Hi all,

This morning I finally had a chance to listen to our debate in Amsterdam from 9th January. And I find that we are not that far apart on some points, though we remain in opposite corners on others. When I posted the slides from my talk and described the evening’s dialogue, my impression was that I was taking on the disease model as a sort of David fighting Goliath (a handy form of grandiosity when you’re the weakling). And while we did and do clash swords at times, maybe that’s only half the story.

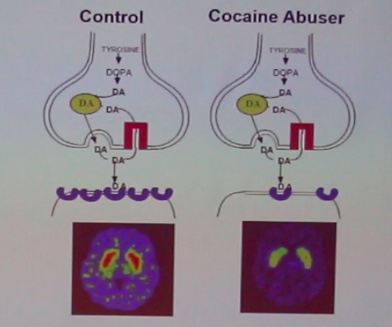

One of Nora Volkow’s slides

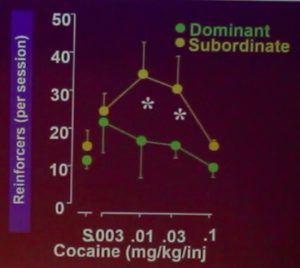

What does it signify that Nora Volkow talked explicitly about the power of the social environment, the role of stress in triggering relapse, the risk created by growing up poor, with inadequate parental monitoring? What about her emphasis on the value of positive social relationships and support? Her clear (and to my ears novel) discussion of recovery, of the fact that many one-time addicts get over it — for good — which seems a far cry from NIDA’s characterization of addiction as a chronic disease? In fact Nora showed a slide depicting how social subordination (at least in monkeys)  greatly increases vulnerability to addiction — and the brain mechanics that might underlie this relationship. It was a slide I might have used myself, as it identifies addiction as a response to low self-esteem, isolation, and/or frustration — a point that Carl Hart or Johann Hari or I might just as easily have made.

greatly increases vulnerability to addiction — and the brain mechanics that might underlie this relationship. It was a slide I might have used myself, as it identifies addiction as a response to low self-esteem, isolation, and/or frustration — a point that Carl Hart or Johann Hari or I might just as easily have made.

What I think it shows is that Nora Volkow is talking about addiction in a broader light than ever before, paying homage to the social, psychological, and even societal forces that get people to take drugs. And maybe it shows that Nora Volkow can lead NIDA and similar organizations into a more evolved understanding of addiction, rather than serve as an anchor that holds the disease model in place. In fact — and this is purely speculation — maybe Nora finds herself between a rock and a hard place, trying to balance the pathology-oriented brain data (and the research program that spawns it) against insights that are sensitive, humanistic, and true to the actual experience and context of addiction in our society. And/or maybe Stanton Peele, Bruce Alexander, Maia Szalavitz, Carl Hart and others (like me) have been nipping at her heels to some effect.

She and I still have our differences of course. I can’t stand her slides showing big red or yellow splotches on the brain scans comparing cocaine addicts to “normals”. She and her colleagues certainly know that cocaine and other psychostimulants compile dopamine in the synapses, unlike the many other addictive drugs that do no such thing, which could easily explain a temporary blunting of dopamine metabolism as a compensation. Yet she points to those slides and says: see, look how different their brains are. Not fair! And she still talks about addiction as destroying will power, which still seems to me entirely wrong-headed (though that’s sometimes how it seems). And then I wonder, is that her talking, or is that the NIDA party line? And if it’s the latter, then maybe she really is walking a kind of professional tightrope or perhaps struggling with her own intuitions while trying to be a good scientist. I know that feeling myself.

She and I still have our differences of course. I can’t stand her slides showing big red or yellow splotches on the brain scans comparing cocaine addicts to “normals”. She and her colleagues certainly know that cocaine and other psychostimulants compile dopamine in the synapses, unlike the many other addictive drugs that do no such thing, which could easily explain a temporary blunting of dopamine metabolism as a compensation. Yet she points to those slides and says: see, look how different their brains are. Not fair! And she still talks about addiction as destroying will power, which still seems to me entirely wrong-headed (though that’s sometimes how it seems). And then I wonder, is that her talking, or is that the NIDA party line? And if it’s the latter, then maybe she really is walking a kind of professional tightrope or perhaps struggling with her own intuitions while trying to be a good scientist. I know that feeling myself.

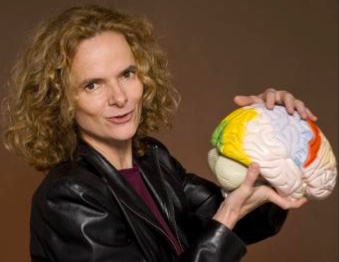

I quite like this woman. Her very expressive face (sometimes pleasant, sometimes fierce) is currently looking up at me from the cover of LEF magazine, a Dutch publication for addicts and those who live or work with them. I admire her energy and her devotion to data, not to mention the heap of accomplishments she’s contributed as an active neuroscientist — regardless of or despite her role as the head of NIDA. So I’ll end with a paragraph from an email I just sent her.

I quite like this woman. Her very expressive face (sometimes pleasant, sometimes fierce) is currently looking up at me from the cover of LEF magazine, a Dutch publication for addicts and those who live or work with them. I admire her energy and her devotion to data, not to mention the heap of accomplishments she’s contributed as an active neuroscientist — regardless of or despite her role as the head of NIDA. So I’ll end with a paragraph from an email I just sent her.

Hi Nora,

I finally had a chance to listen to the recording made that evening in Amsterdam. I want to say that I have now really listened to your words, and I see that our perspectives are getting more and more convergent. Your emphasis on environmental factors, on the importance of social support in recovery, your discussion of diversity in outcomes…so many things we actually agree on. And of course we also agree (and I acknowledged) how important it is to stop blaming and start helping. I feel a bit guilty, partly because you were so tired that night — I thought it was heroic that you spoke so energetically and clearly after three days of meetings and talks..and jet lag — but also because my main points were critical of the traditional disease model, and maybe I didn’t acknowledge how much your thinking seems to be increasingly comprehensive, and how much common ground we can find.

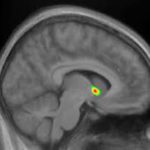

spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events.

spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events. I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped.

I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped. That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a

That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a  phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

Companies with ties to multiple other entities and those that have major influence on the healthcare economy are able to skirt the rules and make deals with federal agencies or court systems to avoid serious legal repercussions. Pfizer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, marketed a drug called Bextra in 2001, a Cox-2 inhibitor. While the FDA rejected the drug at high doses for acute surgical pain, Pfizer and its marketing partner Pharmacia pitched it to anesthesiologists and surgeons anyway — at doses up to

Companies with ties to multiple other entities and those that have major influence on the healthcare economy are able to skirt the rules and make deals with federal agencies or court systems to avoid serious legal repercussions. Pfizer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, marketed a drug called Bextra in 2001, a Cox-2 inhibitor. While the FDA rejected the drug at high doses for acute surgical pain, Pfizer and its marketing partner Pharmacia pitched it to anesthesiologists and surgeons anyway — at doses up to  breakthrough in pain management. The active ingredient of OxyContin is oxycodone, a long-lasting narcotic with

breakthrough in pain management. The active ingredient of OxyContin is oxycodone, a long-lasting narcotic with  In order to shift this perception, Purdue Pharma launched a

In order to shift this perception, Purdue Pharma launched a  In an effort to maximize the efficacy of their marketing efforts, Purdue

In an effort to maximize the efficacy of their marketing efforts, Purdue  2001) led to a tremendous increase in the number of visits to physicians with higher than average rates of opioid prescription. While pitching OxyContin, sales representatives for Purdue even reportedly claimed to some healthcare providers that the drug, now frequently compared to heroin in terms of potency and risk of addiction,

2001) led to a tremendous increase in the number of visits to physicians with higher than average rates of opioid prescription. While pitching OxyContin, sales representatives for Purdue even reportedly claimed to some healthcare providers that the drug, now frequently compared to heroin in terms of potency and risk of addiction,  ineffective. Patients can help by never sharing or selling prescription pain medications, and by taking steps to ensure that they are the only ones with access to their painkillers. Friends and loved ones can help by monitoring patients for correct usage of prescription pain medications, staying alert for any signs of prescription drug overuse, and questioning and challenging potentially dangerous habits before they become entrenched. The battle can be won, but we all must fight together.

ineffective. Patients can help by never sharing or selling prescription pain medications, and by taking steps to ensure that they are the only ones with access to their painkillers. Friends and loved ones can help by monitoring patients for correct usage of prescription pain medications, staying alert for any signs of prescription drug overuse, and questioning and challenging potentially dangerous habits before they become entrenched. The battle can be won, but we all must fight together.

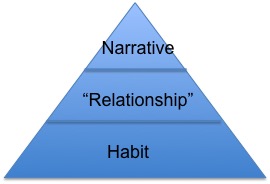

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one:

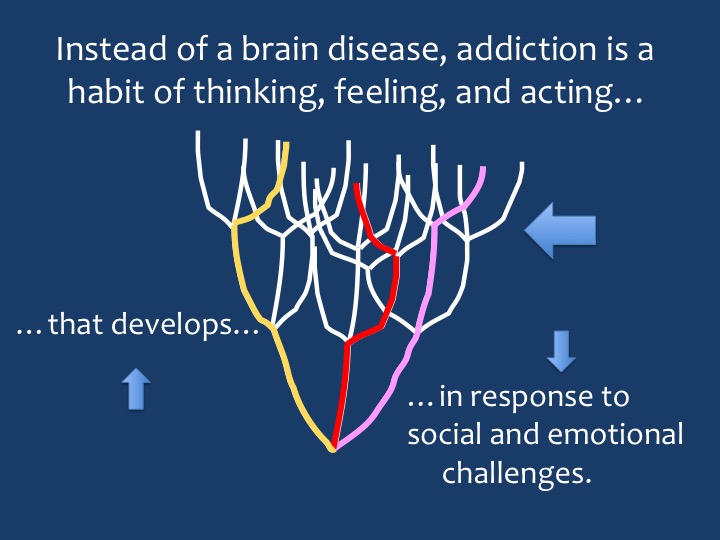

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one: The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and

The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and  conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained.

conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained. secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need.

secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need. Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

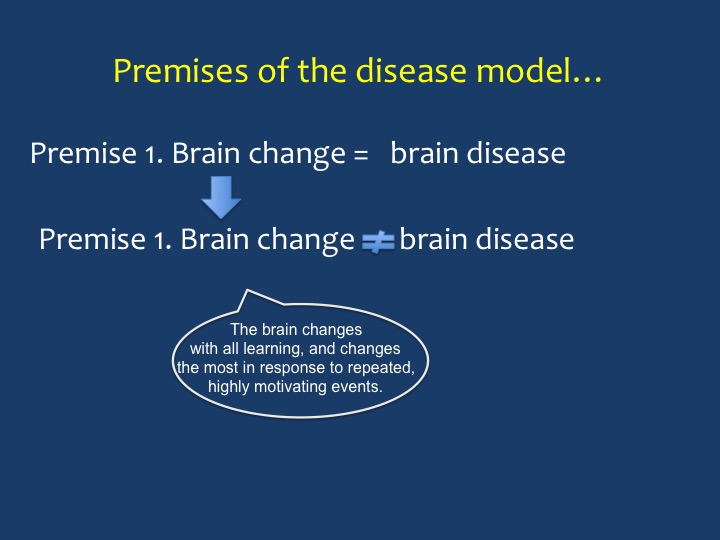

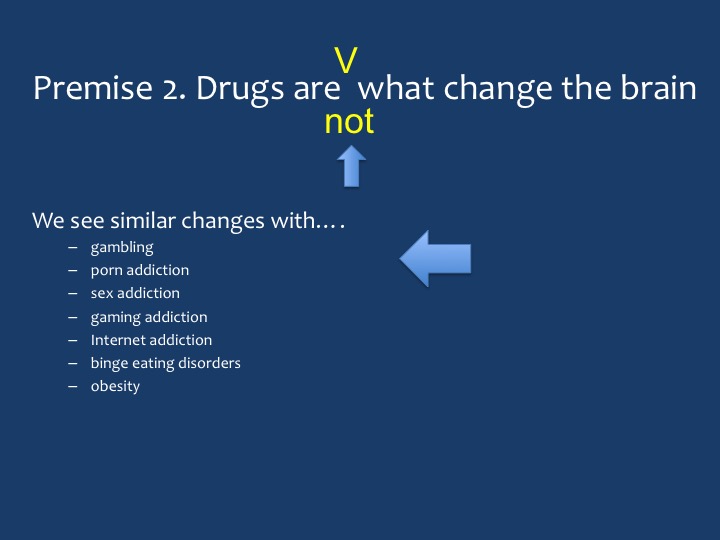

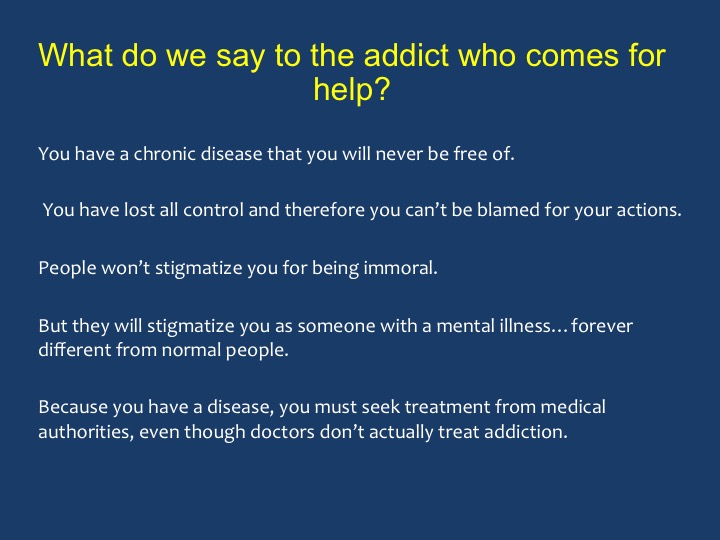

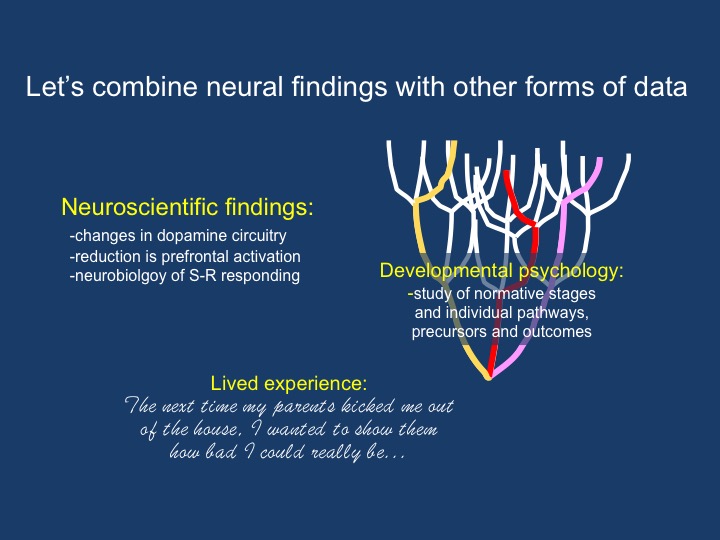

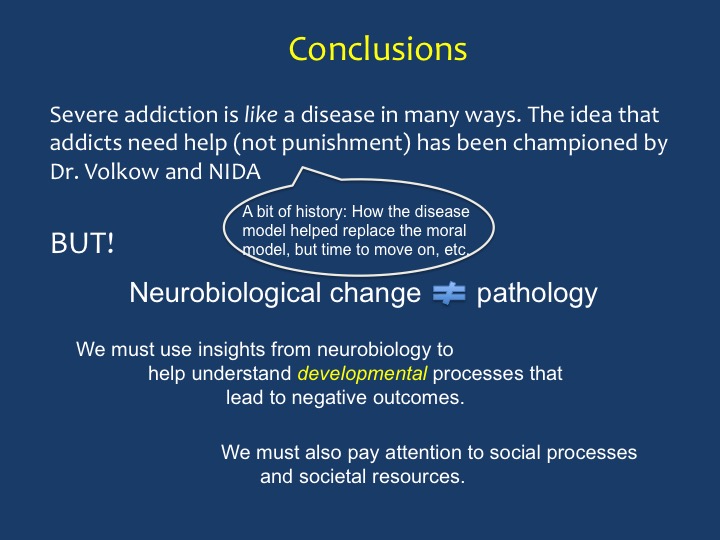

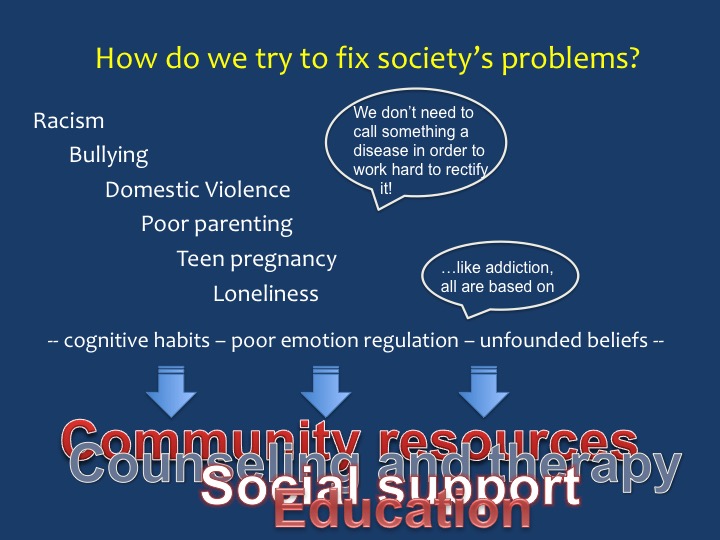

It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below.

It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below. It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay.

It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay. So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.

So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.