How to fight addiction in the season of Covid-19

Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open!

Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open!

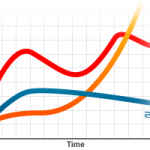

In my last scientific article on addiction and recovery, I set out a new and improved model of addiction (described in more detail here). I looked at addiction as a “narrowing” of the brain — a setting and solidification of neural networks focused on drug rewards — paralleled by a narrowing of the (available, meaningful) social environment.

This is not rocket science, or even brain science.

The main trouble with the “brain disease model” of addiction is that it ignores the massive impacts of the social environment. Yet we know that emotional challenges create the predisposition to later addiction. We know that the social environment (including one’s family history) matters hugely. We know that abuse (including emotional abuse) and neglect during our growing-up years are by far the best predictors of addiction in adulthood. The brain disease model simply can’t make sense of these facts. How could a brain disease develop from hard times growing up?

So in my model I emphasize that harmful social experiences have a shrinking or narrowing effect. If caregivers or peers make you feel off or wrong or insecure, or unable to trust, unable to just be, then you ingest what gives you the next best thing. Something that  soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain.

soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain.

The social shutdown isn’t just in the words and deeds you receive from people you know. It’s also a reduction in the places you go, activities, walks in the park, the freedom to be buffeted by babbling crowds shopping, living, watching, listening. When drink or drugs seem all that’s available to provide what you need, you let go of other possible sources of pleasure and satisfaction, energy, and identity. They were never that reliable to begin with. And before long you forget about them, you forget how to find them, you forget they even exist. That’s what locks addiction in place.

It’s what Johann Hari wrote about in Chasing the Scream: the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety; it’s connection.

So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile.

So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile.

Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems.

Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems.

For those who are taking care of kids who are also stuck at home, the increased contraction of possibilities is laced with stress. You have to attend to these little buggers all day long. You love them,  okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not

okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not  only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect.

only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect.

So here’s what you should do. If you’re trying to quit or control substance use (or other addictive activities — porn, online gambling, whatever), get your ass out of the house! Social distancing doesn’t mean solitary confinement. Here in my city in the Netherlands, I’ve seen more and more people strolling over the last two or three weeks. People walk, and when they’re about to pass by, either they or you or most likely both of you move aside, so there’s a good two meters (six feet) separation. That separation doesn’t prevent, in fact it seems to enhance, people’s tendency to smile at each other, say Hi, wave, even utter a few words of greeting.

And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask

And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask  about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

Getting out of your home is going to make you feel like you’re a part of the world rather than a prisoner on Rikers Island. And that’s going to help you feel like you don’t need to get loaded, or maybe have two drinks instead of eight, or maybe watch a movie, read a book, and fall asleep gently, wondering about the mysterious mix of chance and destiny that’s landed us in this crazy time. Together.

………………………..

If you haven’t yet, please visit and maybe subscribe to my YouTube channel. It’s new, and it features videos of my talks and interviews over the past few years. No spam or junkmail of any kind, I promise.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments