Travel and trust

Hello! It’s been awhile. This is vacation time in the Netherlands. The kids are out of school for two weeks and we’re trying to do family-type things. I know, it’s a strange time to vacate, but the weather here is so spotty, this might be one of the few periods likely to get some sun and warmth.

So I thought! Last Saturday we rented a boat. A very large boat (11.5 meters/ about 38 feet) with cabins below deck and all that, and the four of us set off from a town called Sneek (pronounced Snake). Well named, because the waterways leading out of the harbour were so incredibly narrow and sinewy that  we got lost before we ever got to the main canal. Ended up in some cul-de-sac where an irate man with a house on the water kept waving us away. That’s because we kept almost ramming his house, which was very close to the shore. We were trying to make a U-turn in a narrow spot — just about impossible, especially because I had not yet discovered the “bow-thrusters” among the many Dutch-named switches on the instrument panel. When he finally realized that we didn’t understand a word he was saying, he started again in English: “Practice!” he yelled. “Go on the lake and practice!” Yes, yes, an obvious suggestion. If only we could find the lake.

we got lost before we ever got to the main canal. Ended up in some cul-de-sac where an irate man with a house on the water kept waving us away. That’s because we kept almost ramming his house, which was very close to the shore. We were trying to make a U-turn in a narrow spot — just about impossible, especially because I had not yet discovered the “bow-thrusters” among the many Dutch-named switches on the instrument panel. When he finally realized that we didn’t understand a word he was saying, he started again in English: “Practice!” he yelled. “Go on the lake and practice!” Yes, yes, an obvious suggestion. If only we could find the lake.

Anyway, we had a lot of fun. Isabel and I mostly sitting up on the top deck sharing a big steering wheel, watching the cows and sheep going by, and the boys down below, playing cards, with occasional sojourns to the upper deck to help steer. As I am constantly reminded, seven-year-olds don’t want to watch; they want to do. But it was cold out! Polar winds blowing through us except when we were huddled under this massive flapping plastic tarp. Oh well, it was still great, and we didn’t hit a thing in four days. Well maybe just a few tiny bumps. Tiny!

Anyway, we had a lot of fun. Isabel and I mostly sitting up on the top deck sharing a big steering wheel, watching the cows and sheep going by, and the boys down below, playing cards, with occasional sojourns to the upper deck to help steer. As I am constantly reminded, seven-year-olds don’t want to watch; they want to do. But it was cold out! Polar winds blowing through us except when we were huddled under this massive flapping plastic tarp. Oh well, it was still great, and we didn’t hit a thing in four days. Well maybe just a few tiny bumps. Tiny!

Isabel and I are going to drive over to France in a couple of days. It’s only a few hours, and it’s worth it just for the food. But meanwhile I have two talks to prepare, and one of them is a TED talk. Yes, TED! I was invited to join this TEDx event held at my university, and I’m getting pretty jazzed about it. The theme of the conference is “trust,” so naturally my talk will be about trust and addiction.

At first, I wasn’t sure how to approach this topic. You can’t trust an addict, right? How do you know an addict is lying? Because his lips are moving… Hah hah. No, wait a minute, how about…addicts can’t trust the treatment community? We know that people are almost always let down by their experiences in rehab, whether in- or out-patient, and so much of the treatment world is dominated by 12-step philosophy, which is certainly not for everyone (right, Persephone?), and a 30-day stint of treatment is about as useful as a bath during a dust storm, and the revolving door of addicts coming in and out is closely matched by that of the treatment staff, who come and go at an alarming rate themselves, and most of whom really don’t have the knowledge or the credentials to help people in serious trouble. The general public can’t trust addicts, addicts can’t trust public institutions..etc, etc… Could that work?

But is seemed a bit superficial, a bit too obvious, no real bite to it. And then, about two weeks ago, it hit me: The main issue with trust and addiction is that addicts can’t trust themselves. Of course! You can’t trust yourself to take care of yourself. Because, when you tell yourself you’re going to stop, or at least slow down, or at least stop injecting, or whatever it is, and swear up and down that this time is the LAST time, and it will NOT happen again….you end up betraying yourself. Time and time again. Why would you trust yourself after you’ve let yourself down 50 or 500 times?! But it’s worse than that: you hardly even have a self to trust. You (or I) lose the sense of a grown-up conscientious self that can soothe you, hold you, get you through the rough times, tell you that it’s just craving and it will not last forever… That self is so damned hard to find after a while that you stop believing it exists. No, you can’t trust yourself. (And surely, as a consequence, no one else can trust you either.) So who/what do you end up trusting? Your addiction, of course! You trust that a hit of smack or a bottle of vodka or a few grams of coke or yet another roller-coaster ride of sex or gambling or that bowl of chocolate ice-cream or even the glazed eye of your computer screen will make you feel better. At least for a while. And it might. For a while. We put our trust in the thing we’re addicted to…because there is no one and nothing else to trust. And of course, of course, each time we do that, we lose even more ground with our self. The ability to trust ourself takes yet another soul-crushing hit. Vicious circle. And how.

This TED talk thing makes me nervous. I have to stand on a stage in front of 1,200 people, knowing that every move I make, every sound I utter, will appear on computer screens all over the world and become inscribed in the holy scrolls of YouTube for time immemorial. With no notes! No powerpoint slides at my fingertips to remind me of what I’m trying to say. Not even a podium to hide behind. Scary!

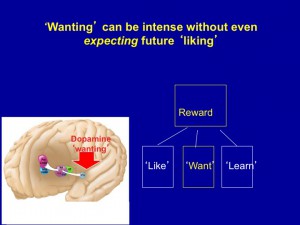

But I think I have a good talk. I’m going to present two psychological phenomena that make it particularly hard for addicts to trust themselves: ego fatigue (see previous posts) and delay discounting (the tendency to place way too much value on immediate rewards, at the expense of long-terms gains….like, oh, keeping your marriage or your job intact — a result of that dopamine/craving wave). I’ve got it down in my head, why these phenomena stack the deck against us. And why that makes it just so hard to quit. I’ve practiced it in the car. And once in front of Isabel. It’s going to be good.

And I’m going to practice it with you. Next post. Stay tuned.

Ben seems to be trying with great determination to keep away from drugs. Yet the demon of addiction is doing pushups in the parking lot, just as they warn at the 12-step meeting he attends with his mom. He finds a bag of dope in the attic, but manages to avoid taking it and gives it to his mother instead. He looks the other way when dealers and drug buddies from his former life show up magically on elevators and at car windows.

Ben seems to be trying with great determination to keep away from drugs. Yet the demon of addiction is doing pushups in the parking lot, just as they warn at the 12-step meeting he attends with his mom. He finds a bag of dope in the attic, but manages to avoid taking it and gives it to his mother instead. He looks the other way when dealers and drug buddies from his former life show up magically on elevators and at car windows.  He bravely endures the cultural ambiguity of an American Christmas and tries his best to connect with his sibs and step-sibs. He’s a good guy, and he fights the good fight, but…well I don’t want to spoil it in case you decide to watch it.

He bravely endures the cultural ambiguity of an American Christmas and tries his best to connect with his sibs and step-sibs. He’s a good guy, and he fights the good fight, but…well I don’t want to spoil it in case you decide to watch it. Instead, the usual “Reader’s Digest” simplifications are offered. For example, Mom meets the doctor who first prescribed pain pills, which got Ben “hooked” years ago, and says she hopes he dies a horrible death. We know that the OxyContin surge in the 80’s and 90’s did increase exposure to opiates and fueled increased rates of addiction. But to continue to blame doctors is insane. As

Instead, the usual “Reader’s Digest” simplifications are offered. For example, Mom meets the doctor who first prescribed pain pills, which got Ben “hooked” years ago, and says she hopes he dies a horrible death. We know that the OxyContin surge in the 80’s and 90’s did increase exposure to opiates and fueled increased rates of addiction. But to continue to blame doctors is insane. As  The 12-step presence is portrayed somewhat accurately. Both the good (fellowship, honesty, and mutual respect) and the not-so-good (brain washing, propaganda, and the all-or-none trappings of the disease model) correspond well enough with reality.

The 12-step presence is portrayed somewhat accurately. Both the good (fellowship, honesty, and mutual respect) and the not-so-good (brain washing, propaganda, and the all-or-none trappings of the disease model) correspond well enough with reality. There is some recognition that addicts have choices. Ben fights his impulses bravely, and he makes sensible choices to avoid contact with the people and places that serve as triggers. And yet there is this creepy sense of fatalism sneaking up on Ben and other addicts. As though whatever choices they think they’re making, they’re bound to succumb. By the way, addiction isn’t referred to as “a disease” in this movie. Yet the miasma of an alien presence or infection lurks behind much of the dialogue and plot.

There is some recognition that addicts have choices. Ben fights his impulses bravely, and he makes sensible choices to avoid contact with the people and places that serve as triggers. And yet there is this creepy sense of fatalism sneaking up on Ben and other addicts. As though whatever choices they think they’re making, they’re bound to succumb. By the way, addiction isn’t referred to as “a disease” in this movie. Yet the miasma of an alien presence or infection lurks behind much of the dialogue and plot. Junkies are portrayed as zombies. They are the opposite of clean. They’re dirty. They hover in alleyways, under bridges, around trashcans brimming with burning litter. It’s a classic and grossly overdone stereotype. When I was shooting heroin or morphine in my twenties , garbage-strewn alleys and river banks were not my preferred home away from home.

Junkies are portrayed as zombies. They are the opposite of clean. They’re dirty. They hover in alleyways, under bridges, around trashcans brimming with burning litter. It’s a classic and grossly overdone stereotype. When I was shooting heroin or morphine in my twenties , garbage-strewn alleys and river banks were not my preferred home away from home. But here’s my biggest beef. People who take drugs are shown to be occupied by some demonic force (or disease, or what have you) that makes them another species. They are not anything like normal people. They live in a different world, they’re not to be trusted, and they ought to be sent away to residential rehabs (where they won’t infect the rest of us) until the demon is exorcised — itself a rare event. This dichotomous “us vs them” perspective is the real message of the movie.

But here’s my biggest beef. People who take drugs are shown to be occupied by some demonic force (or disease, or what have you) that makes them another species. They are not anything like normal people. They live in a different world, they’re not to be trusted, and they ought to be sent away to residential rehabs (where they won’t infect the rest of us) until the demon is exorcised — itself a rare event. This dichotomous “us vs them” perspective is the real message of the movie. balance to their lives — what I referred to as “substance” last post. The cause of addiction can be found in mall culture itself (portrayed in the movie as a sort of heaven on earth), the rampant commercialism that sucks meaning out of day-to-day life, the often immutable stamp of privilege vs. poverty and the stultifying dead-end lives of those who don’t make the cut. Not to mention the sheer hypocrisy of a society that proclaims Christian values but rewards self-serving, self-protective priorities. I wonder if Ben was infected by these horrors rather than a magical drug high, and whether that’s what made it so hard for him to quit.

balance to their lives — what I referred to as “substance” last post. The cause of addiction can be found in mall culture itself (portrayed in the movie as a sort of heaven on earth), the rampant commercialism that sucks meaning out of day-to-day life, the often immutable stamp of privilege vs. poverty and the stultifying dead-end lives of those who don’t make the cut. Not to mention the sheer hypocrisy of a society that proclaims Christian values but rewards self-serving, self-protective priorities. I wonder if Ben was infected by these horrors rather than a magical drug high, and whether that’s what made it so hard for him to quit.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments