Untangling the confusion between the “opioid crisis” and the overdose epidemic

Hi all. I haven’t been blogging for a while, partly because I wasn’t sure I had anything new to say. But the “opioid crisis” is obviously on everyone’s mind. So, I wanted to get the facts straight, and I pitched an article to The Guardian, published yesterday, based on what I found.

The response has been slightly overwhelming: more than 500 published comments in less than 24 hours (plus some emails to me personally). Most moving to me is the gratitude expressed by people in serious pain, people whose access to needed medication is being quickly cut off by the hysteria concerning the overdose epidemic. The point of my article was that most of the opioid panic is fueled by a misguided perception that opioid pharmaceuticals, prescribed and taken by patients in pain, is this diabolical force behind the wave of deaths.

I am in no way minimizing the tragedy of the overdose epidemic. But as most of you know, fentanyl and its analogues are the primary cause. But here — I’m pasting the article below, with a few additional thoughts, plus a graph from the NIH/NIDA website that helps tell the story. Or read the article in The Guardian and peruse the comment section. There’s a lot of painful reality (plus a lot of stupidity, as usual) revealed by these comments. Makes me feel good about what I wrote.

Pasted from The Guardian:

“The news media is awash with hysteria about the opioid crisis (or opioid epidemic). But what exactly are we talking about? If you Google “opioid crisis”, nine times out of 10 the first paragraph of whatever you’re reading will report on death rates. That’s right, the overdose crisis.

For example, the lead article on the “opioid crisis” on the US National Institutes of Health website begins with this sentence: “Every day, more than 90 Americans die after overdosing on opioids.”

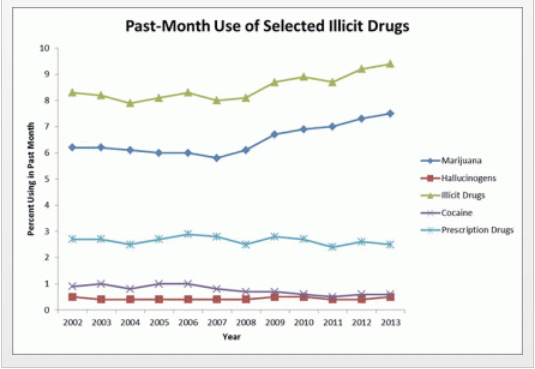

Is the opioid crisis the same as the overdose crisis? No. One has to do with addiction rates, the other with death rates. And addiction rates aren’t rising much, if at all, except perhaps among middle-class whites. [See graph pasted below.] [And note that I should probably have added middle-aged middle-class whites.]

Let’s look a bit deeper.

The overdose crisis is unmistakable. I reported on some of the statistics and causes in the Guardian last July. I think the most striking fact is that drug overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. Some people swallow, or (more often) inject, more opioids than their body can handle, which causes the breathing reflex to shut down. But drug overdoses that include opioids (about 63%) are most often caused by a combination of drugs (or drugs and alcohol) and most often include illegal drugs (eg heroin). When prescription drugs are involved, methadone and oxycontin are at the top of the list, and these drugs are notoriously acquired and used illicitly.

Yet the most bellicose response to the overdose crisis is that we must stop doctors from prescribing opioids. Hmmm.

Yes, there has been an upsurge in the prescription of opioids in the US over the past 20 to 30 years (though prescription rates are currently decreasing). This was a response to an underprescription crisis. Severe and chronic pain were grossly undertreated for most of the 20th century. Even patients dying of cancer were left to writhe in pain until prescription policies began to ease in the 70s and 80s. The cause? An opioid scare campaign not much different from what’s happening today. (See Dreamland by Sam Quinones for details.) [I’ve updated this link.]

Certainly some doctors have been prescribing opioids too generously, and a few are motivated solely by profit. But that’s a tiny slice of the big picture. A close relative of mine is a family doctor in the US. He and his colleagues are generally scared (and angry) that they can be censured by licensing bodies for prescribing opioids to people who need them. And with all the fuss in the press right now, the pockets of overprescription are rapidly disappearing.

[I should probably have mentioned that advertising by Big Pharma also helped fuel the overprescription trend. But that’s kinda old news.]

But the news media rarely bother to distinguish between the legitimate prescription of opioids for pain and the diverting (or stealing) of pain pills for illicit use. The statistics most often reported are a hodge-podge. Take the first sentence of an article on the CNN site posted on 29 October: “Experts say the United States is in the throes of an opioid epidemic, as more than two million of Americans have become dependent on or abused prescription pain pills and street drugs.”

First, why not clarify that most of the abuse of prescription pain pills is not by those for whom they’re prescribed? Among those for whom they are prescribed, the onset of addiction (which is usually temporary) is about 10% for those with a previous drug-use history, and less than 1% for those with no such history. [Thanks to Maia Szalavitz for highlighting these statistics.] Note also the oft-repeated maxim that most heroin users start off on prescription opioids. Most divers start off as swimmers, but most swimmers don’t become divers.

Second, wouldn’t it be sensible for the media to distinguish street drugs such as heroin from pain pills? We’re talking about radically different groups of users.

Third, virtually all experts agree that fentanyl and related drugs are driving the overdose epidemic. These are many times stronger than heroin and far cheaper, so drug dealers often use them to lace or replace heroin. Yet, because fentanyl is a manufactured pharmaceutical prescribed for severe pain, the media often describe it as a prescription painkiller – however it reaches its users.

It’s remarkably irresponsible to ignore these distinctions and then use “sum total” statistics to scare doctors, policymakers and review boards into severely limiting the prescription of pain pills.

By the way, if you were either addicted to opioids or needed them badly for pain relief, what would you do if your prescription was abruptly terminated? Heroin is now easier to acquire than ever, partly because it’s available on the darknet and partly because present-day distribution networks function like independent cells rather than monolithic gangs – much harder to bust. And, of course, increased demand leads to increased supply. Addiction and pain are both serious problems, serious sources of suffering. If you were afflicted with either and couldn’t get help from your doctor, you’d try your best to get relief elsewhere. And your odds of overdosing would increase astronomically.

[A note to my readers: As you see, I’ve mentioned but somewhat underplayed the needs of people in addiction. Knowing my history and my sympathies, I think you must realize that I care very much about their needs as well.]

It’s doctors – not politicians, journalists, or professional review bodies – who are best equipped and motivated to decide what their patients need, at what doses, for what periods of time. And the vast majority of doctors are conscientious, responsible and ethical.

Addiction is not caused by drug availability. The abundant availability of alcohol doesn’t turn us all into alcoholics. No, addiction is caused by psychological (and economic) suffering, especially in childhood and adolescence (eg abuse, neglect, and other traumatic experiences), as revealed by massive correlations between adverse childhood experiences and later substance use. The US is at or near the bottom of the developed world in its record on child welfare and child poverty. No wonder there’s an addiction problem. And how easy it is to blame doctors for causing it.”

Here’s that graph that I should have pasted into the article, if I’d gotten permission and so forth. Note the almost steady rate of illicit drug use since 2002:

Pasted from a page on the NIH/NIDA website.

and use. You should just give up and settle for less, because this isn’t gonna get any better. Besides, nobody will know…or care.

and use. You should just give up and settle for less, because this isn’t gonna get any better. Besides, nobody will know…or care. One of the Trumpocalypse’s unintended contributions to the rational world was the reminder that not everything we hear on the news is real. Neither is everything we hear in our heads — especially the automatic negative thoughts blaring from our own fake news channel.

One of the Trumpocalypse’s unintended contributions to the rational world was the reminder that not everything we hear on the news is real. Neither is everything we hear in our heads — especially the automatic negative thoughts blaring from our own fake news channel. I’ve noticed that, when I was an in-patient or in a treatment program, the fake news network stopped broadcasting, or at least I couldn’t pick it up. I was always puzzled that whenever I was in treatment, I’d do great. Just being there sharpened my awareness. When I came out I’d go along great for a while and then tank. One likely reason: my fake news sources were back in action, broadcasting loud and clear.

I’ve noticed that, when I was an in-patient or in a treatment program, the fake news network stopped broadcasting, or at least I couldn’t pick it up. I was always puzzled that whenever I was in treatment, I’d do great. Just being there sharpened my awareness. When I came out I’d go along great for a while and then tank. One likely reason: my fake news sources were back in action, broadcasting loud and clear. Fake news triggers urges, and vice versa. The satellite feed for the lead story originated long ago and far away — for some of us the stories started in early childhood. The stories can be as incessant as muzak playing over and over in your head. We have to change the channel to stay ahead of it…to stay in front of the fuck-its. Because when do the fuck-its happen? When terrorists demand action, now — no time to stop and think — or else.

Fake news triggers urges, and vice versa. The satellite feed for the lead story originated long ago and far away — for some of us the stories started in early childhood. The stories can be as incessant as muzak playing over and over in your head. We have to change the channel to stay ahead of it…to stay in front of the fuck-its. Because when do the fuck-its happen? When terrorists demand action, now — no time to stop and think — or else. Fake news is now not only a meme but an apt tag for the harmful diatribes that go off in our heads and often drive our behavior. But if we can recognize them, we can label them, and if we can label them, we can stop listening. If we can slow down enough to classify the news as real or fake, then, if it’s fake, we can turn down the volume — all the way down.

Fake news is now not only a meme but an apt tag for the harmful diatribes that go off in our heads and often drive our behavior. But if we can recognize them, we can label them, and if we can label them, we can stop listening. If we can slow down enough to classify the news as real or fake, then, if it’s fake, we can turn down the volume — all the way down. prescriptions for methadone, counselling, and a place to hang out for a little while.

prescriptions for methadone, counselling, and a place to hang out for a little while. a staff person present, just being friendly, chatting, offering snacks. The staff consists of two social workers, two MA level psychologists, a criminologist (to help with charges, probation, as so forth), and the doctor, Carl, who wrote the methadone prescriptions. Carl was my host.

a staff person present, just being friendly, chatting, offering snacks. The staff consists of two social workers, two MA level psychologists, a criminologist (to help with charges, probation, as so forth), and the doctor, Carl, who wrote the methadone prescriptions. Carl was my host. (in exchange for used needles) — I mostly sat in a chair next to Carl in an office/interview room, while one client after another came for their methadone script. It was sort of fascinating.

(in exchange for used needles) — I mostly sat in a chair next to Carl in an office/interview room, while one client after another came for their methadone script. It was sort of fascinating. in the chair across from the doc. They often looked defeated and helpless. While some expressed enthusiasm, plans for the future, many looked dreamy or blank. Quite a few had the hunched over posture that expresses shame or remorse. Their eye contact might be sparse and fleeting, looking down a lot — the gaze pattern of people who live with a chronic level of shame or sense of inferiority. A sense of personal failure they’ve grown deeply accustomed to.

in the chair across from the doc. They often looked defeated and helpless. While some expressed enthusiasm, plans for the future, many looked dreamy or blank. Quite a few had the hunched over posture that expresses shame or remorse. Their eye contact might be sparse and fleeting, looking down a lot — the gaze pattern of people who live with a chronic level of shame or sense of inferiority. A sense of personal failure they’ve grown deeply accustomed to. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments