Just got back from the US the day before yesterday, and I’m mostly trying to reset my body clock, nine hours ahead of where it was in California, or maybe behind, or is it ten hours with Daylight Savings…? I haven’t quite got it worked out.

Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube. Here it is. Thanks to Shaun Shelly for crunching all those gigs into something relatively bite-sized (pun intended?) and doing whatever he had to do to dampen background noise. The sound quality isn’t bad for a talk in a theatre.

Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube. Here it is. Thanks to Shaun Shelly for crunching all those gigs into something relatively bite-sized (pun intended?) and doing whatever he had to do to dampen background noise. The sound quality isn’t bad for a talk in a theatre.

I’ve got lots more to share with you from my time in the US. I continue to love Americans, loathe their politics, and try to stay afloat in that peculiarly American miasma made of equal parts hope and despair. The societal challenges are so huge. How will they ever be resolved?

But the biggest challenge I witnessed, up close, in my face, was the suffering and anxiety, the attempts to come to grips with mortality rates and the loss of friends and loved ones, that continue characterize the opioid epidemic. Overdose deaths are still the leading cause of death in Americans under 50. And suicide is a close second (in some reports), exacerbated not only by substance use but prevalent during periods of abstinence. The system (if we can even call it that) is completely broken.

I gave a talk in Long Island and did some version of my usual spiel about the “disease” label and the problems it creates, in our scientific and social understanding of addiction and in the twisted ethos of a treatment industry powered by profit and offering little more than a quick fix for a problem with deep roots. But the day after my talk, something changed. I sat on a panel with the program directors of several community and state organizations tasked with helping addicts survive and, ideally, stop using. The meeting and discussion were hosted by THRIVE, a community-based organization (note: this is not the for-profit rehab by the same name) that describes itself this way:

Why THRIVE is DifferentLaunched in response to our community need for a safe, substance-free place, THRIVE is the first and only of its kind on Long Island. Members of the recovery community and their families can pursue better skills, better relationships, and ultimately better lives.

But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

So this is what I learned from the mind-boggling accounts of the obstacles people STILL face getting methadone or Suboxone (without long waits, trails of paper work, or intolerable commutes) or half an hour

So this is what I learned from the mind-boggling accounts of the obstacles people STILL face getting methadone or Suboxone (without long waits, trails of paper work, or intolerable commutes) or half an hour  with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it.

with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it.

I’ll end with a historical note that shows where we’ve come from (in drug treatment policy), where we’ve arrived, and how little has changed in the meantime. (This comes from Mike Ashton’s marvelous site with its collection of facts and figures related to drugs, alcohol, and addiction in general.)

I’ll end with a historical note that shows where we’ve come from (in drug treatment policy), where we’ve arrived, and how little has changed in the meantime. (This comes from Mike Ashton’s marvelous site with its collection of facts and figures related to drugs, alcohol, and addiction in general.)

Writing in 2010, years after his tenure at NIDA had ended, Dr Leshner revealed that his depiction and promotion of the [brain disease] model owed much to its public relations utility. He had appreciated its “powerful potential to change the way the public sees addiction”, and sought a resonant metaphor to realise that potential. The solution was to liken changes in brain structure and functioning caused by repeated drug use to a ‘switch’, transforming what was voluntary into compulsively involuntary drugtaking – a metaphor which he admitted was chosen without too much regard to the reality of neural functioning.

In other words, calling addiction a brain disease never meant much of anything to begin with, except as a prod for public health awareness and access.

So if that’s what we have to call it to get people what they need, in a country whose healthcare system is almost entirely lacking in rationality or compassion, then that’s just the way it is.

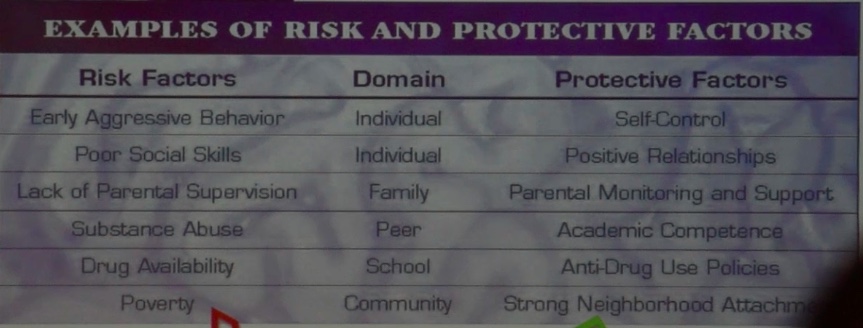

greatly increases vulnerability to addiction — and the brain mechanics that might underlie this relationship. It was a slide I might have used myself, as it identifies addiction as a response to low self-esteem, isolation, and/or frustration — a point that

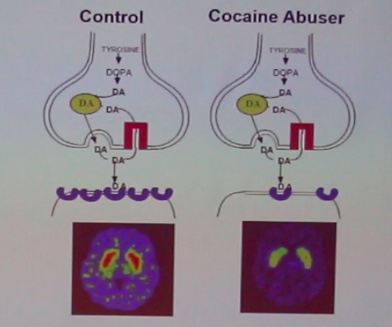

greatly increases vulnerability to addiction — and the brain mechanics that might underlie this relationship. It was a slide I might have used myself, as it identifies addiction as a response to low self-esteem, isolation, and/or frustration — a point that  She and I still have our differences of course. I can’t stand her slides showing big red or yellow splotches on the brain scans comparing cocaine addicts to “normals”. She and her colleagues certainly know that

She and I still have our differences of course. I can’t stand her slides showing big red or yellow splotches on the brain scans comparing cocaine addicts to “normals”. She and her colleagues certainly know that  I quite like this woman. Her very expressive face (sometimes pleasant, sometimes fierce) is currently looking up at me from the cover of

I quite like this woman. Her very expressive face (sometimes pleasant, sometimes fierce) is currently looking up at me from the cover of

spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events.

spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events. I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped.

I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped. That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a

That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a  phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

Companies with ties to multiple other entities and those that have major influence on the healthcare economy are able to skirt the rules and make deals with federal agencies or court systems to avoid serious legal repercussions. Pfizer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, marketed a drug called Bextra in 2001, a Cox-2 inhibitor. While the FDA rejected the drug at high doses for acute surgical pain, Pfizer and its marketing partner Pharmacia pitched it to anesthesiologists and surgeons anyway — at doses up to

Companies with ties to multiple other entities and those that have major influence on the healthcare economy are able to skirt the rules and make deals with federal agencies or court systems to avoid serious legal repercussions. Pfizer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, marketed a drug called Bextra in 2001, a Cox-2 inhibitor. While the FDA rejected the drug at high doses for acute surgical pain, Pfizer and its marketing partner Pharmacia pitched it to anesthesiologists and surgeons anyway — at doses up to  breakthrough in pain management. The active ingredient of OxyContin is oxycodone, a long-lasting narcotic with

breakthrough in pain management. The active ingredient of OxyContin is oxycodone, a long-lasting narcotic with  In order to shift this perception, Purdue Pharma launched a

In order to shift this perception, Purdue Pharma launched a  In an effort to maximize the efficacy of their marketing efforts, Purdue

In an effort to maximize the efficacy of their marketing efforts, Purdue  2001) led to a tremendous increase in the number of visits to physicians with higher than average rates of opioid prescription. While pitching OxyContin, sales representatives for Purdue even reportedly claimed to some healthcare providers that the drug, now frequently compared to heroin in terms of potency and risk of addiction,

2001) led to a tremendous increase in the number of visits to physicians with higher than average rates of opioid prescription. While pitching OxyContin, sales representatives for Purdue even reportedly claimed to some healthcare providers that the drug, now frequently compared to heroin in terms of potency and risk of addiction,  ineffective. Patients can help by never sharing or selling prescription pain medications, and by taking steps to ensure that they are the only ones with access to their painkillers. Friends and loved ones can help by monitoring patients for correct usage of prescription pain medications, staying alert for any signs of prescription drug overuse, and questioning and challenging potentially dangerous habits before they become entrenched. The battle can be won, but we all must fight together.

ineffective. Patients can help by never sharing or selling prescription pain medications, and by taking steps to ensure that they are the only ones with access to their painkillers. Friends and loved ones can help by monitoring patients for correct usage of prescription pain medications, staying alert for any signs of prescription drug overuse, and questioning and challenging potentially dangerous habits before they become entrenched. The battle can be won, but we all must fight together.

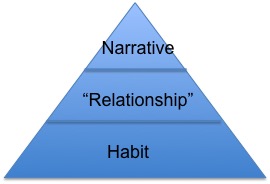

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one:

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one: The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and

The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and  conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained.

conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained. secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need.

secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need. Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.