An alternative to abstinence: Craving, care, and harm reduction

At the heart of the discussion about addiction and recovery lies a trilogy of questions: whether abstinence is necessary or even helpful, what “harm reduction” offers in its place, and what is the best way to deal with cravings. These questions are intertwined. In fact they merge into a single issue. Today I want to approach this issue from the perspective of part-selves, and look more closely at harm versus care.

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of  the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be?

the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be?

Those are “parts” we recognize most easily. But according to IFS, Internal Family Systems therapy, there can be many more parts to us. I wanted to be at an IFS workshop this week. I’d paid the fee, bought my ticket to Bristol,  reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later.

reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later.

For now, here’s my take on the parts:

Clearly craving is the single biggest challenge to people who want to overcome their addiction. The recommended methods to deal with cravings are (1) urge surfing — watching the craving come, peak, and then dissipate, while maintaining a mindful objectivity, and (2) developing new thought patterns, usually with the help of others, that result in abstinence until the cravings subside over time (or, less optimally, “white-knuckling” until you can start to relax). If these work for you (or your friend, family member, client) then that’s just great. And sometimes, when the consequences of substance use are dire and immediate, abstinence may be the only sensible choice.

But abstinence has a huge drawback. It’s incredibly difficult! It can feel like turning your back on your best friend, on love and comfort, forever! It can feel like kissing goodbye to the one thing in your life you could control — changing  how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease.

how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease.

Abstinence erects a steel fence around the part of us that wants and feels it needs to get high (or get full, in eating disorders). But what if we were to take  that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated.

that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated.

The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes.

The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes.

So, instead of banishing that part, in IFS and other psychodynamically-oriented approaches (including ACT and my own cobbled-together approach), the idea is to listen to the craving and connect with it. Can there be value in this?

It’s such an outlandish idea in many people’s minds, that I’m not at all sure this approach gets tested very often. (Research on IFS is still in its early stages.) But I’ve seen it work with some of my clients. And obviously I’m still developing the relevant skills.

Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else.

Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else.

Connecting with cravings doesn’t mean you have to be stupid about it, run out of your apartment and score as much coke as you can snort. In fact, being smart about cravings is one way to hold and soothe the part-self that feels so needy.

But the benefit of accepting and embracing the needy part isn’t just scaffolding it and keeping it from tearing the house down. Its greatest benefit is the feeling  of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in

of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in  your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction.

your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction.

And when the need is no longer desperate and isolated, that’s when you can manage to count your drinks, call a friend, watch a movie instead, shift from whiskey to wine (my target these days — I’m down to one scotch and a glass of wine most nights) …and taper, gradually — develop a schedule of controlled use or stop entirely. Once you feel less fragmented, once the warring factions have laid down their arms, you might find that place much more accessible, and it’s a lot less likely to give way when life throws its next curve-ball…or its next virus.

To me, this is harm reduction. Specifically, a psychological approach to harm reduction that makes sense and feels right.

……………………..

People, please please click on this link to my (new and improved!) YouTube channel, where many videos of me blathering are neatly arranged and clickable. And please consider subscribing, for newly posted talks and interviews. (No junk mail, I promise.) I need to get more traffic to this site and increase the number of subscribers if it’s ever going to show up in Google searches.

People, please please click on this link to my (new and improved!) YouTube channel, where many videos of me blathering are neatly arranged and clickable. And please consider subscribing, for newly posted talks and interviews. (No junk mail, I promise.) I need to get more traffic to this site and increase the number of subscribers if it’s ever going to show up in Google searches.

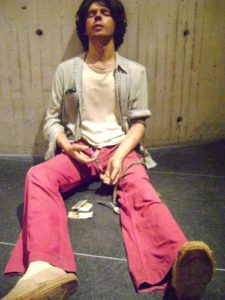

My first year in Berkeley, California. It’s 1968-69. The sun is shining, exotic flowers and trees line the streets, the hippie types (including me, sort of) wear their colourful clothes with playful exuberance. There were smiles on many faces. Fascinating men, beautiful women. We felt like we were ushering in a new age of humanity, a real cultural revolution.

My first year in Berkeley, California. It’s 1968-69. The sun is shining, exotic flowers and trees line the streets, the hippie types (including me, sort of) wear their colourful clothes with playful exuberance. There were smiles on many faces. Fascinating men, beautiful women. We felt like we were ushering in a new age of humanity, a real cultural revolution. But I was lost. I wandered the streets feeling empty and unreal. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Depression crashed down on me every evening I was alone — that is, without my roommate or my part-time girlfriend, Susan. I had a very hard time being with family members, because I felt there was something deeply wrong with me, beneath contempt. I resented the walls of politeness that seemed to shut me out of their lives. I lived in a pool of shame that was almost impossible to sense clearly because it was so constant. I have no doubt that my traumatic experience created or refined this part of me — broken, shamed, empty.

But I was lost. I wandered the streets feeling empty and unreal. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Depression crashed down on me every evening I was alone — that is, without my roommate or my part-time girlfriend, Susan. I had a very hard time being with family members, because I felt there was something deeply wrong with me, beneath contempt. I resented the walls of politeness that seemed to shut me out of their lives. I lived in a pool of shame that was almost impossible to sense clearly because it was so constant. I have no doubt that my traumatic experience created or refined this part of me — broken, shamed, empty. But there was one way to feel better, to feel…vital. Drugs. You can bet there were a lot of drugs available in Berkeley in those days. And they worked. From cannabis I went to psychedelics, acid two or three times a week, riding my motorcycle through thickets

But there was one way to feel better, to feel…vital. Drugs. You can bet there were a lot of drugs available in Berkeley in those days. And they worked. From cannabis I went to psychedelics, acid two or three times a week, riding my motorcycle through thickets  of hallucinations, and then from psychedelics to heroin, and then on to pharmaceuticals and crime. Check out my first book on addiction —

of hallucinations, and then from psychedelics to heroin, and then on to pharmaceuticals and crime. Check out my first book on addiction —  Now, when my meditation leads me to my wounded parts, I greet that 17-year old kid and let him know that it’s not his fault, that I accept him completely — him and his 12-year spree of crime and self-abuse — and that I love him. I let him know that he doesn’t have to live in that crazy, tilted world anymore. And that’s all he needs, that acceptance and care. It heals him.

Now, when my meditation leads me to my wounded parts, I greet that 17-year old kid and let him know that it’s not his fault, that I accept him completely — him and his 12-year spree of crime and self-abuse — and that I love him. I let him know that he doesn’t have to live in that crazy, tilted world anymore. And that’s all he needs, that acceptance and care. It heals him.

to have a NTX implant, to increase the chances that they would get through the crucial and often difficult first couple of months, when relapse rates are highest. We did around 2000 home detoxes before one family fatally misunderstood the instructions. Naturally, I feel bad about that but I don’t feel bad about trying to devise affordable treatment. I think that case made the difference between a reprimand and being removed from the register, but many addiction clinicians and academics in Britain (and several abroad who gave evidence for me) will tell you that the establishment were out to get me and were looking for excuses.

to have a NTX implant, to increase the chances that they would get through the crucial and often difficult first couple of months, when relapse rates are highest. We did around 2000 home detoxes before one family fatally misunderstood the instructions. Naturally, I feel bad about that but I don’t feel bad about trying to devise affordable treatment. I think that case made the difference between a reprimand and being removed from the register, but many addiction clinicians and academics in Britain (and several abroad who gave evidence for me) will tell you that the establishment were out to get me and were looking for excuses. If Marc thinks I look a bit weird in some of the online images, that’s probably because they were taken when I was trying to force my way through a rat-pack of paparazzi after the final hearing. Fortunately, the clinic I set up continues and is still doing most of the things that we had been doing up to the hearings. Some of those — e.g. using slow-release morphine for people who don’t get on well with methadone or buprenorphine — are now pretty normal, at least outside the USA. The clinic is also expanding its patient groups to include the growing problem — though it’s still small by US standards — of prescription opiate abuse and the management of ‘therapeutic addiction’ to opiates in pain problems. I only have an advisory role these days but we hope to extend what Emmanuel and I suggested should be called ‘Antagonist-Assisted Abstinence’ (AAA – geddit?) to benzodiazepines. Using s/c or slow i/v flumazenil infusions, it’s quite easy to take people off fistfuls of diazepam and other benzodiazepines in five days with very little discomfort, and a flumazenil implant is being developed in Australia.

If Marc thinks I look a bit weird in some of the online images, that’s probably because they were taken when I was trying to force my way through a rat-pack of paparazzi after the final hearing. Fortunately, the clinic I set up continues and is still doing most of the things that we had been doing up to the hearings. Some of those — e.g. using slow-release morphine for people who don’t get on well with methadone or buprenorphine — are now pretty normal, at least outside the USA. The clinic is also expanding its patient groups to include the growing problem — though it’s still small by US standards — of prescription opiate abuse and the management of ‘therapeutic addiction’ to opiates in pain problems. I only have an advisory role these days but we hope to extend what Emmanuel and I suggested should be called ‘Antagonist-Assisted Abstinence’ (AAA – geddit?) to benzodiazepines. Using s/c or slow i/v flumazenil infusions, it’s quite easy to take people off fistfuls of diazepam and other benzodiazepines in five days with very little discomfort, and a flumazenil implant is being developed in Australia. months off for withdrawal — are being put on forced reductions. I never claimed to be perfect (as we say in the trade, ‘if you haven’t made any mistakes. you’re not seeing enough patients’) but I don’t think that anything I did caused remotely as much misery and disaster to opiate addicts as the policies encouraged by the addiction establishment in the face of mounting evidence for the value of methadone-maintenance treatment.

months off for withdrawal — are being put on forced reductions. I never claimed to be perfect (as we say in the trade, ‘if you haven’t made any mistakes. you’re not seeing enough patients’) but I don’t think that anything I did caused remotely as much misery and disaster to opiate addicts as the policies encouraged by the addiction establishment in the face of mounting evidence for the value of methadone-maintenance treatment. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments