When is “controlled drinking” possible?

…by James Morris…

The great “controlled drinking” debate has a controversial history dating back to the 1960’s. Since then, politics, addiction ideology, and evidence have often been hard to separate. In the 1970’s the Sobells were vilified for allegedly skewing the results of research showing that some dependent drinkers achieved controlled drinking, but they were later cleared of any wrongdoing. Audrey Kishline, the founder of Moderation Management (a peer support group), committed suicide after driving drunk and causing a fatal car crash. This tragic event is often cited as an example of how moderation doesn’t work.

Today, recognition of non-abstinence-oriented outcomes is less controversial. However, there is still no shortage of opponents, and not just amongst 12-steppers. Like many complex issues, the “truth” about controlled drinking may depend on which way you cut the cake.

I first became interested in this subject when after many years of abstinence I began to ask myself “could I re-learn to drink?” My relationship with alcohol had started in my early teens and then steadily  progressed; by the time I was in my early twenties I drank as much as possible, often to the point of blackout, and was experiencing physical health problems. After a number of failed attempts to cut down, I began to realise I wasn’t in control. I remember thinking to myself “if I don’t act on this now, where will it end?”

progressed; by the time I was in my early twenties I drank as much as possible, often to the point of blackout, and was experiencing physical health problems. After a number of failed attempts to cut down, I began to realise I wasn’t in control. I remember thinking to myself “if I don’t act on this now, where will it end?”

Stopping drinking in my twenties was very difficult. During my early months of sobriety I struggled to stop thinking about alcohol and battled with trying to reformulate my identity and social life. Drinking pressures and cues seemed to surround me constantly, but in some ways this made me more determined.

As time passed things slowly became easier and more normal as a “non-drinker,” though initially I sought various other pursuits to try and fill the excitement gap. I also attended AA meetings for a while. Generally I found the meetings positive and could identify with a lot of what I heard, though ultimately I never felt I was powerless and therefore an “alcoholic.”

Around six years later I felt like I was in a very different place, settled with a rewarding job, happier in myself as a person and as a “non-drinker.” During this time psychotherapy helped a lot, especially with  anger issues connected with my past drinking. I began to feel things were so different now that normal drinking might be possible, and after a few years of contemplation, I eventually decided to see if I could “re-learn” a problem-free relationship with alcohol.

anger issues connected with my past drinking. I began to feel things were so different now that normal drinking might be possible, and after a few years of contemplation, I eventually decided to see if I could “re-learn” a problem-free relationship with alcohol.

Many people still believe anyone with an alcohol addiction can never drink again without slipping back into old habits. The disease model of addiction as a “chronic relapsing condition” and associated beliefs about “alcoholics” are deeply entwined with the idea that abstinence is the only genuine option for long-term recovery.

There are some valid reasons to be skeptical of controlled drinking for once-dependent drinkers. Long-term studies suggest only a minority of problem drinkers achieve controlled or problem-free drinking, and for people with severe alcohol addiction, abstinence is usually identified as the most successful route. Indeed, severity of dependence is a central theme in addiction theory and in the concept of “alcohol dependence syndrome” that underpins ICD-10 and DSM classifications. Even so, some controlled-drinking studies have observed success in a subset of drinkers with more severe dependence. Whilst some argue that those with less severe dependence are not really “addicted,” there is no scientifically valid cut-off point.

In fact, the role of severity of dependence as a predictor of controlled drinking is unclear. Some studies have found other measures, like the extent of “impaired control” — i.e. failing to limit one’s drinking — serve as better predictors. Another important factor may be a period of abstinence. A drinker who has had many years without drinking will be more likely to succeed than one who simply tries to cut down straight away. How much of this may be about the brain “un-learning” drinking reward pathways — and how much may be about life changes and other skills that sobriety brings about — is again hard to generalise.

I began controlled drinking six years ago, and despite anxieties that I was doing the wrong thing, there are no signs that my relationship with alcohol has become problematic again. I might drink three times a week, typically with a meal, on weekends, or out with friends, and not more than two or three drinks on an occasion — within the UK’s recommended guidelines.

I began controlled drinking six years ago, and despite anxieties that I was doing the wrong thing, there are no signs that my relationship with alcohol has become problematic again. I might drink three times a week, typically with a meal, on weekends, or out with friends, and not more than two or three drinks on an occasion — within the UK’s recommended guidelines.

However, comparing myself then and now feels like comparing two different people. Then I was young and in many ways insecure, anxious and with a lot of fire in my belly. Drinking always felt like it allowed me to let go of this nervous energy. I believe that working through past issues through psychotherapy was as crucial as my long period of abstinence. I strongly feel that this process helped me deal with issues that fuelled my destructive drinking.

Trying to answer “when is controlled drinking possible?” is a bit like asking “what’s the best treatment for addiction?” — there are no easy answers; it depends on many factors. But there are some basic principles that might help predict success. Fundamentally, it may be fair to generalise that controlled drinking tends to be less successful for people who’ve been more severely dependent, experienced adverse childhood experiences, previously failed to control their drinking, or endured excessive insecurity or stress in their lives.

To anyone with a history of alcohol problems contemplating controlled drinking, I would suggest they ask themselves what it is they truly want or expect from drinking again. Weighing up the pros and cons  objectively can be difficult, and it can be easy to over-value the pleasurable effects of moderate drinking. For me alcohol may have a mild relaxant effect, but it is not to de-stress, let go, or suppress negative emotions. If I go through a tough time in the future, I believe that will be an important time not to drink. Keeping healthy and looking after myself in other ways provide protective effects that allow me to drink without problems.

objectively can be difficult, and it can be easy to over-value the pleasurable effects of moderate drinking. For me alcohol may have a mild relaxant effect, but it is not to de-stress, let go, or suppress negative emotions. If I go through a tough time in the future, I believe that will be an important time not to drink. Keeping healthy and looking after myself in other ways provide protective effects that allow me to drink without problems.

The author is in no way encouraging those with former alcohol problems to attempt “controlled drinking.” The author wishes to reiterate that controlled drinking is not suitable for many drinkers who seek help for alcohol problems, and anyone considering controlled drinking should consider the possible benefits of professional help.

Then I started to work in harm reduction. I founded a SMART Recovery meeting, and went on to become an officer in the

Then I started to work in harm reduction. I founded a SMART Recovery meeting, and went on to become an officer in the  withdrawing from alcohol more times than I can count, sometimes throwing up blood for days on end and nailed to the bed in a panic attack. I didn’t even want to remember those early days of abstinence when my senses first came back and I could smell the flowers in summer and taste blueberries and coffee as though for the first time.

withdrawing from alcohol more times than I can count, sometimes throwing up blood for days on end and nailed to the bed in a panic attack. I didn’t even want to remember those early days of abstinence when my senses first came back and I could smell the flowers in summer and taste blueberries and coffee as though for the first time. After almost two years and working with countless people with substance use problems, I could feel my own pain again. And I realized something: to deny that there is a period of time when the pain is acute, and when healing has to be a priority, is to deny an essential reality of people’s lives. Of my own life. That’s when I started to use the word “recovery” again. But I do not believe that “recovery” is a permanent state. With proper self-care, support, and meaning in life, one can heal.

After almost two years and working with countless people with substance use problems, I could feel my own pain again. And I realized something: to deny that there is a period of time when the pain is acute, and when healing has to be a priority, is to deny an essential reality of people’s lives. Of my own life. That’s when I started to use the word “recovery” again. But I do not believe that “recovery” is a permanent state. With proper self-care, support, and meaning in life, one can heal. rehab, we were taught to identify as “addict” and “alcoholic,” and told that all our problems were due to our “disease.” We did little to address the issues that drove our addiction. Instead, we were taught that the answer to all problems was to attend Twelve Step meetings and work the Steps.

rehab, we were taught to identify as “addict” and “alcoholic,” and told that all our problems were due to our “disease.” We did little to address the issues that drove our addiction. Instead, we were taught that the answer to all problems was to attend Twelve Step meetings and work the Steps. As I read more, I gradually began to discover my own voice, and started to write. Reclaiming my own identity, not as an “alcoholic” but as a writer, activist and scholar was my way out, not only of addiction but of the narrow, confined life that rehab and AA had defined for me as “recovery.” And I found that my own painful experiences gave me a perspective that could help others. Today, having recovered means living a life that I don’t have to medicate away.

As I read more, I gradually began to discover my own voice, and started to write. Reclaiming my own identity, not as an “alcoholic” but as a writer, activist and scholar was my way out, not only of addiction but of the narrow, confined life that rehab and AA had defined for me as “recovery.” And I found that my own painful experiences gave me a perspective that could help others. Today, having recovered means living a life that I don’t have to medicate away.

I’ll spare you all the usual listing of what’s wrong in the world, from Brexit, to the right-wing populist movements sweeping Europe, to Trump. Well I guess I didn’t spare you. But for me what it comes down to with Trump is pretty simple. He’s a liar and a cheat. Almost everything he says is a lie. He replaces it the following week or the following day — usually with another lie. And most of his campaign promises were mere strategic gambits to win votes. He’s not going to build a wall, or prosecute Hillary. Who ever imagined that he would? He’s even talking about taking a serious look at climate change and maybe endorsing the Paris Accord, which is of course good news. It’s just a shame that he got voted in on his promise to ignore the environment because climate change is a fantasy promoted by the Chinese.

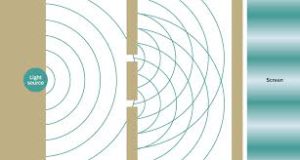

I’ll spare you all the usual listing of what’s wrong in the world, from Brexit, to the right-wing populist movements sweeping Europe, to Trump. Well I guess I didn’t spare you. But for me what it comes down to with Trump is pretty simple. He’s a liar and a cheat. Almost everything he says is a lie. He replaces it the following week or the following day — usually with another lie. And most of his campaign promises were mere strategic gambits to win votes. He’s not going to build a wall, or prosecute Hillary. Who ever imagined that he would? He’s even talking about taking a serious look at climate change and maybe endorsing the Paris Accord, which is of course good news. It’s just a shame that he got voted in on his promise to ignore the environment because climate change is a fantasy promoted by the Chinese. If there’s anything useful I can say at the moment, it’s to suggest we look at the present glut of bad news as waves rather than particles. Sounds spiffy to use quantum terms. Waves seem like tendencies, currents, gusts…in a universe that is constantly in flux. Whereas particles…give the sense of matter, substance, stuff

If there’s anything useful I can say at the moment, it’s to suggest we look at the present glut of bad news as waves rather than particles. Sounds spiffy to use quantum terms. Waves seem like tendencies, currents, gusts…in a universe that is constantly in flux. Whereas particles…give the sense of matter, substance, stuff  that collects in corners until there’s so much of it you really have to rent heavy machinery to get rid of it. So when the Buddha talked about impermanence as the main act, maybe he was thinking more in terms of waves than particles. Impermanence actually seems like good news at the moment.

that collects in corners until there’s so much of it you really have to rent heavy machinery to get rid of it. So when the Buddha talked about impermanence as the main act, maybe he was thinking more in terms of waves than particles. Impermanence actually seems like good news at the moment. I sometimes wonder what’s at the core of all these right-wing leanings. Let’s preserve what we’ve got. Let’s keep America American. Let’s maintain our way of life because it’s being threatened. Damn right your way of life is being threatened because….get ready…you’re going to die! What could be more threatening to anyone’s way of life?

I sometimes wonder what’s at the core of all these right-wing leanings. Let’s preserve what we’ve got. Let’s keep America American. Let’s maintain our way of life because it’s being threatened. Damn right your way of life is being threatened because….get ready…you’re going to die! What could be more threatening to anyone’s way of life? breathing steam, I think: this is just fine. This is a great moment. This wish to preserve things the way they’ve always been (as if that were a good thing)… What’s the point of that?

breathing steam, I think: this is just fine. This is a great moment. This wish to preserve things the way they’ve always been (as if that were a good thing)… What’s the point of that? Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments