The coronavirus pandemic reminds us not only of the proximity of death (and other fun stuff) but of the contradictions we face throughout our lives. Some of which seem truly unsolvable. Here’s one that’s had me chasing my tail for awhile:

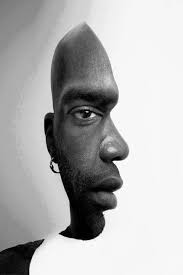

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see.

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see.

(I’ll get to the neuroscience view of the self another time. Just wanted to throw it in as a teaser for now.)

Trapped in the living room

For the last four days my family and I have been camping out at home. On Tuesday, my wife Isabel told her grad students and colleagues that she’d meet them via Skype of Zoom. She said group meetings at the university weren’t safe. They thought she was nuts. Over-reacting. How many times having have you heard that term this week? On Wednesday, she decided to keep our boys (almost-14-year-old twins) home from school, and left me to explain to the school authorities that, no, Ruben and Julian don’t appear to be sick at all. We’re just being cautious. Um, you can’t really do that, they said. The law is that children must be in school. But growth curves show no mercy. On Thursday, the university announced that large classes were cancelled, were shifting to online lectures. On Friday, the university announced that it was closing completely. And the boys’ school sent out an urgent email: keep your kids at home. No more school this week. Not much joy in saying I told you so. We figure that here in the Netherlands we’re about a week behind Italy (a close neighbour) and quickly approaching the UK scenario.

Our boys have been studying, reviewing, forging ahead with new chapters in schoolbooks whose names I no longer feel I need to know how to pronounce. They earn an hour of screen time for every two hours of studying. So…not a total loss in their view. Sometimes it’s eerily quiet in the living room, while four medium-to-large-sized mammals sit and whisper to themselves, until the sounds of clashing swords tear through the silence. No, not the long-awaited Gen-Z rebellion. Just somebody’s headphones coming off during a video game. And I watch Alexios, Julian’s ruggedly good-looking ancient Greek mercenary, try yet again to defeat Medusa and her guards. That’s father-son bonding, right? — justifiably my homework. I love it.

We Dutch (we’re actually Canadians, still searching for an identity) are known for our confidence, everything under control, we know how to deal with floods and such. And we’re super industrious and smart, highly skilled at cooperation. In fact this has evolved into an almost animal instinct to follow rules — all rules, any rules (e.g., the rule that kids must be in school unless they’re really sick, even during a pandemic).

How to torture the Dutch

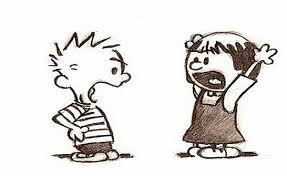

Want to know how to torture a Dutch person? (I say this with real affection, and just a bit of mockery. I’m allowed…after living here for nine years). When there is absolutely no traffic, anywhere, in any lane, as far as the eye can see, you cross the street, EVEN THOUGH THE  LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “Why Buddhism is True” and Sam Harris’s “Waking Up,” suggests that the Buddha might have been deliberately trying to get you to have a mental breakdown anyway.

LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “Why Buddhism is True” and Sam Harris’s “Waking Up,” suggests that the Buddha might have been deliberately trying to get you to have a mental breakdown anyway.

The point

Here’s another paradox, a logical polarization, that could drive you as crazy as the Dutch people on the sidewalk facing freedom directly, right now, but longing for a green light regardless.

What’s the worst that can happen, coronavirus-wise? It’s obvious: you can die. Or perhaps worse, one or more of the people you love can die. So, there’s death. And we’re all going to die anyway. So, is death really such a big deal? According to Buddhism, and as expressed so starkly by the authors I mentioned, the problem with death is that we are attached to the illusion of having a self. When you get right down to it, the self just isn’t real. The stuff going on inside you and  the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

So let’s say the Buddhists are right and there really is no self. I believe this to be true. And yet: I have advised many clients (and other people) and myself (frequently in fact) to talk to oneself (Notice that words containing “self” reappear annoyingly often.) In particular, if you’re depressed or feeling empty, or a dark, anxious state is settling over you, as is often the case AFTER (or during, or even before) a period of addiction, then one of the most helpful things you can do is talk to yourself, either out loud or in your head, in a friendly way. This corresponds to “self-compassion,” which is all over the Net these days, which I sometimes discuss on this blog, and which is one of the driving principles of “lovingkindness” meditation: you start by loving yourself, and that makes it easier to love others. Addicts are notorious for self-hatred. We’ve discussed the reasons why over many previous posts. I see it as a key goal of addiction psychotherapy to get rid of this self-hatred before it gets rid of you.

I often advise people specifically to say things like “Good morning Jo (one’s own name). Hey, how’s it going? Not so great? Don’t worry. You’re not a bad person. Even if you slipped up last night, even if the label “addict” still hangs in the air, you’re not some despicable reptile. You’re just trying to hurt less. Self-blame and self-hatred simply aren’t appropriate. You didn’t ask to have the life you’ve had, to be exposed to that kind of pain and then discover an escape route, and you’ve been doing your best to get it under control — and succeeding! When you switch to first-person and say these friendly, nurturing things to yourself, it sounds like, “I’m okay…I really am trying…I’m not bad” and then you start to feel different. Whether you pitch this conversation in terms of a you or in terms of an I, there’s an explicit assumption that there’s a self, a self that you are trying to accept, comfort, nurture, and love.

But what if the self is an illusion? Maybe something like that tortuous stoplight? How would we make sense of this paradox?

Here are three approaches:

- Tonight I had dinner with a good friend and his 15-year-old daughter, Bo. When I revealed my conceptual conundrum at dinner (Pieter is a philosopher, so this would be acceptable table talk) Bo said: If there’s no self, just a bunch of thoughts, then don’t try to be nice to your self. Just be nice to your thoughts. (Brilliant, don’t you think?)

- Saying to yourself that you really are a good self, and you shouldn’t carry around this load of self-blame and so forth, is absolutely the right thing to do. Because, first, it works: it makes you feel happier, lighter, more open, less depressed. And second, talking to your “self” this way doesn’t mean there has to be a real self in operation. The reason it works, the only reason it works, may be that it dilutes or refutes the conviction that you are a BAD self. Not even that you have a bad self; that you are a bad self. Getting rid of that just brings you back to neutral, back to zero, which seems approximately where the Buddha wanted you to end up. Not so you could just be dull and blank and detached, but because “neutral” in this sense is an open gate, or maybe, better yet, a roundabout…from where you can move in any direction.

- Here’s an extension of #2. You probably do blame your “self” for all the shit you’ve done, all the trouble you’ve gotten into, all the hurt you’ve caused others AND yourself. Not only from being an addict, but probably from well before that started, when the lesson filling the blackboard in the kitchen was that there is indeed a you, who happens to be selfish, and greedy, and envious, and probably many other not-nice characteristics, like mean and manipulative. (What kid isn’t manipulative?) That’s a lot of badness to have to face every day of your life. Certainly no advantage when you’re trying to stop drinking or snorting stuff. And wouldn’t it be something if this flawed and fantasized vessel, the self, just happened to be the most effective means for packing guilt and shame — hence anxiety and depression — into your sense of being alive. So, being nice to yourself, being friendly to yourself, might already be accomplishing something fabulous, even if the self was always just an illusion: using one side of the illusion to dispel the other.

So, talking to your “self” in a friendly and comforting way simply diminishes the enormous weight you carry around, consisting of the sense of having a very big, very central self, who’s defining characteristics are really quite unpleasant, even ugly and revolting. In other words, maybe, if the metaphor works, when there are no cars coming, when you’re really not in any danger, then don’t worry whether the light is red, or green, or even real. That’s no longer the issue.

And here’s a little secret that I think fits just about perfectly with the thrust of ACT, which was the topic of last week’s post. If the light remains red for a very long stretch of time, and there really are no cars coming or going, then the light is probably broken. That could be an ideal time to see if you can approach things in a completely different way.

to a preordained plan, of course. It looks like this. At least it does in the Netherlands, where we go Mondag, Diensdag, Woensdag, and so forth.

to a preordained plan, of course. It looks like this. At least it does in the Netherlands, where we go Mondag, Diensdag, Woensdag, and so forth. going to feel when you think about what a shitty, selfish thing that was to say. In general, present wants, needs, urges thoroughly trump wants and needs that can’t be cashed in till later. But the kicker is that we think we’re in the driver’s seat. We think our present actions are actually generated by the conscious intentions that preceded them. Psychological and neuroscientific research is pretty clear: they’re not. They’re mostly generated by habit, context (including cues), and biased thinking. So we keep up this mythology about deliberate intentions while coming in for a landing based on factors beyond our control. This common human dilemma is nowhere as clearly demonstrated as in addiction.

going to feel when you think about what a shitty, selfish thing that was to say. In general, present wants, needs, urges thoroughly trump wants and needs that can’t be cashed in till later. But the kicker is that we think we’re in the driver’s seat. We think our present actions are actually generated by the conscious intentions that preceded them. Psychological and neuroscientific research is pretty clear: they’re not. They’re mostly generated by habit, context (including cues), and biased thinking. So we keep up this mythology about deliberate intentions while coming in for a landing based on factors beyond our control. This common human dilemma is nowhere as clearly demonstrated as in addiction.  hundred million years. So that we don’t just act on impulse; we create plans in advance that will filter, constrain, and otherwise improve our behaviour so that it isn’t just driven by impulse. Long-range planning works pretty well. Short-range planning is usually a sham, a rationale, for what you’re in the process of doing anyway.

hundred million years. So that we don’t just act on impulse; we create plans in advance that will filter, constrain, and otherwise improve our behaviour so that it isn’t just driven by impulse. Long-range planning works pretty well. Short-range planning is usually a sham, a rationale, for what you’re in the process of doing anyway. particular evening. It’s already programmed. You programmed it three weeks ago when you got the invitation. And now you’re free to enjoy or at least endure the party. You have a nicely evolved cortex and you’ve learned to use it well. Keep learning.

particular evening. It’s already programmed. You programmed it three weeks ago when you got the invitation. And now you’re free to enjoy or at least endure the party. You have a nicely evolved cortex and you’ve learned to use it well. Keep learning. How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see.

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see. LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “

LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “ the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up). Think of everyday concepts like, say, arguments. We tend to think of an argument as a war, with a winner and a loser, and a certain amount of damage. The war metaphor gives the concept “argument” its meaning. It’s not a matter of listening or sharing; it’s something you either win or lose. How do we conceptualize “communication”? Often as a conduit, a tube connecting speaker and listener. If you see communication as a conduit, then your main concern is sending a message down the tube and having it

Think of everyday concepts like, say, arguments. We tend to think of an argument as a war, with a winner and a loser, and a certain amount of damage. The war metaphor gives the concept “argument” its meaning. It’s not a matter of listening or sharing; it’s something you either win or lose. How do we conceptualize “communication”? Often as a conduit, a tube connecting speaker and listener. If you see communication as a conduit, then your main concern is sending a message down the tube and having it  received at the other end. A failure in communication is seen as an obstruction or break in the tube. But if our metaphor for communication were different, say a pool of water encompassing speaker and listener, then we’d view communication failures in a completely different way. Maybe as a drought.

received at the other end. A failure in communication is seen as an obstruction or break in the tube. But if our metaphor for communication were different, say a pool of water encompassing speaker and listener, then we’d view communication failures in a completely different way. Maybe as a drought. Containers are either very full or partly full or partly empty or very empty. See the point? The only other attribute that comes to mind is “leakiness”. If you suffer from anxiety rather than depression, this may strike a chord.

Containers are either very full or partly full or partly empty or very empty. See the point? The only other attribute that comes to mind is “leakiness”. If you suffer from anxiety rather than depression, this may strike a chord. So you wake up in the morning and you feel empty. You say to yourself: shit, I feel so empty. I’d really like to feel more full. So I will take a drug or a drink to fill myself up. Maybe not right now but soon. I really dislike this sense of emptiness so I will put something

So you wake up in the morning and you feel empty. You say to yourself: shit, I feel so empty. I’d really like to feel more full. So I will take a drug or a drink to fill myself up. Maybe not right now but soon. I really dislike this sense of emptiness so I will put something  into my self to fill it up. If you’ve ever been in addiction you know exactly what I mean. Yet the reason we feel “empty” in the first place — rather than, say, uninvolved, or emotional, or out of sorts — is because of the container metaphor. Empty containers need to be filled up.

into my self to fill it up. If you’ve ever been in addiction you know exactly what I mean. Yet the reason we feel “empty” in the first place — rather than, say, uninvolved, or emotional, or out of sorts — is because of the container metaphor. Empty containers need to be filled up. touch or pat yourself (on the outside). You’ll find that you are in fact very full. Of stuff. Tissue and muscles and blood and bone, or, maybe more to the point, you are full of chemicals; neurotransmitters (including opioids!) coursing around inside your body constantly. If you are a container, you’re certainly not an empty one.

touch or pat yourself (on the outside). You’ll find that you are in fact very full. Of stuff. Tissue and muscles and blood and bone, or, maybe more to the point, you are full of chemicals; neurotransmitters (including opioids!) coursing around inside your body constantly. If you are a container, you’re certainly not an empty one. their synapses. Or the mental activity that moves through them. The self is open, yet containers are (or can be) closed. So maybe we can experience the self as something like an antenna or radar dish or…I don’t know…something very uncontainerlike.

their synapses. Or the mental activity that moves through them. The self is open, yet containers are (or can be) closed. So maybe we can experience the self as something like an antenna or radar dish or…I don’t know…something very uncontainerlike. metaphor: the container becomes something more like a wide, rich, pipeline connecting “you” to everything else — an open passage.

metaphor: the container becomes something more like a wide, rich, pipeline connecting “you” to everything else — an open passage.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments