A very simple reason why it’s dumb to call addiction a disease

I just listened to the first 15 minutes of a lecture by Robert Sapolsky, a renowned biologist and Stanford professor. Sapolsky begins with an incisive lesson on why humans rely on categories. Categories, he says, make it easier to think about complex phenomena. And human social behaviour is nothing if not complex. My friend Tom insisted that this online lecture series was worth viewing, and he’s right. I plan to view the rest. But first, this post.

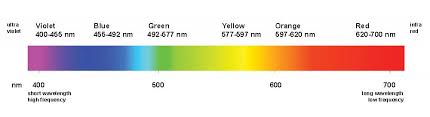

Take something a little simpler than human behaviour. If a colour falls between orange and yellow, you’ll have a harder time thinking about that colour and remembering it than if it’s either orange or yellow. Yet light frequencies fall along a continuum without boundaries. In other words, we actually invent colour boundaries, and different cultures see colour differently. It’s easier to remember a shape if you can call it a circle or a square than if it doesn’t fit any geometrical category. If the shape is squarish with rounded corners, or blob-like, you’ll have a harder time thinking about it, remembering it, and using it in a conceptual task. (Sapolsky demonstrates these examples on the white board.)

So, okay, categories are tools for simplifying perception and thought. But there are several down sides to categorical thinking. Sapolsky mentions a few, but here’s the one that inspired this post. Remember when 65 was  the cut-off between a pass and a fail? (That was the cut point when I was an undergrad.) So you’ve spent much of the week partying, getting high, etc, and here comes the exam, and you cram for it that morning, give it your best shot, and wait anxiously for the result. A

the cut-off between a pass and a fail? (That was the cut point when I was an undergrad.) So you’ve spent much of the week partying, getting high, etc, and here comes the exam, and you cram for it that morning, give it your best shot, and wait anxiously for the result. A  week later the prof hands out the exams, or you look up your grade on the bulletin board, and the thing you care about more than anything else is whether you got at least a 65. If you got a 64, you’re shit out of luck. If you got a 66, you’re sailing.

week later the prof hands out the exams, or you look up your grade on the bulletin board, and the thing you care about more than anything else is whether you got at least a 65. If you got a 64, you’re shit out of luck. If you got a 66, you’re sailing.

Now how much difference is there, really, between a 64 and a 66? How much information does that distinction actually give you, about your performance, your dedication, your intelligence, or your use of free time?

This isn’t the first time I’ve conceptualized addiction (intensity, duration, riskiness, etc) as a continuum — a continuum that does not lend itself at all to two categories, disease vs. health. Other addiction thinkers, researchers, treatment providers, etc, have also remarked that addiction  is a spectrum, a dimension, a set of gradations at best — nothing like an all-or-nothing category. Yet the disease label cannot help but classify addiction as a category. You either have tuberculosis, or diabetes, or cancer, or you don’t. Never mind that, when it comes to addiction, the category label itself can do more harm than good. As soon as you classify addiction as a disease, you draw a line. (There is some discussion of this issue in the commentaries on an article of mine.)

is a spectrum, a dimension, a set of gradations at best — nothing like an all-or-nothing category. Yet the disease label cannot help but classify addiction as a category. You either have tuberculosis, or diabetes, or cancer, or you don’t. Never mind that, when it comes to addiction, the category label itself can do more harm than good. As soon as you classify addiction as a disease, you draw a line. (There is some discussion of this issue in the commentaries on an article of mine.)

Indeed, the disease labelling trend in the US and elsewhere makes it stupidly easy to put addiction in a wastebasket category. You’ve either got it or you don’t. And if you’ve got it, then free choice, self-control, empowerment, and so many other features of human thought and emotion are neatly defined. Easier to think about, right?

Sapolsky makes other cool points about how categorical thinking obscures real complexity. For example, falling into the same category doesn’t necessarily mean that two things are similar. As we know, two people, both categorized as having the disease of addiction, can be as different as giraffes and field mice (just two animals that came to mind).

Many of my readers will probably agree that categorical thinking, this mental-labour-saving device, misses so much — so much of the real complexity of addiction — that it can’t help but muddy the waters.

………………………..

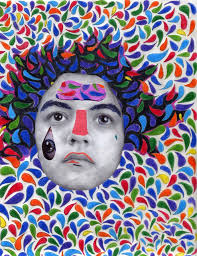

This is remarkable: four hours after posting today’s post, I found an email in my inbox that contained nothing more than this link. If this man can face his addiction and challenge it, without submitting to the disease categorization, then…that’s all there is to say. The post is electrifying, extremely well written, and deeply moving. I’m honoured that my work figures in his thinking.

What are these parts? Maybe you’ve thought of them as voices, or selves, or subpersonalities — it doesn’t matter. They appear as habitual perceptions or expectations with distinct emotional loadings (e.g., anxiety, anger, longing) — and they can be intrusive in the background or they can seem to take over.

What are these parts? Maybe you’ve thought of them as voices, or selves, or subpersonalities — it doesn’t matter. They appear as habitual perceptions or expectations with distinct emotional loadings (e.g., anxiety, anger, longing) — and they can be intrusive in the background or they can seem to take over. overtakes the system, it has no regard for tomorrow, and it’s very difficult to resist. In AA, it’s said to be doing push-ups in the parking lot. In psychology jargon, it’s called compulsion. NIDA calls it a diseased brain. But I don’t find any of these concepts at all helpful. From a neuroscience perspective, I can point to the part of the brain that “does” compulsion — the dorsolateral striatum — but all that’s really doing is putting a habit into play. And as we know, addictive urges are all about habit. So what happens if we consider this to be a part of a person that is young, energetic, one-track minded, and determined to overcome negative emotion in the only way it knows how? When you think about it that way, it’s hard to negate it or to hate it.

overtakes the system, it has no regard for tomorrow, and it’s very difficult to resist. In AA, it’s said to be doing push-ups in the parking lot. In psychology jargon, it’s called compulsion. NIDA calls it a diseased brain. But I don’t find any of these concepts at all helpful. From a neuroscience perspective, I can point to the part of the brain that “does” compulsion — the dorsolateral striatum — but all that’s really doing is putting a habit into play. And as we know, addictive urges are all about habit. So what happens if we consider this to be a part of a person that is young, energetic, one-track minded, and determined to overcome negative emotion in the only way it knows how? When you think about it that way, it’s hard to negate it or to hate it. for the last week or the last month. We often call this the internal critic, and its specialty is self-blame and self-contempt. So what happens if we see this part as a younger version of ourselves, who learned to be our caretaker or disciplinarian? You better be good! Don’t you dare goof up again! You’re going to be in real trouble if you do that!! Once we see this part as trying to help keep us out of trouble, it’s hard to feel alienated from it or even victimized by it. Instead, IFS asks us to open a dialogue with this part. For example: You come out whenever I’m likely to do something “bad” (like call my dealer), don’t you — I guess that’s been a full-time job lately. But then you get so upset with me that I get seriously depressed, and then I just want to get high all the more. Let’s try reducing the pressure a bit.

for the last week or the last month. We often call this the internal critic, and its specialty is self-blame and self-contempt. So what happens if we see this part as a younger version of ourselves, who learned to be our caretaker or disciplinarian? You better be good! Don’t you dare goof up again! You’re going to be in real trouble if you do that!! Once we see this part as trying to help keep us out of trouble, it’s hard to feel alienated from it or even victimized by it. Instead, IFS asks us to open a dialogue with this part. For example: You come out whenever I’m likely to do something “bad” (like call my dealer), don’t you — I guess that’s been a full-time job lately. But then you get so upset with me that I get seriously depressed, and then I just want to get high all the more. Let’s try reducing the pressure a bit. many times a day do you suppose the average 6-year-old thinks about NOT getting in trouble? How many times did you do bad shit anyway? The trouble now is that those two parts are so busy trying to shut each other down that you can’t get anywhere. Neither part will stop doing what it’s doing. It all seems so hopeless.

many times a day do you suppose the average 6-year-old thinks about NOT getting in trouble? How many times did you do bad shit anyway? The trouble now is that those two parts are so busy trying to shut each other down that you can’t get anywhere. Neither part will stop doing what it’s doing. It all seems so hopeless. Having practiced IFS as a therapist now for several months, I am sold on its efficiency and its power. (I’ve even begun as a client, myself, with an IFS therapist. What better way to learn the ropes…not to mention some timely self-improvement.) My clients “get it” almost at once. I don’t have to sell them on the rather esoteric imagery and jargon. They just take a look inside and say, Um yeah, that’s pretty much what’s happening. And then they start to change.

Having practiced IFS as a therapist now for several months, I am sold on its efficiency and its power. (I’ve even begun as a client, myself, with an IFS therapist. What better way to learn the ropes…not to mention some timely self-improvement.) My clients “get it” almost at once. I don’t have to sell them on the rather esoteric imagery and jargon. They just take a look inside and say, Um yeah, that’s pretty much what’s happening. And then they start to change.

stop trying so hard to unify them? Because sometimes…you just can’t. They simply don’t fit. And the effort to weld them together can be overwhelming, soul-destroying, can leave us feeling more fragmented than we already were. The

stop trying so hard to unify them? Because sometimes…you just can’t. They simply don’t fit. And the effort to weld them together can be overwhelming, soul-destroying, can leave us feeling more fragmented than we already were. The  infamous “dry drunk” is one victim of this misguided struggle.

infamous “dry drunk” is one victim of this misguided struggle. Or who I expect to become — a very different way to frame a future self!

Or who I expect to become — a very different way to frame a future self! to get high, being determined, being defiant about getting high. (Even in the world of “normies,” there are parts that don’t fit the narrative.) Maybe it’s best so see these as strands of the self-story that truly aren’t compatible with the rest. Maybe they are “clips” (when we actually bother to see them at all), but not self-stories per se. In fact, maybe their incompleteness reflects this. Maybe those strands are “doomed” to remain incomplete.

to get high, being determined, being defiant about getting high. (Even in the world of “normies,” there are parts that don’t fit the narrative.) Maybe it’s best so see these as strands of the self-story that truly aren’t compatible with the rest. Maybe they are “clips” (when we actually bother to see them at all), but not self-stories per se. In fact, maybe their incompleteness reflects this. Maybe those strands are “doomed” to remain incomplete.

per day. Sleep became sporadic and unpredictable. He could no longer think in straight lines, and fantastical whims soon replaced his customary rationality. His business fell apart, he moved in with his dealer, and his precious relationship with his young daughter turned into a parody of parenting, with him sneaking out to the car every hour or two for another hit. Meth comes on strong and brings with it clarity, optimism and brilliant energy. But Brian’s sleep loss meant that the high was increasingly short-lived. With the first hints of loss, he would grab for his pipe, eager beyond reason for another launch.

per day. Sleep became sporadic and unpredictable. He could no longer think in straight lines, and fantastical whims soon replaced his customary rationality. His business fell apart, he moved in with his dealer, and his precious relationship with his young daughter turned into a parody of parenting, with him sneaking out to the car every hour or two for another hit. Meth comes on strong and brings with it clarity, optimism and brilliant energy. But Brian’s sleep loss meant that the high was increasingly short-lived. With the first hints of loss, he would grab for his pipe, eager beyond reason for another launch. Other (interconnected) feedback loops facilitate and consolidate addiction. They include social isolation, reinforced by the addiction, which leaves the addict with fewer opportunities to reconnect with people, or with healthier pleasures. They include the rationalizations that addicts know too well: if I’m such a bad person, or so misunderstood, then I might as well do it again. Brian was a self-reflective guy; he knew how much he had lost. His ongoing self-destruction seemed a punishment for what he perceived as his failure.

Other (interconnected) feedback loops facilitate and consolidate addiction. They include social isolation, reinforced by the addiction, which leaves the addict with fewer opportunities to reconnect with people, or with healthier pleasures. They include the rationalizations that addicts know too well: if I’m such a bad person, or so misunderstood, then I might as well do it again. Brian was a self-reflective guy; he knew how much he had lost. His ongoing self-destruction seemed a punishment for what he perceived as his failure. According to classical learning theory, rewarded behaviours proliferate, while behaviours leading to adverse consequences are extinguished. Yet this clearly misses the point when it comes to the development of emotional problems. Rather, it sometimes seems that the most

According to classical learning theory, rewarded behaviours proliferate, while behaviours leading to adverse consequences are extinguished. Yet this clearly misses the point when it comes to the development of emotional problems. Rather, it sometimes seems that the most  unpleasant conditions are the most likely to become entrenched. Mental and emotional states characterized by suffering appear in adolescent development with remarkable frequency, and they continue to dominate the personality for years if not for life. Why would such negative states become attractors, become concretized and stuck?

unpleasant conditions are the most likely to become entrenched. Mental and emotional states characterized by suffering appear in adolescent development with remarkable frequency, and they continue to dominate the personality for years if not for life. Why would such negative states become attractors, become concretized and stuck? ineffective. (

ineffective. ( more fault we see; and so rejection, sadness, and shame are amplified. Anxiety draws attention to threat. That is its evolutionary purpose. Thus anxiety disorders arise from a very simple, very pernicious feedback cycle. The more anxiety, the more attention to what could go wrong, to the dangers implicit in the environment. In turn, this thinking amplifies the feeling of anxiety. And so on.

more fault we see; and so rejection, sadness, and shame are amplified. Anxiety draws attention to threat. That is its evolutionary purpose. Thus anxiety disorders arise from a very simple, very pernicious feedback cycle. The more anxiety, the more attention to what could go wrong, to the dangers implicit in the environment. In turn, this thinking amplifies the feeling of anxiety. And so on. In my book,

In my book,  psychedelic in the spirit of self-exploration; and then there’s been silly, teenage stuff for the ridiculousness of it – a whiff of amyl nitrite in the red light district of Paris, a balloon of nitrous while watching Twin Peaks. This freedom was a decision I made after two years of total abstinence, and it’s about joyous bursts, rather than the grinding self-medication of yesteryear.

psychedelic in the spirit of self-exploration; and then there’s been silly, teenage stuff for the ridiculousness of it – a whiff of amyl nitrite in the red light district of Paris, a balloon of nitrous while watching Twin Peaks. This freedom was a decision I made after two years of total abstinence, and it’s about joyous bursts, rather than the grinding self-medication of yesteryear. There will be people reading this with anger burning in their heart. To someone who is truly sober, my generous ‘you can if you want’ policy borders on betrayal. I know how that feels. I remember when a couple who had quit drinking told me that they’d each had a beer at a wedding, and reported with pleasure that they

There will be people reading this with anger burning in their heart. To someone who is truly sober, my generous ‘you can if you want’ policy borders on betrayal. I know how that feels. I remember when a couple who had quit drinking told me that they’d each had a beer at a wedding, and reported with pleasure that they  didn’t enjoy the beer and now they knew they didn’t need to wonder about it again. I felt an inexplicable fury. For me, alcohol was an absolute no-go zone; never worth risking. So that was the root of my rage: they’d made a decision that had worked out just fine for them, but it threatened my new blueprint for life.

didn’t enjoy the beer and now they knew they didn’t need to wonder about it again. I felt an inexplicable fury. For me, alcohol was an absolute no-go zone; never worth risking. So that was the root of my rage: they’d made a decision that had worked out just fine for them, but it threatened my new blueprint for life. Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, quit drinking in the thirties but experimented with LSD with Aldous Huxley in the 1950s. He even hoped LSD could prove to be beneficial to those in recovery. These days, debates rage on recovery forums as to whether opioid replacement therapy is

Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, quit drinking in the thirties but experimented with LSD with Aldous Huxley in the 1950s. He even hoped LSD could prove to be beneficial to those in recovery. These days, debates rage on recovery forums as to whether opioid replacement therapy is  okay for NA members, or whether a ‘marijuana maintenance plan’ is acceptable when attending AA. In fact it might make sense to go to an outpatient drug and alcohol service and collaborate on a plan that includes, say, moderate pot use in the service of quitting methamphetamine (this option is already available in the UK and Australia).

okay for NA members, or whether a ‘marijuana maintenance plan’ is acceptable when attending AA. In fact it might make sense to go to an outpatient drug and alcohol service and collaborate on a plan that includes, say, moderate pot use in the service of quitting methamphetamine (this option is already available in the UK and Australia). Nowhere do we dictate what a person has to do to be a part of Hello Sunday Morning. Our wording – ‘reassessing your relationship with alcohol’ – turns it into a subjective experience. Even government campaigns in Australia are starting to use that kind of wording, and that’s a good cultural shift. It’s not about ‘Are you an alcoholic? Are you addicted or not?’ It’s about ‘What relationship with alcohol would you like?’ It could be none; it could be some.

Nowhere do we dictate what a person has to do to be a part of Hello Sunday Morning. Our wording – ‘reassessing your relationship with alcohol’ – turns it into a subjective experience. Even government campaigns in Australia are starting to use that kind of wording, and that’s a good cultural shift. It’s not about ‘Are you an alcoholic? Are you addicted or not?’ It’s about ‘What relationship with alcohol would you like?’ It could be none; it could be some. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments