Response to the heroin epidemic: 3. OST, the economics of diversion, and the dangers of naltrexone

…by Shaun Shelly…

Percy Menzies’ post has stirred up a lot of controversy! Here, Shaun’s extensive rebuttal gathers some of these arguments, plus many of his own, and launches them in torpedo-like fashion. Shaun’s command of the research landscape is awesome, but let’s take care to keep a balanced perspective.

…………………………………

In the previous post on this site Percy Menzies makes what appears to be a persuasive argument for naltrexone as a favourable intervention when addressing heroin use disorders. Where Dr. Menzies and I agree is that people who have a heroin use disorder should have a wide range of options for treatment, all the way from non-pharmaceutical to antagonist to agonist. Having said this, I have some major problems with his argument, and I believe that the promotion of naltrexone as a valid response to the heroin epidemic, compared to agonist and partial agonist therapies, is flawed.

The first thing we need to know is that opioid substitution therapy (OST) works. It is the gold standard recommended by the World Health Organisation, and for the last 50 years methadone has been proven to reduce mortality, reduce crime, improve health, improve retention in treatment and allow people the space to resolve  many of the issues that have made drug use so meaningful to them. It also reduces the spread of HIV. Through robust head-to-head clinical trials, buprenorphine has also been shown to be effective, in some cases more so, in some cases less, but it is effective and has a better safety profile.

many of the issues that have made drug use so meaningful to them. It also reduces the spread of HIV. Through robust head-to-head clinical trials, buprenorphine has also been shown to be effective, in some cases more so, in some cases less, but it is effective and has a better safety profile.

Dr. Menzies suggests that the treatment of heroin use disorders is “overwhelmingly dominated” by OST. This is simply not true. According to a 2015 SAMHSA report, only 22% of people between the ages of 22 and 34 accessing treatment for heroin use disorders received OST. Even judges playing doctor are ordering people to stop OST. Further, Dr. Menzies argues that if OST was made more available it would “exacerbate the existing problem, as the pool of opioids will greatly increase along with abuse and diversion.” The data simply do not support this: In Switzerland, where 92% of people in heroin use treatment are receiving agonist therapies, the number of people with a heroin use disorder is dropping by 4% per year and no one has died from a heroin overdose since the programme was started in the early 90s. Similarly in France, where buprenorphine is the norm, 70% of heroin users have access to OST and there has been an 80% reduction in heroin-related deaths and a 75% drop in HIV prevalence among injecting drug users. 20% of French physicians prescribe buprenorphine compared to 3% in the US.

As far as diversion is concerned, diversion is a function not of greater availability but of lack of availability. The diversion of methadone and buprenorphine occurs because they have a street value — because people cannot access these medications or because the services that offer them are not attractive to them. This is basic economics, and it has been proven throughout history. Increased access through appropriate services will reduce diversion!

As far as diversion is concerned, diversion is a function not of greater availability but of lack of availability. The diversion of methadone and buprenorphine occurs because they have a street value — because people cannot access these medications or because the services that offer them are not attractive to them. This is basic economics, and it has been proven throughout history. Increased access through appropriate services will reduce diversion!

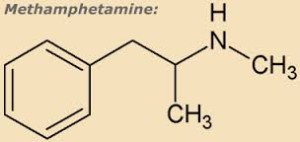

The most concerning aspect of Dr. Menzies argument is his promotion of naltrexone in lieu of OST. Naltrexone has been available since 1984 in the oral form for treating opioid dependence and XR-NTX, the extended release injectable version, since 2010. Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist. In other words it has affinity with the opioid receptor but has no intrinsic value and therefore no efficacy. Theoretically this blockage causes the dissipation of Pavlovian learning over time. But for this to occur, the naltrexone needs to be taken over time, and retention and compliance are listed as a major problem in all the studies. The 28-day injection (XR-NTX) was developed, and this has improved compliance, but in many studies patients do not complete the course — in a phase four trial only 36% of participants completed the treatment. Dr. Menzies and his organisation, Assisted Recovery Centers of America (ARCA), also describe naltrexone as an anti-craving medication on their website. But what does the data say?

A Cochrane and other reviews have shown that naltrexone performs no better than placebo in reducing heroin use. Craving has only been shown to be reduced with the XR-NTX formulation, but studies suggest this is linked to period of abstinence independent of the drug. Further, due to the antagonist nature and subsequent upregulation of opioid receptors, once naltrexone is stopped it significantly increases the risk of overdose. Some studies have suggested that this risk can be 7 times higher than with methadone.

Further, the studies that were used to secure FDA approval for XR-NTX in the treatment of heroin use disorders were done in Russia, where OST is outlawed. It is a basic principle of clinical trial ethics that if there is an existing treatment option, placebo controlled trials are not ethical. There have been no head-to-head trials in the US for naltrexone vs. OST. A Malaysian trial ended prematurely because the difference between buprenorphine and naltrexone was so great that it would not have been ethical to continue!

Dr. Menzies is suggesting that we use a medication that has: not been through head-to-head clinical trials with a known effective treatment (OST); that performs no better than placebo unless autonomy is taken away and it is given in a 28-day formulation; and that has been shown to significantly increase the risk of mortality on termination. He further suggests that it may be especially useful for “patients who are not well-to-do and who are, as a result, often trapped in a very limited set of choices.” This despite the recommendations of the World Health Organisation and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommending that only employed, fully informed, short-term users who want total abstinence and are well informed of the consequences of naltrexone would benefit. Studies looking at retention and efficacy have shown that people who are homeless, injectors, or have co-occurring disorders are not suited to naltrexone. At US$1000 a shot, I wonder how long the “not well-to-do” will be compliant.

In the interests of autonomy, disclosure and choice, naltrexone should be on the menu, as Dr. Menzies suggests. But based on the evidence, Dr. Menzies’ post promoting naltrexone as the most promising response to the heroin epidemic appears to be less of a reasoned argument and more of a biased stance that capitalises on the fear and stigma so many have towards opioids and those who use them.

For a more complete argument against the use of naltrexone, complete with references, please see my piece in The Influence.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments