I got back yesterday around noon. What a relief it was to be home! India is overwhelming in so many ways, with poverty and raw need topping the list. To get back to this calm, orderly place was a reprieve and a pleasure, tinged with guilt at leaving all that suffering behind.

For anyone just tuning in now, I was at a week-long “dialogue” with the Dalai Lama on the theme of “Desire, craving, and addiction.” I was one of eight presenters, each of whom gave a talk to His Holiness (as he is called) and to the surrounding experts, monks, movie stars and what have you. All the talks are posted here. My talk is here. I want to tell you about two of the talks I found most fascinating and most relevant for people struggling with addiction.

The first was by Matthieu Ricard. This guy is amazing, He’s a Frenchman turned Buddhist monk for the last 20 years or so. He has a shaven head, glasses, and eyes that are kind and beaming with intelligence. And he’s humorous, human, and incredibly knowledgable at the same time. He just finished a thousand-page (!) book on altruism, he’s very close to His

The first was by Matthieu Ricard. This guy is amazing, He’s a Frenchman turned Buddhist monk for the last 20 years or so. He has a shaven head, glasses, and eyes that are kind and beaming with intelligence. And he’s humorous, human, and incredibly knowledgable at the same time. He just finished a thousand-page (!) book on altruism, he’s very close to His  Holiness and sees him often, he’s participated in studies of brain states related to meditation, and he says his favourite thing to do is retreat to his retreat in the Himalayas — where he meditates all day long and essentially alone (there are a few other monks around, but they don’t talk to each other). Yet he spends most of his time running the Karuna-Shechen organization, which has established roughly 140 projects aimed at improving the lives of children in Tibet, Nepal and India. Please check out his talk. Or, if you don’t have time at the moment, here’s a summary:

Holiness and sees him often, he’s participated in studies of brain states related to meditation, and he says his favourite thing to do is retreat to his retreat in the Himalayas — where he meditates all day long and essentially alone (there are a few other monks around, but they don’t talk to each other). Yet he spends most of his time running the Karuna-Shechen organization, which has established roughly 140 projects aimed at improving the lives of children in Tibet, Nepal and India. Please check out his talk. Or, if you don’t have time at the moment, here’s a summary:

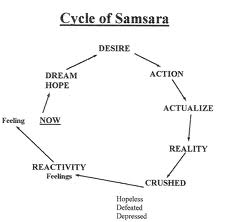

Matthieu talked about the elements of Buddhism and general mindfulness (including but not limited to meditation) that can be of practical use to recovering addicts — or addicts who are trying to quit. He talks about the roots of suffering in our determined, unshakable view of ourselves as the center of the universe. That’s the primary delusion. And it requires us to be constantly protecting, improving, and caring for this self — this selfish self. In fact we’re willing to give up our freedom and control, just to continue to feed this self with drugs, booze, or whatever we think will protect it.

Matthieu recognizes the fundamental importance of craving in addiction. Craving and attachment. Here are his three suggestions for getting on top of it:

1. Apply a direct antidote: Find a mental state that is incompatible with craving. That is, focus and/or meditate on the unattractive qualities of the thing you’re addicted to. For example, focus on freedom, which is directly incompatible with the out-of-controlness provided by the addictive substance. Or maybe focus on the anxiety that accompanies withdrawal and on how that anxiety creeps in, even while we’re high and supposed to be having fun.

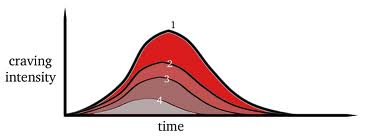

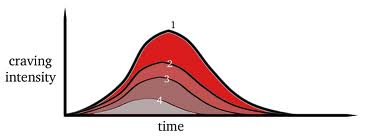

2. Examine the nature of craving itself: The fact that you’re craving doesn’t mean that’s all there is going on in you. Since you are aware of your craving, there must be a part of you that is outside the craving, looking in. By continuing to experience this awareness, through mindfulness or simply reflection, that part of you — the part that is outside the craving — will continue to grow. While you are looking at the craving, you will notice that, yes, it’s strong, but it is just a feeling, it comes and goes, there is nothing permanent of concrete about it. So you don’t have to obey it after all.

3. Use craving as a catalyst: This may be the most difficult, says Matthieu, but it can work for some people. There is a feeling of strong clarity that comes with the onset of craving. Stay with that feeling. It is a version of your energy, your wish for betterment. Go with that momentum in a direction that’s opposite to what we normally do. Use it to strive for betterment rather than relief. Easier said than done, he admits. So are the other two suggestions. But they can work.

Matthieu concludes that the cumulative nature of addiction, building on itself over time, means you can’t stop on a dime. It took time to build up this habit. It will take time, and effort, to overcome it. But how do you find the motivation to change? This is a tough one. He says: look for it in the way you’d look for inspiration. You try different environments, find different people to talk with. He even talks about the role of neuroplasticity in shaping both the habit and its undoing. It’s good to listen to him talk. His humility comes out in recognizing that these ideas are not directly translatable into clinical methods. Yet they are strong ideas, and that gap is waiting to be filled. That’s where Sarah Bowen comes in.

She was the last speaker of the week, and she and I agreed that we liked being the bookends — the conference starting with me and ending with her. My talk mostly posed the problem, hers, the solution. Without the need of concepts such as disease or brain hijacking to thoroughly address addiction and recovery.

Sarah Bowen is focused and rational. A good listener and a sharp thinker. She’s attractive, 30-something, and nothing resembling a Buddhist monk (or nun). She’s a clinical scientist devoted to the development of Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP), the first and only treatment approach that is built around mindfulness training. Sarah inherited this nascent program from her mentor, Alan Marlatt. But she is taking it to new heights, I think, and conducting well-controlled outcome studies to prove it. Here is Sarah’s talk. And here’s my summary:

Sarah Bowen is focused and rational. A good listener and a sharp thinker. She’s attractive, 30-something, and nothing resembling a Buddhist monk (or nun). She’s a clinical scientist devoted to the development of Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP), the first and only treatment approach that is built around mindfulness training. Sarah inherited this nascent program from her mentor, Alan Marlatt. But she is taking it to new heights, I think, and conducting well-controlled outcome studies to prove it. Here is Sarah’s talk. And here’s my summary:

MBRP is modeled on Jon Kabat-Zinn’s very effective programs for stress reduction, recovery from depression, and coping with chronic pain. This is where East meets West with a bang, generating success after success where Western psychiatry was left flailing. The program Sarah has developed uses group process (and the sense of companionship it entails) to take addicts through orderly steps of training in mindfulness, awareness, and self-compassion. This link is intended for clinicians but it provides MP3 instructions on each of the steps. Very helpful! The goal is not to get rid of craving but to be aware of it, understand it, see through it, and move beyond it. As a bonus prize, people who go through the program actually report a reduction in the intensity of craving as well as a drop (or cessation) in substance use. And these outcome statistics are gathered through well-controlled, scientifically valid studies.

Skills for tuning your attention, letting craving come and go, relaxing in response to stress, and talking to yourself in a more compassionate way are methodically developed through a series of exercises, performed by each individual in the group context (over an eight-week period) and guided by a moderator who is already advanced in her own mindfulness practice. A compelling example is “urge-surfing,” a mind-set that allows you to coexist with your cravings in an almost playful way, moment by moment, while staying upright. Then these skills are systematically brought to bear on life outside the treatment setting — so they can be accessed when it counts most, when you’re home alone at night or  whenever and wherever you’re at your most vulnerable. I can’t provide more detail in this summary, but I urge you to check out the talk. Not only does MBRP translate Matthieu’s ideas into concrete practices, but it is shown to be far more effective than other treatment approaches — even for people who have bottomed out in their lifestyle or…their lack of a lifestyle. When asked to suggest a treatment course for addicts, this is the program I’d feel most confident recommending — if only it were available more widely. Maybe some day it will be.

whenever and wherever you’re at your most vulnerable. I can’t provide more detail in this summary, but I urge you to check out the talk. Not only does MBRP translate Matthieu’s ideas into concrete practices, but it is shown to be far more effective than other treatment approaches — even for people who have bottomed out in their lifestyle or…their lack of a lifestyle. When asked to suggest a treatment course for addicts, this is the program I’d feel most confident recommending — if only it were available more widely. Maybe some day it will be.

That’s enough for this very long post. I have more to tell. I didn’t even get to the neuroscience presentations, nor the string of objections Nora Volkow voiced in response to my (you guessed it) contention that addiction is NOT a disease. Nor the singular perspective offered by the Dalai Lama himself. Coming soon…

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica.

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica. The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain.

The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain. defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning!

defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning! at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

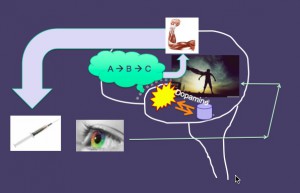

person thinks familiar thoughts or performs familiar actions, a vast number of synapses become activated in predictable – ie, habitual – configurations. Patterns of neural firing in one region become synchronised with patterns of firing in other regions, and that helps the participating synapses form these habitual connections.

person thinks familiar thoughts or performs familiar actions, a vast number of synapses become activated in predictable – ie, habitual – configurations. Patterns of neural firing in one region become synchronised with patterns of firing in other regions, and that helps the participating synapses form these habitual connections. synapses with which they’re connected, and because connections between brain cells are almost always reciprocal (two-way), the reinforcing activation is returned. Thus, repeated patterns of neural activation are self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing: they form circuits or pathways with an increasing probability of ‘lighting up’ whenever certain cues or stimuli (or thoughts or memories) are encountered. According to Hebb’s rule: ‘Cells that fire together, wire together.’

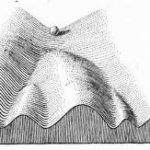

synapses with which they’re connected, and because connections between brain cells are almost always reciprocal (two-way), the reinforcing activation is returned. Thus, repeated patterns of neural activation are self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing: they form circuits or pathways with an increasing probability of ‘lighting up’ whenever certain cues or stimuli (or thoughts or memories) are encountered. According to Hebb’s rule: ‘Cells that fire together, wire together.’ attractor: the tree acquires a shape. Birds fly in sync with each other and form a V-shaped (or other-shaped) flock. Ecosystems go through periods of massive change (eg, speciation and species death) and then stabilise. Cities stabilise. Cultures stabilise. Even family dynamics stabilise. Family arguments inevitably fall back into the same infuriating script.

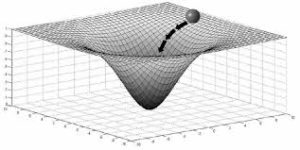

attractor: the tree acquires a shape. Birds fly in sync with each other and form a V-shaped (or other-shaped) flock. Ecosystems go through periods of massive change (eg, speciation and species death) and then stabilise. Cities stabilise. Cultures stabilise. Even family dynamics stabilise. Family arguments inevitably fall back into the same infuriating script. system in place? Attractors are often portrayed as valleys or wells on a flat surface, that surface representing many possible states for the system to occupy. The system, the person, can then be seen as a marble rolling around on this surface of possibilities until it rolls into an attractor well. And then it’s hard for it to roll back out. Physicists will say that the system requires extra energy to push itself out of its attractor. The analogy in human development might be the effort people require to shift out of a particular pattern of thinking or acting.

system in place? Attractors are often portrayed as valleys or wells on a flat surface, that surface representing many possible states for the system to occupy. The system, the person, can then be seen as a marble rolling around on this surface of possibilities until it rolls into an attractor well. And then it’s hard for it to roll back out. Physicists will say that the system requires extra energy to push itself out of its attractor. The analogy in human development might be the effort people require to shift out of a particular pattern of thinking or acting. In human development, normative achievements can be seen as attractors. These might include learning to be a competent language user, or falling in love and having kids. But individual personality development can also be described in terms of attractors – recognisable features that characterise the individual in a particular way. And these features can be seen to branch out with development and form ruts — ruts that can remain in place for a long time.

In human development, normative achievements can be seen as attractors. These might include learning to be a competent language user, or falling in love and having kids. But individual personality development can also be described in terms of attractors – recognisable features that characterise the individual in a particular way. And these features can be seen to branch out with development and form ruts — ruts that can remain in place for a long time.

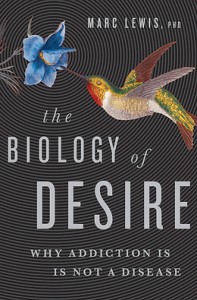

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments