Addiction, co-occurring conditions, and Humanity 101

If you’re a regular on this blog, you probably know that Peter Sheath and Matt Robert have enough knowledge, compassion, and common sense about addiction and recovery to lead us to a far far better world. I’ve grabbed these gems from their comments to a recent post. If you’ve already read them in context, well read them again. If not, now’s your chance.

Peter Sheath:

I feel like there is an amazing amount of synchronicity going down, especially between you [Marc], Matt and li’l ol’ me. I can almost guarantee that I will have had my interests stimulated by a client, book, lecture or simply talking to someone and, a few days later it will be there in your blog and Matt will have made one of his beautifully eloquent comments on it. This may not sound so apparent at first but please bear with me.

I feel like there is an amazing amount of synchronicity going down, especially between you [Marc], Matt and li’l ol’ me. I can almost guarantee that I will have had my interests stimulated by a client, book, lecture or simply talking to someone and, a few days later it will be there in your blog and Matt will have made one of his beautifully eloquent comments on it. This may not sound so apparent at first but please bear with me.

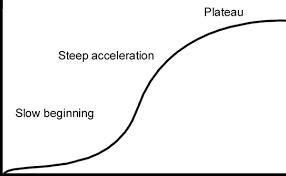

Over the past couple of years I’ve been doing a lot of thinking, talking and research around this whole co-occurring conditions/dual diagnoses thing. I think we, organisationally, have got astonishingly good at not dealing with it. We love to have these imaginary silos that we place people into, develop manuals and protocols to either keep them there or embargo them from going there. We’ve even developed competency/accountability frameworks, skill-sets and governance systems that ensure that, supposedly, the right person is working with the right person, at the right time, in the right place.

The trouble is that it mainly creates confusion, uncertainty, apartheid and exclusivity. Only the other day I received a phone call from a friend who is managing a substance misuse team for people with complex needs. He had been asked to develop a “criteria” for the people his team would be working with. I said that I’m very sorry but I really do not believe in having criteria for people we do or don’t work with and everybody who comes to substance misuse services for help will have complex needs. Turns out that he is of exactly the same mind but has to do it because that’s what he’s been instructed to do.

Doing things in this way means that we often screen more people out than we do in and I have real difficulties understanding why we continue to do it. Jordan Peterson’s 12 rules for life, motivational interviewing, open dialogue, ACT, CBT, person-centred counselling, narrative exposure, etc. are all transdiagnostic and probably work best under the collective umbrella of the therapeutic relationship.

I’m currently working with a paying client who has had a lifetime of psychiatric diagnoses and various dependencies. He came to me because he had approached his local alcohol service looking for a community alcohol detox. The detox would need to fit around his work, because he works for himself and is the only employee. He was drinking at least a 750-ml bottle of vodka every day and was getting increasingly desperate and depressed. The service said that, because of his underlying mental health problems, levels of alcohol use and not being able to take time off work they couldn’t help him! I know it beggars belief, doesn’t it? I negotiated a course of Librium with his GP, involved his mother and his local pharmacist in the plan (open dialogue), then did some motivational interviewing type interventions to boost his confidence and ensure that getting sober was the right thing to do. We arranged a daily telephone check-in and weekly face to face, with myself, and I taught his mum and him how to do blood pressure monitoring. He agreed to call in to the pharmacy if his BP raised or reduced by 10.

Got a phone call last night to say that his detox had finished a week ago and he is now 21 days sober. He has struggled a bit because the weather over here has been lovely and he has an association with sunny days and sitting outside the pub drinking beer. He has used some psychotropic meds sparingly, because he does get worried about his anxiety levels, panic attacks and past psychoses. I’ve also been teaching him mindfulness-based meditations, relapse prevention and managing his mental health. We’ve developed a really good therapeutic relationship based on trust, autonomy, prosocial role modelling and hope. We’ve also focused on very small steps, although he is always wanting to make massive leaps. Fingers crossed.

Matt Robert:

Hey Peter!! It keeps coming back to this, doesn’t it? It takes a village…but a coordinated one that meets the needs of the individual as well as the tribe. Your sentence captures it all:

Hey Peter!! It keeps coming back to this, doesn’t it? It takes a village…but a coordinated one that meets the needs of the individual as well as the tribe. Your sentence captures it all:

“We’ve developed a really good therapeutic relationship based on trust, autonomy, prosocial role modelling and hope.”

There has to be autonomy, agency… individuals need to feel in control or we don’t feel safe. I have to trust my fellow participants, the method, the goal, because I’m not going to stick with a process of arduous change if I don’t believe in it. And none of it is gonna work if I don’t feel like I’m in a sharing, connected, reciprocal relationship with the humans who are helping me. Something all effective recovery traditions have in common. All human endeavor, for that matter.

The thing about open dialogue that is so simple and compelling is that it is the same model humans have used to cooperate, help each other, and progress throughout history. It’s getting all the stakeholders, the people who care, in the same room, on the same page. It’s putting the puzzle that’s fallen apart back together.

We all know how to do this because it is a human thing, not an “addiction” thing. Addiction is a proxy for meaningful relationship.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments