So much harm…

A LOT of you replied to my brief ramblings on Harm Reduction. Some of you see it as almost poisonous — a kind of quicksand making it more difficult to quit using. Others see it as a valuable perspective for helping people “where they are,” without imposing conditions or restrictions. Some of you see it as an expression of kindness, others as short-sighted or even lazy, and some note that it does more good for the society at large than for addicts trying to recover. It’s good for all of us to be aware of this diversity of opinions.

I don’t think I can help provide unity, but here are a few more impressions I got from that conference.

I mentioned in one reply, last post, how struck I was by a speaker who looked like he was about to collapse right there on the podium. A slender young man who spoke in a halting voice, sometimes unable to find his words. He  talked of being a young gay man from a traditional Chinese family. He was rejected by his family and peers with such vehemence that he ended up wandering around Toronto like a stray puppy, looking for anyone he could follow home. Not surprisingly, sex was part of that equation, and, apparently not uncommonly, so was crystal meth. Clean needles and condoms were the furthest thing from his mind. Until he got sick. Now, HIV-positive and who knows what else, he stood there, quavering, clearing his throat, telling this group of strangers all about his shameful deeds. And everybody’s heart went out to him. There wasn’t one person in the room who didn’t wish they’d gotten to him first, not to put a halt to his experimentation but to help him survive it. When he told us he’d been clean for almost four years, the room erupted in waves of applause. But it didn’t seem he’d be a poster-child for HR or anything else for very much longer.

talked of being a young gay man from a traditional Chinese family. He was rejected by his family and peers with such vehemence that he ended up wandering around Toronto like a stray puppy, looking for anyone he could follow home. Not surprisingly, sex was part of that equation, and, apparently not uncommonly, so was crystal meth. Clean needles and condoms were the furthest thing from his mind. Until he got sick. Now, HIV-positive and who knows what else, he stood there, quavering, clearing his throat, telling this group of strangers all about his shameful deeds. And everybody’s heart went out to him. There wasn’t one person in the room who didn’t wish they’d gotten to him first, not to put a halt to his experimentation but to help him survive it. When he told us he’d been clean for almost four years, the room erupted in waves of applause. But it didn’t seem he’d be a poster-child for HR or anything else for very much longer.

From that moment it was clear to me that harm reduction and abstinence were not opposing goals. And I was sold. I don’t think you can fully buy into harm reduction until you stare straight into the totality of harm.

From that moment it was clear to me that harm reduction and abstinence were not opposing goals. And I was sold. I don’t think you can fully buy into harm reduction until you stare straight into the totality of harm.

Karen, a syringe program coordinator talked with me for awhile. Big heart, yes. Weird ideas? Maybe not.

“All I want to do is house them,” she said, “give them somewhere they want to go back to. You want to make it cozy for them, help them furnish it, make it their safe place.”

You’d think that might make it more comfortable for addicts to keep on using. But that wasn’t her view.

“When that happens,” she said, “their using levels out and the risk-taking all but disappears. They stop sharing any equipment, they stick to one dealer, they tend not to use in groups, and the quantity goes down: crystal meth, Dilaudid, old-style oxycontin, you name it.”

Okay, you might wonder, but don’t you try to get them to stop? Apparently it’s hard to do both at the same time.

“If clients fail to stop using something they said they’d stop using, then I never bring it up again,” Karen said. “You never shame people, because shame is the hardest emotion, in my opinion. Kindness — that’s what you give them. You thank them for coming in.”

Others felt that way too. One heavily tattooed man who looked like he could bench-press his Harley told me, in the mildest voice: “The client is the boss. I’ll plan whatever you want…and at any point you want to change it, we’ll change it. Because it’s their life, not my expectations, that matter.”

I never stopped wondering whether this was precisely the right approach. But I became convinced it was a lot better than nothing for seriously down-and-out users. If you met them with restrictions, rules, shame or disapproval, they would simply disappear. Disappearing was one thing they were particularly good at. That and destroying themselves.

I never stopped wondering whether this was precisely the right approach. But I became convinced it was a lot better than nothing for seriously down-and-out users. If you met them with restrictions, rules, shame or disapproval, they would simply disappear. Disappearing was one thing they were particularly good at. That and destroying themselves.

My talk was well received. Almost everyone there wanted to understand how addiction works, and the neurobiology was a lot of what they were missing. But policy is not my thing. And all the biology I could offer seemed a pale wand to wave at the pain that surfaced in that room.

I left feeling that harm reduction was a desperate response to a desperate situation, bound to help those who needed it most.

P.S. Check out this recent discussion forum in the New York Times. See if you can tell the good guys from the bad guys.

there is increasing opposition to court-ordered attendance at 12-step groups, and the glaring discrepancy between the brain disease model and 12-step methods continues to…well, glare. At the interface between science and treatment, there’s new thinking about the benefits of psychedelics, new research on how meditation changes the brain, investigation of smartphone apps that might help control urges, and increasing precision in the debate between the disease model and the learning model — as both sides advance their weaponry.

there is increasing opposition to court-ordered attendance at 12-step groups, and the glaring discrepancy between the brain disease model and 12-step methods continues to…well, glare. At the interface between science and treatment, there’s new thinking about the benefits of psychedelics, new research on how meditation changes the brain, investigation of smartphone apps that might help control urges, and increasing precision in the debate between the disease model and the learning model — as both sides advance their weaponry. finding that cognition, emotion, and behaviour can’t be clearly differentiated in brain structure or function. They overlap entirely.

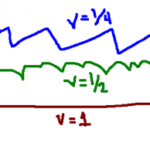

finding that cognition, emotion, and behaviour can’t be clearly differentiated in brain structure or function. They overlap entirely. To explore that question, let me tell you how scientists define a habit. And for that, we need to take a brief tour of complexity theory. According to complexity theory, a habit is a stable state in a complex system — a system composed of many interacting parts. Complex systems — such as ecosystems, societies, cultures, family dynamics, flocks of birds, herds of cattle, individual minds, individual bodies, and certainly individual brains — are made up of components (birds in a flock, family members at the

To explore that question, let me tell you how scientists define a habit. And for that, we need to take a brief tour of complexity theory. According to complexity theory, a habit is a stable state in a complex system — a system composed of many interacting parts. Complex systems — such as ecosystems, societies, cultures, family dynamics, flocks of birds, herds of cattle, individual minds, individual bodies, and certainly individual brains — are made up of components (birds in a flock, family members at the  dinner table, plants and animals in an ecosystem) that continue to influence each other. As a result, the relations between them continue to change, which means that the whole system (e.g., the family, the flock, the body, the mind) can continue to alter its form. Change is intrinsic; it doesn’t come from outside the system. Change means change in the interaction patterns, the relationship of the components, not the components themselves.

dinner table, plants and animals in an ecosystem) that continue to influence each other. As a result, the relations between them continue to change, which means that the whole system (e.g., the family, the flock, the body, the mind) can continue to alter its form. Change is intrinsic; it doesn’t come from outside the system. Change means change in the interaction patterns, the relationship of the components, not the components themselves. Your sister makes a caustic remark at the dinner table, then your mother puts down her fork, and then your father gets silent and distant, and then Aunt Jenny starts to criticize your sister. So the shape or form of the family dynamic changes, all by itself, with no particular push from the outside world.

Your sister makes a caustic remark at the dinner table, then your mother puts down her fork, and then your father gets silent and distant, and then Aunt Jenny starts to criticize your sister. So the shape or form of the family dynamic changes, all by itself, with no particular push from the outside world. them personality patterns. Personality patterns (or traits) emerge more and more predictably during childhood and adolescence. (Of course, most people have several and can even be seen switching from one to another — e.g., grumpiness to guilt — as circumstances shift.) These patterns recur, they get reinforced, they set synaptic connections into particular configurations (or recurring synaptic configurations set them, depending on how you look at it), and

them personality patterns. Personality patterns (or traits) emerge more and more predictably during childhood and adolescence. (Of course, most people have several and can even be seen switching from one to another — e.g., grumpiness to guilt — as circumstances shift.) These patterns recur, they get reinforced, they set synaptic connections into particular configurations (or recurring synaptic configurations set them, depending on how you look at it), and  they stabilize. In fact they become incredibly stable. Traits consolidate with development and they perpetuate themselves, becoming “stuck” over the lifespan.

they stabilize. In fact they become incredibly stable. Traits consolidate with development and they perpetuate themselves, becoming “stuck” over the lifespan. That’s why it’s so hard to achieve deep, lasting change through psychotherapy. Hard, but not impossible.

That’s why it’s so hard to achieve deep, lasting change through psychotherapy. Hard, but not impossible. paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, aggressive or antisocial personality style, etc, etc. All those patterns emerge and stabilize over development (even if they get a boost from genetics). They usually become stuck by early adulthood, they cause a lot of misery, and they are hard (but not impossible) to change. Addiction is just another such pattern.

paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, aggressive or antisocial personality style, etc, etc. All those patterns emerge and stabilize over development (even if they get a boost from genetics). They usually become stuck by early adulthood, they cause a lot of misery, and they are hard (but not impossible) to change. Addiction is just another such pattern. corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible.

corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible. What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,

What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,  programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits.

programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits. zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see

zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see  previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively.

previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively. If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video

If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video  games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has

games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has  Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets

Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets  of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they

of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they  also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition.

also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition. So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?

So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?

the proliferation of gun ownership in the US and the political voices that advocate it. I guess you could say it’s an emotional topic for both of us. But we differed on a sort of thought experiment: What would it be like if people could make guns on a 3D printer and those guns were entirely untraceable? Would that be a bad thing because there’d be more guns around (her point) or a good thing because the NRA and its right-wing supporters would lose their influence (my point)? The content of the argument hardly matters. Neither of us had ever thought about plastic guns before. We were speculating, and then discussing, and then debating.

the proliferation of gun ownership in the US and the political voices that advocate it. I guess you could say it’s an emotional topic for both of us. But we differed on a sort of thought experiment: What would it be like if people could make guns on a 3D printer and those guns were entirely untraceable? Would that be a bad thing because there’d be more guns around (her point) or a good thing because the NRA and its right-wing supporters would lose their influence (my point)? The content of the argument hardly matters. Neither of us had ever thought about plastic guns before. We were speculating, and then discussing, and then debating. making really good points, I told myself. I’m winning the debate. Through parry and thrust (in the language of fencing) I tried to take her down. To defeat her. All I really cared about was being right.

making really good points, I told myself. I’m winning the debate. Through parry and thrust (in the language of fencing) I tried to take her down. To defeat her. All I really cared about was being right. What I didn’t see until the next day was that Jane was hurt. She perceived my arguments as weapons — and indeed they were. I had thought: given competing positions, someone’s going to win, and that’s going to be me. She had thought: why is he putting me down? Why is he trying to cast my opinions as groundless and stupid?

What I didn’t see until the next day was that Jane was hurt. She perceived my arguments as weapons — and indeed they were. I had thought: given competing positions, someone’s going to win, and that’s going to be me. She had thought: why is he putting me down? Why is he trying to cast my opinions as groundless and stupid? going about it? Do I really want to change the minds of people steeped in medical thinking, addicts who believe they’re ill, their families, their doctors? Or do I just want to win a debate?

going about it? Do I really want to change the minds of people steeped in medical thinking, addicts who believe they’re ill, their families, their doctors? Or do I just want to win a debate? So I’m watching Matt facilitate a SMART meeting in Boston last night. SMART sometimes construes itself as “the alternative to AA.” SMART offers psychological tools, such as focusing on one’s own thought patterns and beliefs, and the potential that offers for behaviour change, even by small increments. SMART lends itself to mindfulness practices, it neither shames nor exonerates those who’ve “relapsed.” It is inclusive, it does its best to avoid dogma. And it values honesty and fellowship — as does its sometimes querulous cousin, AA.

So I’m watching Matt facilitate a SMART meeting in Boston last night. SMART sometimes construes itself as “the alternative to AA.” SMART offers psychological tools, such as focusing on one’s own thought patterns and beliefs, and the potential that offers for behaviour change, even by small increments. SMART lends itself to mindfulness practices, it neither shames nor exonerates those who’ve “relapsed.” It is inclusive, it does its best to avoid dogma. And it values honesty and fellowship — as does its sometimes querulous cousin, AA. thinking habits, to see their substance use more rationally, more comprehensively. But more than that, he was listening carefully to what people said and grasping what they were feeling: their fears, vulnerabilities, and their (often tattered) self-esteem.

thinking habits, to see their substance use more rationally, more comprehensively. But more than that, he was listening carefully to what people said and grasping what they were feeling: their fears, vulnerabilities, and their (often tattered) self-esteem. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments