Expediting abstinence: Drugs that can help replace addictive habits

…by Colin Brewer…

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow.

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow.

………………………………

Having plenty of spare time on Covid lockdown, can I float a couple of evidence-based ideas to this experienced readership? (My own experience is only as a physician who treated assorted addicts. Unlike many US addiction medics, most European ones are not ‘in recovery’.)

1. Though not all substance abuse represents the drowning of internal and external sorrows, quite a lot does. However, the main difference between those who drown them and those who don’t is not that the former have bigger sorrows to drown; it’s that they have got into the habit of drowning them while the others have not. Addiction is therefore to a large extent a matter of habit and habits can be unlearned as well as learned. One of our main habits is speaking only one language. To learn another language requires the unlearning of that habit for long enough to allow another linguistic habit to get established. Research — lots of it — consistently shows that the best and quickest way to learn a new language and become fluent is to be forced to speak the new language exclusively from Day 1 for hours at a time, however badly. Language schools charge big fees for creating an environment where this happens and students routinely achieve at least basic fluency within a week. You can do the same by living on your own in a village where nobody speaks English. Necessity is a great teacher.

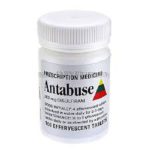

2. In the case of drug addiction (including alcohol of course) the evidence strongly indicates — as does common sense — that people who have not responded well to previous treatment and have had several relapses with no more than a few weeks or months of abstinence, need at least 18 months of  abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction.

abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction.

The German OLITA study — probably the most important (and encouraging) alcoholism treatment study bar none — showed that once a group of very unpromising alcoholics with numerous treatment failures had taken disulfiram  under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,

under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,  most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year

most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year  in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

A recent New Zealand study showed how disulfiram effectively removes one of the most annoying features of being an alcoholic — the endless internal arguments and conversations that patients have with themselves almost every minute of the day about whether they should or shouldn’t drink. Some patients described it as a sort of “internal homunculus that demanded alcohol.” Disulfiram replaced those endless ruminations and temptations with a mind-set in which alcohol was “simply no longer an option.” One patient described how, when he wasn’t taking disulfiram, after all the internal arguments, “at the end of it, I just go ‘fuck it, fuck it’… When I’m on Antabuse, it’s just like. Well, I can’t.” After a year or even less, that ‘Well, I can’t’ increasingly morphs into ‘Well, it doesn’t seem that important now. I’m learning to manage without it and I’ve found other things to do instead.’

Some people who have learned to become indifferent to alcohol can even progress to cautious experiments with controlled drinking, though if it gets uncontrolled, they should get the message and not try again. And I doubt whether trying controlled opiate use is ever a good idea. However, there are undoubtedly people whose brains do not adapt to long-term opiate abstinence and who are better off on long-term methadone, buprenorphine or — in Britain at least — morphine.

I’d really appreciate the views of people for whom those internal arguments are a daily experience — or were until recently; or who have left them behind. I am fortunate only to have encountered them at second hand.

…………..

Brewer C, Streel E. Antabuse treatment for alcoholism. An evidence-based handbook for medical and non-medical clinicians. Foreword by William R Miller. CreateSpace IPP. North Charleston, SC. 2018

But the most interesting event of my trip was meeting a man named Colin Brewer. If you google him you’ll see that he’s a wild child in British psychiatry circles. Most recently he was villainized by the media for providing

But the most interesting event of my trip was meeting a man named Colin Brewer. If you google him you’ll see that he’s a wild child in British psychiatry circles. Most recently he was villainized by the media for providing  supportive assessments

supportive assessments  We wasted no time discussing whether addiction was a disease or not. We both saw the classic disease model as a dead-end. Rather, we talked about the power of placebos, the extent to which addiction includes placebo-like effects — namely the belief that taking something has particular benefits, when the belief creates the benefits. Colin introduced me to a study showing that even physical withdrawal symptoms can follow sudden termination of a placebo believed to be an addictive drug. Fascinating!

We wasted no time discussing whether addiction was a disease or not. We both saw the classic disease model as a dead-end. Rather, we talked about the power of placebos, the extent to which addiction includes placebo-like effects — namely the belief that taking something has particular benefits, when the belief creates the benefits. Colin introduced me to a study showing that even physical withdrawal symptoms can follow sudden termination of a placebo believed to be an addictive drug. Fascinating!

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments