provide a foundation underlying many current schools of psychotherapy. With respect to addiction, ACT and IFS (my favourites — see last post) are all about bringing the past into the present and dealing with it. What seems to be missing from our lives? When did that start? Where does the depression come from? What messages do we repeatedly give ourselves that make us feel hopeless or despicable, so there seems little opportunity for relief except our addiction? Where do contradictory self-statements, like yes, this is what I want and I hate doing this! actually come from? psychotherapists do, is blend different approaches, revising and refining our methods until we find what works best. And what works best appears at the interface of our own personality and knowledge base, our style of connecting with others, and the particular problems (in my case, mostly addiction) that come our way.

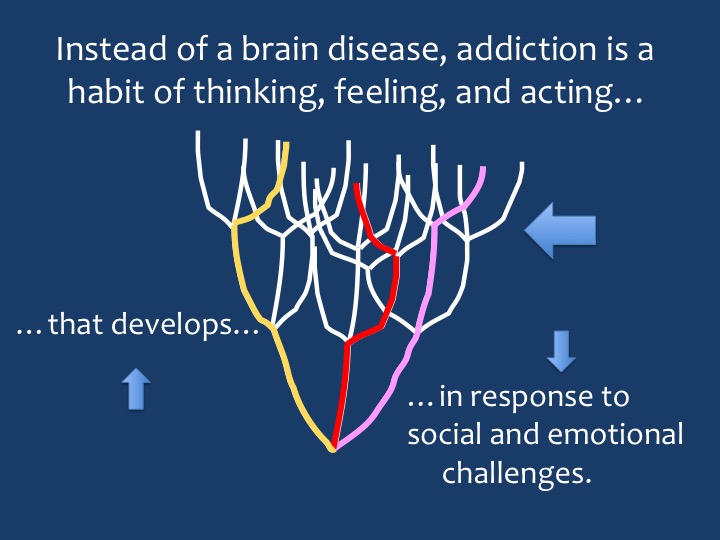

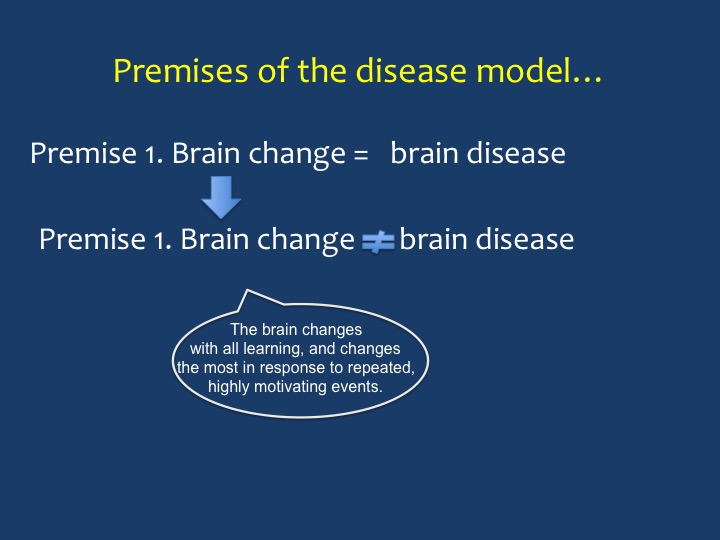

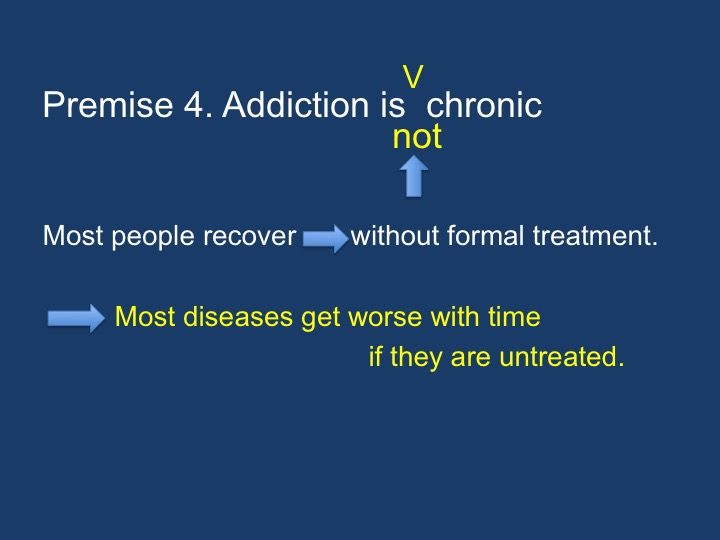

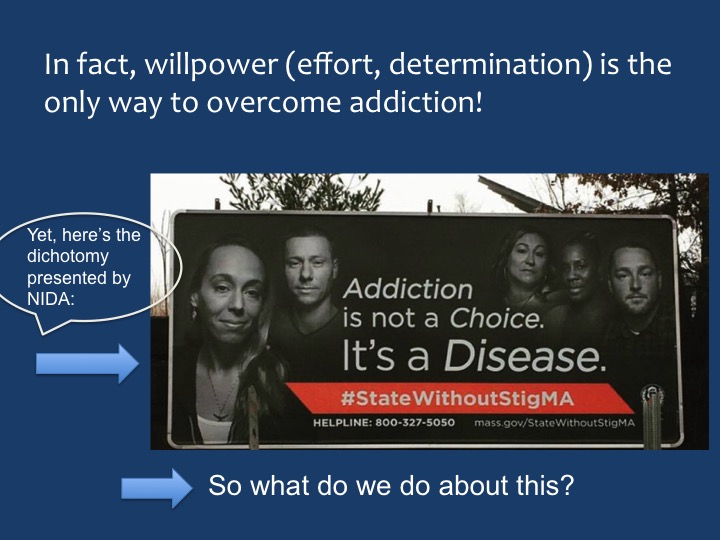

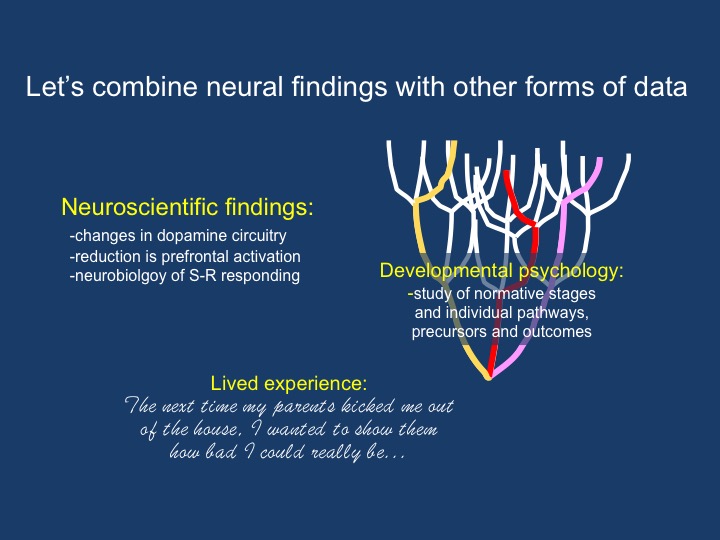

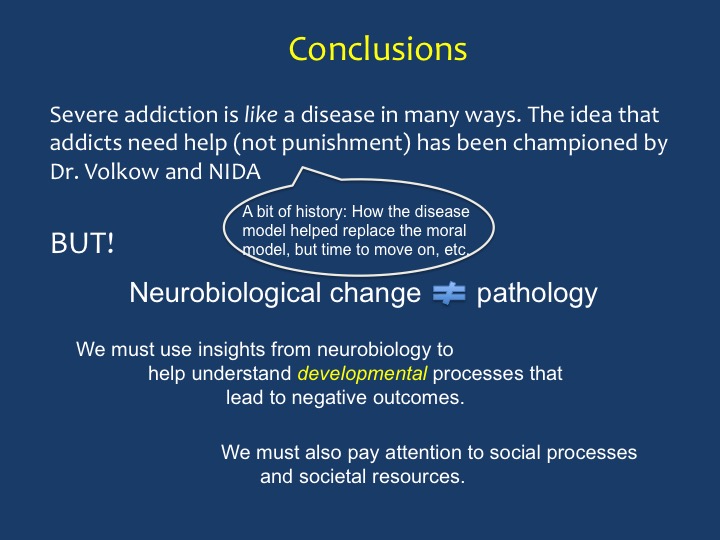

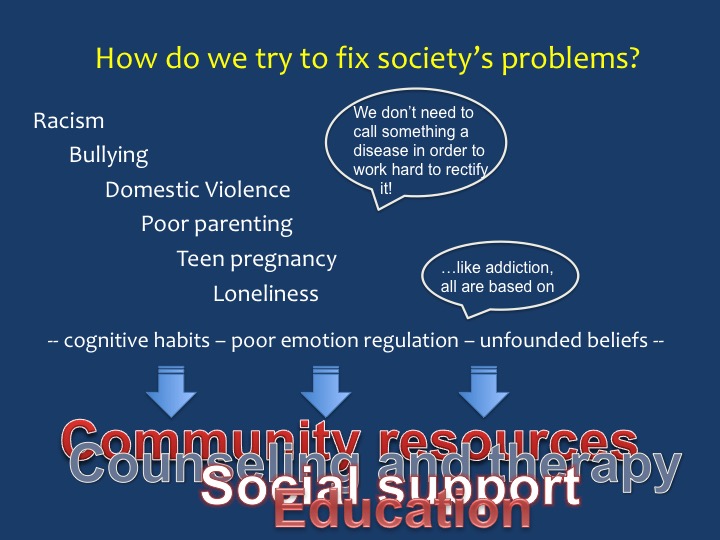

psychotherapists do, is blend different approaches, revising and refining our methods until we find what works best. And what works best appears at the interface of our own personality and knowledge base, our style of connecting with others, and the particular problems (in my case, mostly addiction) that come our way. It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below.

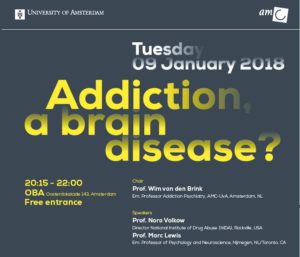

It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below. It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay.

It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay. So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.

So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.

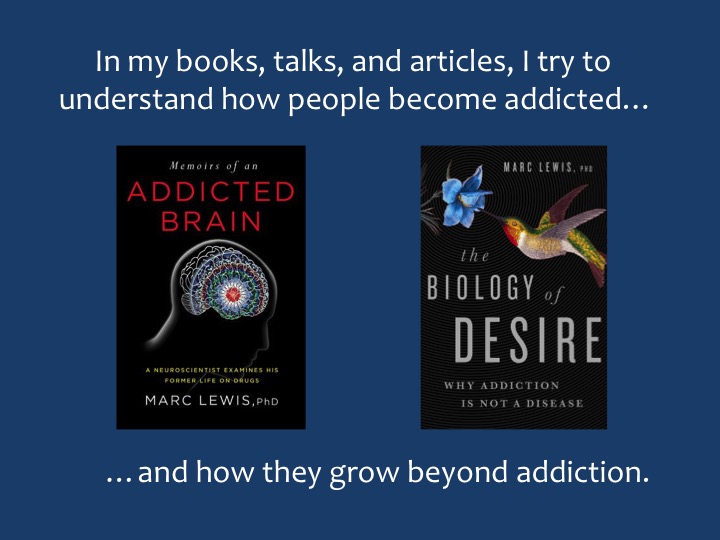

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments