Toward an alternative approach: But first a word from our sponsor

Our sponsor is the brain, of course. So, before getting to Part 2, here’s an important message, also excerpted from the final chapter:

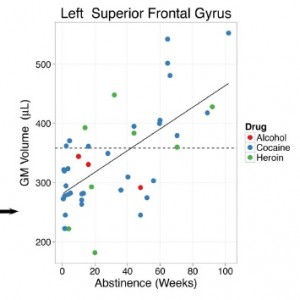

The term neuroplasticity has been bandied around a lot in recent years, but it’s been understood for at least a century. In Donald Hebb’s (1940s) memorable words: What fires together wires together — neurons that activate each other become more strongly connected — through adjustments (increased efficiency) in their synapses. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s natural starting point for any learning process. This includes the development of addiction. But is it also the springboard to recovery?

Neuroplasticity is strongly amplified when people are highly motivated. Which is why all learning requires some emotional charge, and entrenched habits like addiction grow from intense desire. Clearly, the desire to recapture a potent experience of pleasure or relief is the motivational on-ramp to addiction. But does desire also cultivate recovery?

In The Woman who Changed her Brain, Barbara Arrowsmith Young describes the many cognitive exercises she devised for herself, in order to overcome her very severe learning disabilities. She practiced these exercises prodigiously. As a result, she went from a high-school student who could not comprehend history, who even had a hard time understanding simple sentences, to a writer and teacher who has set up roughly 70 schools for learning-disabled children across North America. I met this remarkable woman in Australia, at a book fair, and I became convinced that her intuition, creativity, and determination to triumph over her learning disabilities were precisely the means by which addicts recover. I also learned her delightful phrase for the neuroplasticity needed to replace bad habits with good ones: What fires together wires together, and what fires apart wires apart. In other words, new mental patterns can fashion new and divergent synaptic avenues.

In 1993, Mogilner and colleagues looked at the brains of people plagued with webbed fingers. That means that some of their fingers were connected and could not operate separately – they functioned in total unison. After surgery was performed to allow the fingers to move on their own, these authors looked at changes in the (somatosensory) cortex. What they found was that clusters of neurons that had always fired together now fired partially independently.

In 1993, Mogilner and colleagues looked at the brains of people plagued with webbed fingers. That means that some of their fingers were connected and could not operate separately – they functioned in total unison. After surgery was performed to allow the fingers to move on their own, these authors looked at changes in the (somatosensory) cortex. What they found was that clusters of neurons that had always fired together now fired partially independently.

The presurgical maps displayed shrunken and nonsomatotopic hand representations. Within weeks following surgery, cortical reorganization occurring over distances of 3-9 mm was evident, correlating with the new functional status of their separated digits.

So the brain adjusted its wiring, breaking down the coherent habit it had assumed, based on the details of repeated action patterns, and replacing it with new habits, based on novel action patterns. In fact these changes were observable just weeks after the change in action patterns took place! Might recovery work the same way?

Just in case you think the webbed-finger analogy is far fetched, you should know that it’s not an analogy. That’s exactly how neuroplasticity works, whether dealing with severe learning problems (which no doubt involve the prefrontal cortex) or reversing a physical anomaly that took hold during prenatal development (involving the sensorimotor cortex).

When people recover from strokes or concussions, the same sort of rewiring takes place in many regions of the cortex. Even language, one of the most basic human functions, can be relearned after it has been demolished by brain damage, through the synaptic rewiring of cortical regions that previously took care of other business. Thus, neuroplastic change can and does occur, in real life, with a speed and vigor we rarely imagine.

When people recover from strokes or concussions, the same sort of rewiring takes place in many regions of the cortex. Even language, one of the most basic human functions, can be relearned after it has been demolished by brain damage, through the synaptic rewiring of cortical regions that previously took care of other business. Thus, neuroplastic change can and does occur, in real life, with a speed and vigor we rarely imagine.

Back to addiction. People learn addiction through neuroplasticity, which is how they learn everything. They maintain their addiction because they lose some of that plasticity. As if their fingers had become attached together, they can no longer separate their desire for wellbeing from their desire for drugs, booze, or whatever they rely on. Then, when they recover, whether in AA, NA, SMART Recovery, or standing naked on the 33rd-floor balcony of the Chicago Sheraton in February, their neuroplasticity returns. Their brains start changing again—perhaps radically. Just as in Mogilner’s study, their brains begin to grow new synaptic patterns to allow for those distinctions, to hold onto them over time, and thereby acquire new vistas of personal freedom and extended wellbeing.

The take-home message here is simple: Recovery involves a major change in thought and behavior, and such changes require ongoing neural development. Without developmental adjustments in synaptic patterns, we would stay exactly the way we are. Which raises the question: If the high-beam of desire is what drives the synaptic shaping of addiction, is it also the necessary ingredient for finding the road out?

The bottom-line is that

The bottom-line is that  opioid overdose. The

opioid overdose. The  However, with the rise in availability of opioid-derived prescription pills, more young adults were switching to these painkillers, which have a high potential for overdose when mixed with other drugs. A subset of these users would go on to heroin, especially when prescription regulations reduced the availability of legal drugs. As most readers know, the extremely high overdose rates of the last few years have been driven primarily by fentanyl-laced (or -replaced) heroin. Unlike

However, with the rise in availability of opioid-derived prescription pills, more young adults were switching to these painkillers, which have a high potential for overdose when mixed with other drugs. A subset of these users would go on to heroin, especially when prescription regulations reduced the availability of legal drugs. As most readers know, the extremely high overdose rates of the last few years have been driven primarily by fentanyl-laced (or -replaced) heroin. Unlike  in the past, when young adults using drugs or alcohol mostly survived to go on and live normal lives (probably like most of those reading this blog), these kids were dying instead.

in the past, when young adults using drugs or alcohol mostly survived to go on and live normal lives (probably like most of those reading this blog), these kids were dying instead. I am on the board of

I am on the board of  Americans have a long history of deterministic thinking when it comes to human behavior. Starting with Calvinistic predeterminism in colonial America and then evolving into Eugenics, the American view of genetic influences rarely goes beyond a limited and simplistic notion of Mendel’s pea experiments (perhaps a topic for a future blog post).

Americans have a long history of deterministic thinking when it comes to human behavior. Starting with Calvinistic predeterminism in colonial America and then evolving into Eugenics, the American view of genetic influences rarely goes beyond a limited and simplistic notion of Mendel’s pea experiments (perhaps a topic for a future blog post). neurochemicals in the brain. What most Americans have not yet grasped is that MAT, or any other substance that alters the brain’s neurochemicals, simply combats symptoms, which is not so different from how cold medicines alleviate symptoms rather than cure the actual cold. The key difference here is that OUD symptoms induce so much suffering that users are often driven to continue using. Opioids are of course the best (if not only) way to control opioid withdrawal symptoms. In this respect, relieving symptoms, though not a cure, can change behavior patterns that exacerbate the underlying problem.

neurochemicals in the brain. What most Americans have not yet grasped is that MAT, or any other substance that alters the brain’s neurochemicals, simply combats symptoms, which is not so different from how cold medicines alleviate symptoms rather than cure the actual cold. The key difference here is that OUD symptoms induce so much suffering that users are often driven to continue using. Opioids are of course the best (if not only) way to control opioid withdrawal symptoms. In this respect, relieving symptoms, though not a cure, can change behavior patterns that exacerbate the underlying problem. My drug use began with psychedelics. Then came heroin. They’ve always seemed like diametrical opposites. This is where I get my intuitive feel for

My drug use began with psychedelics. Then came heroin. They’ve always seemed like diametrical opposites. This is where I get my intuitive feel for  whether drugs are good or bad. Psychedelics open you up, heroin shuts you down. But I dropped acid roughly 300 times in my late teens and early twenties. I shot heroin about 30-40 times. Why do l assume that heroin is addictive and LSD is pure sunshine?

whether drugs are good or bad. Psychedelics open you up, heroin shuts you down. But I dropped acid roughly 300 times in my late teens and early twenties. I shot heroin about 30-40 times. Why do l assume that heroin is addictive and LSD is pure sunshine? change? [But let me add this: last year I went to a neuroscience conference and learned that

change? [But let me add this: last year I went to a neuroscience conference and learned that  Why do we value control so much? Is control the wedge? Or is harm the crucial marker? Control vs harm and the history of antipsychotics…that increase control and kill the soul. Drugs that harm: don’t they require harm reduction? Or is it happiness, well-being, that’s key? Then why prescribe SSRIs when you could prescribe opiates for emotional pain? If you value control, then get this: drugs are a way to control our thoughts and feelings. Yet self-medication often leads to self-harm. How do we weigh the goodness of drugs when control, well-being, creativity, awareness and harm are all simultaneously changing variables?

Why do we value control so much? Is control the wedge? Or is harm the crucial marker? Control vs harm and the history of antipsychotics…that increase control and kill the soul. Drugs that harm: don’t they require harm reduction? Or is it happiness, well-being, that’s key? Then why prescribe SSRIs when you could prescribe opiates for emotional pain? If you value control, then get this: drugs are a way to control our thoughts and feelings. Yet self-medication often leads to self-harm. How do we weigh the goodness of drugs when control, well-being, creativity, awareness and harm are all simultaneously changing variables? Societal differences — my undergrads at Nijmegen [a rural region of the Netherlands] still see addicts as a different species; in Amsterdam students don’t see it like that. Let’s send Mr Hazelden to an ayahuasca ceremony and see how/whether he evolves.

Societal differences — my undergrads at Nijmegen [a rural region of the Netherlands] still see addicts as a different species; in Amsterdam students don’t see it like that. Let’s send Mr Hazelden to an ayahuasca ceremony and see how/whether he evolves. Why would anyone put ayahuasca in the same category as heroin…isn’t there something intrinsically valuable about perspective change, for its own sake? And what’s the difference

Why would anyone put ayahuasca in the same category as heroin…isn’t there something intrinsically valuable about perspective change, for its own sake? And what’s the difference  between methadone and SSRIs when it comes to allaying depression (yet one is for disgusting addicts and the other is for normal healthy people, like Aunt Mary). But I so disagree with Carl Hart when he says that when your teenage kid wants to try meth your only duty (and your only right) is to educate him/her about safety issues. Are the distinctions between good and bad drugs in the drugs themselves (as we often think reflexively) or in the relation between the drug and the user? We have to really get individual differences. And developmental differences. Binge drinking at 16, not so good…social drinking at age

between methadone and SSRIs when it comes to allaying depression (yet one is for disgusting addicts and the other is for normal healthy people, like Aunt Mary). But I so disagree with Carl Hart when he says that when your teenage kid wants to try meth your only duty (and your only right) is to educate him/her about safety issues. Are the distinctions between good and bad drugs in the drugs themselves (as we often think reflexively) or in the relation between the drug and the user? We have to really get individual differences. And developmental differences. Binge drinking at 16, not so good…social drinking at age  28 can really help people connect. And what I learned from [my good friend and courageous colleague]

28 can really help people connect. And what I learned from [my good friend and courageous colleague]  control. I had people coming up to me while I stood rigid, paralyzed, in the middle of a busy hotel lobby between session, and carry or drag me to the nearest sofa (it was a pretty plush hotel). And even sitting, I could not unspasm; my body seemed like a lighting rod that would not stop zapping. People I didn’t know — strangers — found me a wheelchair, wheeled me to the elevator, got me down to the street level and called a taxi to take me to the hospital. And the next day, at a doctor’s office near my own hotel, I was howling so bad that the doctor and his assistants dragged me out of the waiting room because I was scaring the other patients. They then lifted me into a taxi — back to the hospital again. When all I really needed was a shot of morphine or a substantial dose of oxycodone. Getting high was the furthest thing from my mind.

control. I had people coming up to me while I stood rigid, paralyzed, in the middle of a busy hotel lobby between session, and carry or drag me to the nearest sofa (it was a pretty plush hotel). And even sitting, I could not unspasm; my body seemed like a lighting rod that would not stop zapping. People I didn’t know — strangers — found me a wheelchair, wheeled me to the elevator, got me down to the street level and called a taxi to take me to the hospital. And the next day, at a doctor’s office near my own hotel, I was howling so bad that the doctor and his assistants dragged me out of the waiting room because I was scaring the other patients. They then lifted me into a taxi — back to the hospital again. When all I really needed was a shot of morphine or a substantial dose of oxycodone. Getting high was the furthest thing from my mind. So why couldn’t they provide that? Even at the hospital, I had to lie on a gurney intermittently screeching in pain for over an hour before the morphine came. People passing by had pity written all over their faces. Has the opioid scare infested Europe too? Not as much as the US, but yes, seemingly, to a degree.

So why couldn’t they provide that? Even at the hospital, I had to lie on a gurney intermittently screeching in pain for over an hour before the morphine came. People passing by had pity written all over their faces. Has the opioid scare infested Europe too? Not as much as the US, but yes, seemingly, to a degree. from that kind of pain as well. But of course no doctor will prescribe opioids for your depression, unless you’re getting methadone or Suboxone because you’re a “registered” addict, whatever that happens to mean in your corner of the world. Maybe just lining up at some seedy clinic, maybe being sneered at, maybe not being able to get a job, maybe having your license revoked…hell, in the Philippines it means being lined up and shot.

from that kind of pain as well. But of course no doctor will prescribe opioids for your depression, unless you’re getting methadone or Suboxone because you’re a “registered” addict, whatever that happens to mean in your corner of the world. Maybe just lining up at some seedy clinic, maybe being sneered at, maybe not being able to get a job, maybe having your license revoked…hell, in the Philippines it means being lined up and shot. When we’re in that kind of pain, and if we’re pretty sure that opioids can help relieve it, we’re trapped. We can’t get an opioid prescription for emotional relief. (Don’t get me started on “antidepressants” — SSRIs — which are so much less effective than hoped, which carry their own batch of side effects, and which require as much tapering as opioids to minimize withdrawal symptoms.) So we buy, borrow, steal, forge, or do whatever we have to do to acquire the medication that can bring us back to some semblance of normality, of peace.

When we’re in that kind of pain, and if we’re pretty sure that opioids can help relieve it, we’re trapped. We can’t get an opioid prescription for emotional relief. (Don’t get me started on “antidepressants” — SSRIs — which are so much less effective than hoped, which carry their own batch of side effects, and which require as much tapering as opioids to minimize withdrawal symptoms.) So we buy, borrow, steal, forge, or do whatever we have to do to acquire the medication that can bring us back to some semblance of normality, of peace.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments