1. Shame and addiction: a personal window

We frequently hear about the intimate relation between addiction and shame, and many of us have experienced it. But what is the subjective feeling of shame that makes it not only very unpleasant but a potent trigger for further substance use? Today I want to explore my own experience of shame and get down to a description of the feeling itself. What is this feeling that we shun, and why does it make us crave more of whatever we’re addicted to?

I studied emotion for many years. According to the books, emotions are experienced in several ways: there is a bodily constellation, perhaps made up of muscle, organ, and joint tensions sending signals to the brain; there is a physiological signature, a specific pattern in the autonomic nervous system; and there is an action tendency, a readiness or an urgency to act in a certain  way, to retreat in fear, attack in anger, and so on. The action tendency evoked by shame may be the urge to hide the self. But there is also a purely mental state corresponding with each emotion, a state that might be called the feeling itself. That’s what I want to explore.

way, to retreat in fear, attack in anger, and so on. The action tendency evoked by shame may be the urge to hide the self. But there is also a purely mental state corresponding with each emotion, a state that might be called the feeling itself. That’s what I want to explore.

Shame is one of the seven or eight basic human emotions. If you’re human, you know how shame feels. But that doesn’t mean you spend a lot of time bobbing in states of shame. Shame is one of the most painful emotions, matched only by profound sadness. Because it is so aversive, we do whatever we can to avoid it or to terminate it once it’s arrived. Very often shame leads directly to anger. Why? Because whether in reality or in imagination, someone has shamed us. Usually a parent or an authority, or someone who reminds us of those figures in our past. Or a lover, someone we reach toward who then spurns us. Shame can be triggered by being shunned or rejected when we are feeling open or vulnerable. Or simply by being observed doing what we’re not supposed to do. But knowing the triggers of shame doesn’t get to the essence of the feeling and the impact of that feeling on our consciousness.

The evolutionary purpose of shame is clear, and it reveals a connection between the human mind and the minds of other animals. Dogs, for example. Shame shapes how we behave in most or all social situations. Parents (or other “mentors”) use shame, often without ill intent, to punish bad behaviour — behaviour that can easily get the child in trouble outside the safety of the nest. And because we’ll do anything to avoid shame, it usually works. The trouble with shame and addiction is that the purpose of shame has been badly distorted, skewed off in a totally unproductive direction. Like cell growth in cancer, shame related to drug use evokes more, not less, of the destructive activity. Why is that?

Last night I had an argument with my wife. Isabel and I have been together for 24 years, and our marriage is generally peaceful and happy. But of course all intimate relationships include episodes of conflict. It wasn’t really very serious. She said something that hurt my feelings, made me feel small, inadequate, and objectionable, when I felt open and loving. That’s all it took.

So instead of letting the feeling pass or doing my best to chase it off, I lay in bed last night trying to identify the essence of this emotion. It wasn’t that hard. The feeling was one of churning or gnashing of my insides. It was a feeling of being shredded or ground up — inside my own body, and that’s the main point. I remembered my days of addictive drug use, and I suddenly understood why  shame occupies a loop that both emanates from and returns to the urge to get high. The first half of the loop is clear enough. Using drugs addictively is universally shunned because it epitomizes the loss of control, sometimes viewed as self-indulgence or hedonism. But the second half of the loop is more mysterious.

shame occupies a loop that both emanates from and returns to the urge to get high. The first half of the loop is clear enough. Using drugs addictively is universally shunned because it epitomizes the loss of control, sometimes viewed as self-indulgence or hedonism. But the second half of the loop is more mysterious.

The shame induced by drug use feeds right back to drug use because getting high — changing the way it feels to be inside your own body and mind — is a highly effective way to cancel out shame. To feel ground up and savaged inside…that’s a feeling that’s intrinsically hard to escape. Because it’s your insides that are fragmenting. What keeps shame in place is the thought that you really are despicable, undeserving of being who you are. The thought “I am despicable” is pervasive because it’s a belief you accept and endorse, deliberately or not, a conclusion that arises from your own opinion of yourself, no longer from the actions of others. And as soon as you start to think, I need to get high (or drunk or stoned or fucked or whatever it is), then the ammunition for self-deprecation rises to the surface. You are despicable, indeed, because all you want to do is more of the bad behaviour.

There’s really only one effective solution for shame, and that is to be comforted, soothed, loved — reconnected with someone who cares for you. But because addiction draws us away from others who might care, this solution becomes increasingly remote. I’m completely in sync with Johann Hari’s famous mantra: “The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety — it’s connection.” Well the opposite of shame isn’t pride; it’s also connection. That’s no coincidence.

If you want to read some philosophical writings about addiction and shame, check out Owen Flanagan. I think he’s the acknowledged master, and his writing is both accessible and powerful.

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary,

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary,  bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive.

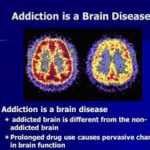

bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive. For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption.

For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption. Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances.

Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances. The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity.

The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity. sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms.

sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms. struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited

struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited  opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility.

opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments