The future made manifest

I am finally finished the tapering period, finished getting off the oxycodone I was on pre- and post-surgery. It took about four weeks to go from 100 mg/day to zero. Nice and gradual, and I suffered nothing worse than a runny nose, some diarrhea, some insomnia, and a few twitches. Oh, and that sense of impending loss, depression, and despair. Did I mention that? The old circuits carrying that old message, because that’s what old circuits do.

So there I was, flickering into my “addict self,” as people like to call it, and thinking, I like this stuff and I’m not eager to stop…

I don’t remember who gave me this line — one of you, I’m sure: Quitting drugs is like going to the funeral of your best friend. Funny how it still feels like that. That’s what I anticipated. Not as intense as in the old days. But qualitatively pretty much the same.

I don’t remember who gave me this line — one of you, I’m sure: Quitting drugs is like going to the funeral of your best friend. Funny how it still feels like that. That’s what I anticipated. Not as intense as in the old days. But qualitatively pretty much the same.

What I wasn’t anticipating, what I’d forgotten about, was the relief I’m feeling now. An unexpected flush of freedom, breathing in lungfuls of fresh air. And feeling strong again. I feel centered, and focused, and strong. I feel like me again. It’s been awhile.

But…freedom from what? That is the big question, don’t you think? Freedom from the sense of impending loss, the sort of cowering that goes with ingesting something you imagine is enhancing your sense of okayness, knowing it’s not going to last, and putting  off the inevitable. Freedom from the compulsion, the greedy hording (mentally, at any rate) of the crumbs of wellbeing that I was still getting from these pills — even on a medically supervised, perfectly legal, moral, and even necessary detox regime. I was still getting the crumbs. And the freedom I feel now is from the anxiety — pure and simple: anxiety — about losing those crumbs.

off the inevitable. Freedom from the compulsion, the greedy hording (mentally, at any rate) of the crumbs of wellbeing that I was still getting from these pills — even on a medically supervised, perfectly legal, moral, and even necessary detox regime. I was still getting the crumbs. And the freedom I feel now is from the anxiety — pure and simple: anxiety — about losing those crumbs.

My last post addressed how it might be possible to make the future seem as good or better than the present, by adjusting the subjective value, the sense of value, of the immediate reward (drugs, booze, whatever) versus the long-term reward (that list of seeming  abstractions) and/or changing their timing. And then you guys asked, and I asked myself, how exactly do you do that? How do you do it for yourself (if you’re the addict) and how do you do it for someone else (if you’re the helper, sponsor, therapist, partner)? If we’re not in some artificial experimental setting, and it’s not just a matter of changing the numerals on a computer screen (e.g., from 10 to 45 euros in the “next week” column), how do you get the future to feel like it’s worth it?! Worth whatever you have to go through to “just say NO.”

abstractions) and/or changing their timing. And then you guys asked, and I asked myself, how exactly do you do that? How do you do it for yourself (if you’re the addict) and how do you do it for someone else (if you’re the helper, sponsor, therapist, partner)? If we’re not in some artificial experimental setting, and it’s not just a matter of changing the numerals on a computer screen (e.g., from 10 to 45 euros in the “next week” column), how do you get the future to feel like it’s worth it?! Worth whatever you have to go through to “just say NO.”

And here, ladies and gentlemen, is the answer. At least one answer.

Remind yourself or your addicted friend, lover, client or patient about this sense of relief! This feeling of being a whole person. Of being strong. Make it palpable. Get it back on the radar. Bring it to mind (hint: that’s the first half of the word “mindfulness”). This is what it feels like to finally be free of this shit! Remember? Do you get it? There is peace here.

Certainly there are twinges of wistfulness. Yes, some kind of magical sheen, winking on and off like an old neon sign, has gone missing. Craving still bunches up in your throat like a reflex, a need to swallow — or cough. But the place you land in, after these dust devils have passed…that place feels like home.

Certainly there are twinges of wistfulness. Yes, some kind of magical sheen, winking on and off like an old neon sign, has gone missing. Craving still bunches up in your throat like a reflex, a need to swallow — or cough. But the place you land in, after these dust devils have passed…that place feels like home.

Now, as to the details, how exactly to do that, I’m going to turn the floor over to someone in the treatment world. First up is my friend (through this blog) and long-time contributor (to this blog), Matt. And if anyone else would like to help us out here — anyone, but especially those of you in the treatment community — please do: get in touch about writing a guest post. Soon! I think we could all use some concrete ideas about manipulating awareness, about expanding awareness beyond the upcoming delivery of today’s lollipop, about shifting your focus…away from the siren call of the moment and back to the main voyage.

I’m off to Australia for two weeks. I’ll be doing talks, public debates, etc, on the subject of gambling as well as substance addiction. Apparently gambling is a more serious public health issue than alcohol or drug addiction in Australia. I’ll also be spending some time on a farm somewhere where they shear sheep and herd cows. Should be a nice break from urban life in Holland.

I’m off to Australia for two weeks. I’ll be doing talks, public debates, etc, on the subject of gambling as well as substance addiction. Apparently gambling is a more serious public health issue than alcohol or drug addiction in Australia. I’ll also be spending some time on a farm somewhere where they shear sheep and herd cows. Should be a nice break from urban life in Holland. hierarchies as a product of our evolution rather than the construction of an oppressive (white, male) culture. He distinguishes sex differences, which are (he claims and I certainly agree) rooted in biology and evolution, from the social construction of gender. He analyzes the personality traits associated with women and men and argues that the asymmetrical distribution of these traits (something you may have studied in Psych 101) has much to do with the gender pay gap — which is therefore not simply a result of sexism. He certainly doesn’t deny the existence of sexism, or oppression by dominant cultural forces, or the rights of transgender people. Not at all. Yet his infusion of statistically validated facts and an evolutionary perspective into the ideological battles raging (especially in the universities) about diversity, gender, social justice and so forth has alienated and angered many on the left.

hierarchies as a product of our evolution rather than the construction of an oppressive (white, male) culture. He distinguishes sex differences, which are (he claims and I certainly agree) rooted in biology and evolution, from the social construction of gender. He analyzes the personality traits associated with women and men and argues that the asymmetrical distribution of these traits (something you may have studied in Psych 101) has much to do with the gender pay gap — which is therefore not simply a result of sexism. He certainly doesn’t deny the existence of sexism, or oppression by dominant cultural forces, or the rights of transgender people. Not at all. Yet his infusion of statistically validated facts and an evolutionary perspective into the ideological battles raging (especially in the universities) about diversity, gender, social justice and so forth has alienated and angered many on the left. staunchly elevates free speech over “sensitivity” to the feelings of others. In

staunchly elevates free speech over “sensitivity” to the feelings of others. In  As a result of his stated positions, Peterson has been mobbed by what he terms “social justice warriors”– people who espouse extreme leftist views. There’s no doubt that he disagrees with many of their views and he’s angry at the insulting nature of their attacks on him. He’s literally been shouted down on more than a few campuses. Does that make him a right-winger? Not yet. The view of Peterson as a (perhaps extreme) right-winger comes from the next act in this play. People

As a result of his stated positions, Peterson has been mobbed by what he terms “social justice warriors”– people who espouse extreme leftist views. There’s no doubt that he disagrees with many of their views and he’s angry at the insulting nature of their attacks on him. He’s literally been shouted down on more than a few campuses. Does that make him a right-winger? Not yet. The view of Peterson as a (perhaps extreme) right-winger comes from the next act in this play. People  who really do identify with the right, including the far right, started to proclaim their undying loyalty to Peterson, mainly because the far left seems to hate him so much. In my view, the equation is simple. If my enemy hates you then you must be my friend. Does that make him a right-winger?

who really do identify with the right, including the far right, started to proclaim their undying loyalty to Peterson, mainly because the far left seems to hate him so much. In my view, the equation is simple. If my enemy hates you then you must be my friend. Does that make him a right-winger? too much about the fallout. I personally don’t think he enjoys being in the centre of this altercation one bit. He’s said many times in public that he’d rather people listen to, and argue with, the content of his arguments than slot him into a political ideology.

too much about the fallout. I personally don’t think he enjoys being in the centre of this altercation one bit. He’s said many times in public that he’d rather people listen to, and argue with, the content of his arguments than slot him into a political ideology. surely knows. (When Trump got elected, I wrote a post entitled “Oh Shit.” I was depressed for weeks and made no secret of it.) But that doesn’t mean I have nothing to discuss with people who see things differently. And more to the point, this blog isn’t about politics. It’s about experiential, social, psychological, and neurobiological approaches to understanding addiction. I’d be glad to chat with anyone out there about the the political eruptions surrounding Peterson’s public persona. I’m sure I can learn something. Maybe over a coffee if I’m ever in your part of the world.

surely knows. (When Trump got elected, I wrote a post entitled “Oh Shit.” I was depressed for weeks and made no secret of it.) But that doesn’t mean I have nothing to discuss with people who see things differently. And more to the point, this blog isn’t about politics. It’s about experiential, social, psychological, and neurobiological approaches to understanding addiction. I’d be glad to chat with anyone out there about the the political eruptions surrounding Peterson’s public persona. I’m sure I can learn something. Maybe over a coffee if I’m ever in your part of the world. But I think it would be a shame to ward off Peterson’s ideas as if he were some sort of vampire, simply because of the political accusations flying back and forth. I don’t agree with everything Peterson says. In my review, soon to come out, I firmly criticize him for cherry-picking scientific factoids to support dubious assumptions and for a style of argument which violates the standards of scientific discourse — namely basing one’s authority on intuitions rather than methodical arguments grounded in data. Yet some of his ideas strike me as valid, powerful, refreshing, constructive, and of particular utility for enhancing personal growth. Whether you consider yourself to be on the right or on the left, it seems there’s much of value here, and I hope you won’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

But I think it would be a shame to ward off Peterson’s ideas as if he were some sort of vampire, simply because of the political accusations flying back and forth. I don’t agree with everything Peterson says. In my review, soon to come out, I firmly criticize him for cherry-picking scientific factoids to support dubious assumptions and for a style of argument which violates the standards of scientific discourse — namely basing one’s authority on intuitions rather than methodical arguments grounded in data. Yet some of his ideas strike me as valid, powerful, refreshing, constructive, and of particular utility for enhancing personal growth. Whether you consider yourself to be on the right or on the left, it seems there’s much of value here, and I hope you won’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

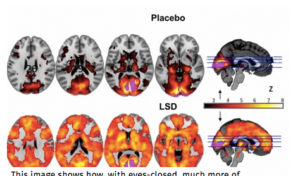

off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain

off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain  synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from

synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from  present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world.

present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world. Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté,

Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté,  in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out.

in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments