…by Kate Benet…

Marc here: Perhaps the one question I get asked most often is whether it’s possible to go back to safe use (of alcohol or other substances) after being addicted. So, after reading Kate’s story, please reserve half a minute to read my comments at the end. It seems crucial to embed the diversity of people’s experiences in a general framework that can make sense of them all.

………..

Now, Kate:

Approaching my 25-year anniversary of sobriety in early September 2019, I had thought for weeks, if not months, about whether I could now drink moderately. I had been sober way more years in my life than I had spent drinking (now 57 years old). More importantly, my life in the past 25 years had changed dramatically for the better. I had worked hard for years to create a stable and rewarding life.

I read a lot on the internet about whether moderate drinking was possible after a long abstinence. I read the posts on this blog with great interest. I talked through my thought process with my husband, a normal drinker, and he was supportive of my wish to be able to

I read a lot on the internet about whether moderate drinking was possible after a long abstinence. I read the posts on this blog with great interest. I talked through my thought process with my husband, a normal drinker, and he was supportive of my wish to be able to  enjoy a nice glass of wine or good craft beer now and then. This is what I had missed over the years. Those certain occasions when it is so nice to be able to add alcohol to the experience: a fine dinner or a sunny afternoon relaxing on the porch. He was supportive — whether I had a drink or did not, whether I tried it and continued, or tried it and stopped.

enjoy a nice glass of wine or good craft beer now and then. This is what I had missed over the years. Those certain occasions when it is so nice to be able to add alcohol to the experience: a fine dinner or a sunny afternoon relaxing on the porch. He was supportive — whether I had a drink or did not, whether I tried it and continued, or tried it and stopped.

Last Saturday night I took the plunge and had one glass of red wine. Waves of fear washed over me. The experience was surreal. Who was I? What was this thing that I was doing? The wine tasted fantastic. I could feel the effect but, amazingly, I did not like it. This was in stark contrast to how I used to experience alcohol, thinking the taste wasn’t too bad and the effect itself was incredibly nice.

Last Saturday night I took the plunge and had one glass of red wine. Waves of fear washed over me. The experience was surreal. Who was I? What was this thing that I was doing? The wine tasted fantastic. I could feel the effect but, amazingly, I did not like it. This was in stark contrast to how I used to experience alcohol, thinking the taste wasn’t too bad and the effect itself was incredibly nice.

One week after this experience I can say this. The unleashing of craving from this one drink after 25 years of absolute sobriety was beyond belief. It was like the 25 years had never happened. The portal to a horrible, frightening feeling had been opened. I had the sense of a dual persona hovering at the edges of my life, ready to be activated in full.

One week after this experience I can say this. The unleashing of craving from this one drink after 25 years of absolute sobriety was beyond belief. It was like the 25 years had never happened. The portal to a horrible, frightening feeling had been opened. I had the sense of a dual persona hovering at the edges of my life, ready to be activated in full.

In the days that followed that one drink I was gripped with craving and mental obsession about when I could reasonably have another. When I went to work on Monday, to a challenging job that I enjoyed, in my new “maybe a drinker” mindset, the job felt too hard on many subtle but powerful levels. My feelings towards my husband and my children shifted ever so slightly. I felt annoyance at first, and then a more ominous sense that I would not be willing or able to navigate the nuanced ups and downs that are human relationships.

In the days that followed that one drink I was gripped with craving and mental obsession about when I could reasonably have another. When I went to work on Monday, to a challenging job that I enjoyed, in my new “maybe a drinker” mindset, the job felt too hard on many subtle but powerful levels. My feelings towards my husband and my children shifted ever so slightly. I felt annoyance at first, and then a more ominous sense that I would not be willing or able to navigate the nuanced ups and downs that are human relationships.

No one would be the wiser if I continued along this path. Outwardly it would look the same. I could force my life to keep going. But there was something really wrong with how it felt, to me, internally, at a deep and vivid

No one would be the wiser if I continued along this path. Outwardly it would look the same. I could force my life to keep going. But there was something really wrong with how it felt, to me, internally, at a deep and vivid  level — that this would be a disastrous path. The degree of effort and struggle that would be introduced into my life would be dreadful. That became obvious — painfully obvious.

level — that this would be a disastrous path. The degree of effort and struggle that would be introduced into my life would be dreadful. That became obvious — painfully obvious.

One week later the ripples from throwing that stone in the pond are finally settling down and I know I will never do that again. If there are times in the future that trigger my thoughts about the pleasures of drinking, instead of feeling deprived, I’ll think back on this experiment and I will remember how lucky I am.

Not everyone will have this kind of experience. Some people can drink moderately after a long abstinence. Some will have matured out of the problem. I am just not one of those people. I hope this helps anyone else who is facing the big choice. If you are like me, trying to drink again unleashes a unique sort of hell.

………..

Marc again: When I speak to naive audiences, as I did on Wednesday to a group of college students, I often remark that roughly half of those classed as problem drinkers (those with an “alcohol use disorder” in the current DSM parlance) can return to “social drinking” or “safe” drinking at some point. (There’s plenty of research on this, but perhaps start with James Morris, who specializes in alcohol misuse research and intervention with a harm-reduction focus.) Then, during the Q&A, I often get asked, as I did last week, how to know which side of that 50%-line you (or a loved one) might fall on.

To me, Kate’s tale packs at least two take-home lessons: Lesson 1 is that many people can’t return to controlled/social drinking, so the harm-reduction approach is just wrong for them. And the harm can be insidious. It can start off unconscious and quickly become entrenched. This is of course the nose-dive, we-told-you-so, addiction-doing-push-ups message that AA flaunts unceasingly. And…it just happens to be relevant — for many people. Lesson 2 is that one drink doesn’t usually wreck your life and destroy everything you’ve been working to achieve. In other words, it is possible, and sometimes highly desirable, to examine, to question, and to explore your options — as Kate did. Certainly that is NOT the message we get from AA.

To guide your thinking further on the social issues, psychological issues, and available help associated with Harm Reduction for alcohol, I encourage you to check out HAMS (Harm Reduction, Abstinence, and Moderation Support), founded by Kenneth Anderson, now co-led by April Wilson Smith. Also check out their recent book, a collection of intimate memoirs introduced with a brief but comprehensive overview: BETTER IS BETTER! Stories of Alcohol Harm Reduction. A guest-post by April is coming up soon.

more simply drug seeking — in, for example, crayfish, sea-slugs, something called zebrafish, and the common fruit fly (drosophila). Seriously. They listened to what I said about human addiction. I stressed cognitive-emotional factors like “now appeal” and “ego fatigue”, I stressed how difficult it is to make good decisions in stressful environments, especially when memory serves up powerful associations between getting high and relief. I talked about the symbolic appeal that intensifies addiction for us humans. How we’re addicted to what the drug means to us more than to the physiological change it produces. They listened, but I don’t think they got it. And when it came to my spiel about the internal dialogue, the “addict self” and so on, it’s like we were on different planets.

more simply drug seeking — in, for example, crayfish, sea-slugs, something called zebrafish, and the common fruit fly (drosophila). Seriously. They listened to what I said about human addiction. I stressed cognitive-emotional factors like “now appeal” and “ego fatigue”, I stressed how difficult it is to make good decisions in stressful environments, especially when memory serves up powerful associations between getting high and relief. I talked about the symbolic appeal that intensifies addiction for us humans. How we’re addicted to what the drug means to us more than to the physiological change it produces. They listened, but I don’t think they got it. And when it came to my spiel about the internal dialogue, the “addict self” and so on, it’s like we were on different planets. Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to

Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to  them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by

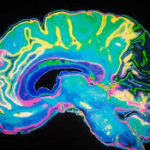

them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by  which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company.

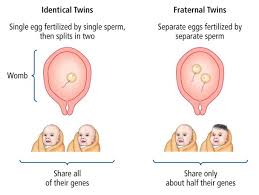

which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company. ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average.

ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average. But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit.

But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit. One of the scientists speaking at the conference,

One of the scientists speaking at the conference,  dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

Doctors are taught from year 1 Medicine (if not before): First, do no harm. And yet, in treating addicted individuals, doctors often do more harm than good — by obstructing or totally derailing the recovery process. That should never happen! I want to show you what I mean by telling you part 2 of Sally’s story —

Doctors are taught from year 1 Medicine (if not before): First, do no harm. And yet, in treating addicted individuals, doctors often do more harm than good — by obstructing or totally derailing the recovery process. That should never happen! I want to show you what I mean by telling you part 2 of Sally’s story —  life on the street. And she tended to obsess about her next dose for too much of her day. She wanted to have done with it. Yet, withdrawing from heroin had been so grueling — it still terrified her. So the solution was obviously to taper gradually.

life on the street. And she tended to obsess about her next dose for too much of her day. She wanted to have done with it. Yet, withdrawing from heroin had been so grueling — it still terrified her. So the solution was obviously to taper gradually. pressing me: let’s go down another two tablets this week. I don’t think I need my second morning dose. She started to skip doses…and that meant she had a reservoir of spares, just in case. She was tailoring it, shaping it, doing it. She was the boss.

pressing me: let’s go down another two tablets this week. I don’t think I need my second morning dose. She started to skip doses…and that meant she had a reservoir of spares, just in case. She was tailoring it, shaping it, doing it. She was the boss. through the very end of her taper and possible withdrawal symptoms — not even 15 or 20 tabs. Valium is very addictive, you know. But that was okay: they’d taper together. She’d come to the office every week — not an easy trek for a mother of three small kids, but it was important for him to see her, to monitor her. And she would reduce her intake by one tablet — 30 mg — at a time, he insisted. But she had to agree that every time she reduced her dose, she’d have to maintain the new level. She couldn’t go back up. Not even for a particularly bad day. He knew what was best for her. Did she agree? Did she have a choice? If she didn’t agree he’d stop her prescription, and then she’d be in danger of paracetamol poisoning again, unless she went back to heroin.

through the very end of her taper and possible withdrawal symptoms — not even 15 or 20 tabs. Valium is very addictive, you know. But that was okay: they’d taper together. She’d come to the office every week — not an easy trek for a mother of three small kids, but it was important for him to see her, to monitor her. And she would reduce her intake by one tablet — 30 mg — at a time, he insisted. But she had to agree that every time she reduced her dose, she’d have to maintain the new level. She couldn’t go back up. Not even for a particularly bad day. He knew what was best for her. Did she agree? Did she have a choice? If she didn’t agree he’d stop her prescription, and then she’d be in danger of paracetamol poisoning again, unless she went back to heroin. I saw Sally next a few days after that visit. Her energy was gone. Her smile was sad and cynical. She’d gone back up to her previous high dose, including the paracetamol torpedoes, because…because it wasn’t her recovery anymore. That’s how she put it. And it was none of his damn business and she didn’t like his rules and she didn’t like him. But the threat of a sudden withdrawal trumped all that. That was the power he wielded, and he knew it.

I saw Sally next a few days after that visit. Her energy was gone. Her smile was sad and cynical. She’d gone back up to her previous high dose, including the paracetamol torpedoes, because…because it wasn’t her recovery anymore. That’s how she put it. And it was none of his damn business and she didn’t like his rules and she didn’t like him. But the threat of a sudden withdrawal trumped all that. That was the power he wielded, and he knew it.

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica.

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica. The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain.

The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain. defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning!

defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning! at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

The bottom-line is that

The bottom-line is that  opioid overdose. The

opioid overdose. The  However, with the rise in availability of opioid-derived prescription pills, more young adults were switching to these painkillers, which have a high potential for overdose when mixed with other drugs. A subset of these users would go on to heroin, especially when prescription regulations reduced the availability of legal drugs. As most readers know, the extremely high overdose rates of the last few years have been driven primarily by fentanyl-laced (or -replaced) heroin. Unlike

However, with the rise in availability of opioid-derived prescription pills, more young adults were switching to these painkillers, which have a high potential for overdose when mixed with other drugs. A subset of these users would go on to heroin, especially when prescription regulations reduced the availability of legal drugs. As most readers know, the extremely high overdose rates of the last few years have been driven primarily by fentanyl-laced (or -replaced) heroin. Unlike  in the past, when young adults using drugs or alcohol mostly survived to go on and live normal lives (probably like most of those reading this blog), these kids were dying instead.

in the past, when young adults using drugs or alcohol mostly survived to go on and live normal lives (probably like most of those reading this blog), these kids were dying instead. I am on the board of

I am on the board of  Americans have a long history of deterministic thinking when it comes to human behavior. Starting with Calvinistic predeterminism in colonial America and then evolving into Eugenics, the American view of genetic influences rarely goes beyond a limited and simplistic notion of Mendel’s pea experiments (perhaps a topic for a future blog post).

Americans have a long history of deterministic thinking when it comes to human behavior. Starting with Calvinistic predeterminism in colonial America and then evolving into Eugenics, the American view of genetic influences rarely goes beyond a limited and simplistic notion of Mendel’s pea experiments (perhaps a topic for a future blog post). neurochemicals in the brain. What most Americans have not yet grasped is that MAT, or any other substance that alters the brain’s neurochemicals, simply combats symptoms, which is not so different from how cold medicines alleviate symptoms rather than cure the actual cold. The key difference here is that OUD symptoms induce so much suffering that users are often driven to continue using. Opioids are of course the best (if not only) way to control opioid withdrawal symptoms. In this respect, relieving symptoms, though not a cure, can change behavior patterns that exacerbate the underlying problem.

neurochemicals in the brain. What most Americans have not yet grasped is that MAT, or any other substance that alters the brain’s neurochemicals, simply combats symptoms, which is not so different from how cold medicines alleviate symptoms rather than cure the actual cold. The key difference here is that OUD symptoms induce so much suffering that users are often driven to continue using. Opioids are of course the best (if not only) way to control opioid withdrawal symptoms. In this respect, relieving symptoms, though not a cure, can change behavior patterns that exacerbate the underlying problem.