Response to the heroin epidemic: 5. The argument for decriminalization

…by Gina Murillo (comments by “Gina”)…

So much of what we’re trying to hash out about drug courts here wouldn’t be an issue but for poor drug policy (the War on Drugs — as discussed in the comment section following the last post). The War on Drugs causes far more harm than good. I agree with Marc that Johann Hari makes that case more compellingly than just about anyone else, with the possible exception of Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance. (I’m not a huge fan of TED talks, but highly recommend his powerful talk on why we need to end the War on Drugs.)

This really all comes down to how society has been conditioned to view different substances and behaviors. Alcohol and tobacco are far from harmless, but are not only socially acceptable, they’ve both been glamorized  to one extent or another. They both kill many times more people each year than all illegal substances combined, even in the midst of the opiate “epidemic”. Yet, we manage to find

to one extent or another. They both kill many times more people each year than all illegal substances combined, even in the midst of the opiate “epidemic”. Yet, we manage to find  (admittedly imperfect) ways to deal with the harms they cause as best we can. We do this because we recognize that the harms of prohibiting these substances would likely be significantly greater than simply finding more effective ways to live with them.

(admittedly imperfect) ways to deal with the harms they cause as best we can. We do this because we recognize that the harms of prohibiting these substances would likely be significantly greater than simply finding more effective ways to live with them.

Imagine people being arrested for possessing cigarettes (one of the toughest addictions to quit and the #1 cause of preventable death in the U.S.) and facing a drug court judge with the threat of jail or a longer prison sentence for failing to quit smoking. Sure, probably fewer people would smoke and fewer would suffer debilitating disease as a result. But at what (and whose) cost? After all, if legal consequences are so effective at changing negative behaviors, why don’t we criminalize all behaviors we’d like to extinguish for society’s benefit? For another example, how about obesity courts? Health care costs attributed to obesity in the U.S. alone are staggering, with the number of deaths increasing  steadily each year — making it the #2 cause of preventable death (behind good ole’ tobacco). And the data strongly suggest that households with just one obese parent are at least twice as likely to raise obese children who are doomed to a shorter life expectancy than their parents. Using drug war logic, this ought to be as good a reason as any to criminalize obesity or the behaviors (and foods) that “cause” it.

steadily each year — making it the #2 cause of preventable death (behind good ole’ tobacco). And the data strongly suggest that households with just one obese parent are at least twice as likely to raise obese children who are doomed to a shorter life expectancy than their parents. Using drug war logic, this ought to be as good a reason as any to criminalize obesity or the behaviors (and foods) that “cause” it.

Sound crazy? That’s how crazy drug criminalization and drug courts seem to me now. Having dealt with my daughter’s heroin addiction for the past five years, it really hit me, after her most recent “relapse” (for lack of a better term) a little over a year ago, that it wasn’t so much her

Sound crazy? That’s how crazy drug criminalization and drug courts seem to me now. Having dealt with my daughter’s heroin addiction for the past five years, it really hit me, after her most recent “relapse” (for lack of a better term) a little over a year ago, that it wasn’t so much her  addiction that was causing the pain and trauma we were both experiencing as it was dealing with the woefully ineffective — and often counterproductive and EXPENSIVE — U.S. legal and treatment systems.

addiction that was causing the pain and trauma we were both experiencing as it was dealing with the woefully ineffective — and often counterproductive and EXPENSIVE — U.S. legal and treatment systems.

Whether to decriminalize or even legalize powerfully addictive drugs like heroin is a topic of ongoing heated debate. Decriminalization of the use and possession of all drugs is a no-brainer to me. Legalization is more tricky, but still requires an honest and intelligent discussion about the inherent risks and potential benefits.  Because while we labor under the delusion that prohibiting a given substance outright is the ultimate form of control, it is in fact the mechanism by which we relinquish all control to criminals, who have in turn been empowered by such policies to build massive global organizations. The only way to undercut that power is to minimize the enormous profits that are generated by prohibitionist policies.

Because while we labor under the delusion that prohibiting a given substance outright is the ultimate form of control, it is in fact the mechanism by which we relinquish all control to criminals, who have in turn been empowered by such policies to build massive global organizations. The only way to undercut that power is to minimize the enormous profits that are generated by prohibitionist policies.

Those who have considered the idea of legalization in any serious way are quick to couple it with proposals for control, which should address, at the very least, protection of minors (who are, incidentally, not protected from heroin availability at present), and, especially in  the case of opioids, prevention of leakage or diversion to others, policies for supervision and safety, and strict constraints on who might be eligible for prescriptions. One model of a successful quasi-legalization policy comes from Switzerland, which implemented heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) with great success to stem the tide of its own heroin epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Here is a brief description of the outcome from an article by Johann Hari in Huffington Post:

the case of opioids, prevention of leakage or diversion to others, policies for supervision and safety, and strict constraints on who might be eligible for prescriptions. One model of a successful quasi-legalization policy comes from Switzerland, which implemented heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) with great success to stem the tide of its own heroin epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Here is a brief description of the outcome from an article by Johann Hari in Huffington Post:

Switzerland also had a huge heroin crisis. Under a visionary president — Ruth Dreifuss — they decided to try an experiment. If you are a heroin addict, you are assigned to a clinic, and you are

given your heroin there, for free, where you use it supervised by a doctor or nurse. You are given support to turn your life around, and find a job, and housing.

The result? Nobody has died of an overdose on legal heroin — literally nobody. Street crime fell significantly. The heroin epidemic ended. Most legal heroin users choose to reduce their dose and come off the program over time, because as they find work, and no longer feel stigmatized, they want to be present in their lives again.

I would clarify Hari’s description further by pointing out that (1) while Switzerland didn’t legalize heroin, per se, it did make it de facto legal for a very specific subset of the heroin-using population; (2) HAT is a treatment of last resort offered only to those for whom all other methods of treatment have failed; and (3) most HAT patients actually become re-engaged in their lives once stabilized on HAT, regardless of whether they ultimately choose to taper off.

HAT has been so effective in Switzerland that it’s no longer even controversial there, and HAT trials have been implemented in a growing number of European countries and Canada. Very recently, a couple of forward-thinking lawmakers have even made attempts to introduce legislation that would authorize HAT trials in Nevada and Maryland.

I dream of the day our society can, in the inimitable words of Ethan Nadelmann, learn how to live with drugs sensibly, so that they cause the least possible harm and produce the greatest possible benefit to all. Because if there’s one thing we need to recognize, it’s that drugs aren’t ever going to go away, no matter how many laws we pass or how many people we put in jail.

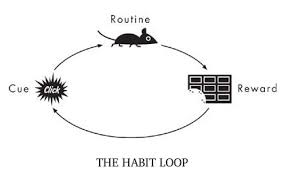

even as the desires and expectancies continue to strengthen. Is that pathological? No more than being in love with a hurtful partner, or praying to an unresponsive god, or being devoted to a sports team despite their string of losses. When the power of a reward arises from strong emotions and needs, the tendency to pursue it isn’t rational. When we seek and find that thing again and again, then, through learning,

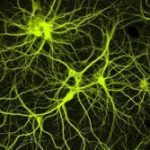

even as the desires and expectancies continue to strengthen. Is that pathological? No more than being in love with a hurtful partner, or praying to an unresponsive god, or being devoted to a sports team despite their string of losses. When the power of a reward arises from strong emotions and needs, the tendency to pursue it isn’t rational. When we seek and find that thing again and again, then, through learning,  the synapses of our brain form into dense networks (pathways of connected neurons) that become very difficult to circumvent. Learning on overdrive, through repetitive need-satisfaction, is habit formation — addiction is a deep and insidious habit.

the synapses of our brain form into dense networks (pathways of connected neurons) that become very difficult to circumvent. Learning on overdrive, through repetitive need-satisfaction, is habit formation — addiction is a deep and insidious habit. expectancies and emotions become attached to a specific goal, leading to behaviours that are partly automatic — and partly not. Habit formation results in automaticity, sensitization to some rewards, and desensitization to others. The brain changes seen in addiction are just the biological underpinnings of this natural learning progression. And…they can continue to update; they’re not carved in stone.

expectancies and emotions become attached to a specific goal, leading to behaviours that are partly automatic — and partly not. Habit formation results in automaticity, sensitization to some rewards, and desensitization to others. The brain changes seen in addiction are just the biological underpinnings of this natural learning progression. And…they can continue to update; they’re not carved in stone. But what blows me away conceptually is how this narrowing of the available, reachable, usable social environment precisely parallels the narrowing going on in one’s brain. My synapses fell in line, in pathways and networks that had a single purpose, so to speak, rather than multiple pathways supporting

But what blows me away conceptually is how this narrowing of the available, reachable, usable social environment precisely parallels the narrowing going on in one’s brain. My synapses fell in line, in pathways and networks that had a single purpose, so to speak, rather than multiple pathways supporting  multiple purposes. This “narrowing” in the brain corresponded with a shrinking or narrowing in my available environment. Neither is pathological. Both, especially both together, create a kind of prison.

multiple purposes. This “narrowing” in the brain corresponded with a shrinking or narrowing in my available environment. Neither is pathological. Both, especially both together, create a kind of prison.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments