Part 2. Demons, delusions and directions for change

I have not posted anything on this blog for over three months. I sometimes feel I’ve said all I have to say about addiction, and now is one of those times. But new ideas come in clusters. It’s hard to know whether and when a new cluster is about to pop up. Maybe it’s now. Anyway, if any of you were concerned, my family and I are fine. Radio silence doesn’t mean I’ve disappeared.

For now I’ve got a couple of guest posts ready to go, and I think they’ll be of interest to you. The first is from our old friend Shaun Shelly, whose March 6th post stirred a fair amount of controversy. Here’s Part 2. Get ready for more controversy — and directions for how to clear the air.

…By Shaun Shelly…

Previously I argued that “drugs” are essentially a construct that defies any straightforward, objective designation or referent. Some felt that my point was mere semantics and that the drugs I referred to were indeed harmful. To minimize confusion, let me clarify that I was pointing to drugs that are often (not always) illicit or unregulated and thought to be addictive. I quoted Derrida who said “the concept of drugs is not a scientific concept, but is rather instituted on the basis of moral or political evaluations: it carries in itself both norm and prohibition…it is a decree, a buzzword.” Here I’ll use the term drugs in italics to refer to this hard-to-define category.

So, onward: If there is no empirical definition of drugs, what are we hoping to achieve when treating “drug addiction”? In this post, I argue that a value-neutral and rational understanding of drugs would save lives and change our response to the use of drugs for the better.

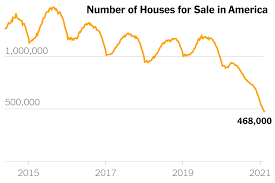

The opioid crisis in the USA gives an excellent example of how the impact of a moral and disease-laden framing of opioids plays out. The combination of an economic crisis, the loss of jobs, increasing inequity, the housing crisis, the increased cost of education and little chance for resolution made people vulnerable to anything that gave them some relief from the pain of their existence, lack of hope and sense of impending failure.

The opioid crisis in the USA gives an excellent example of how the impact of a moral and disease-laden framing of opioids plays out. The combination of an economic crisis, the loss of jobs, increasing inequity, the housing crisis, the increased cost of education and little chance for resolution made people vulnerable to anything that gave them some relief from the pain of their existence, lack of hope and sense of impending failure.

Widespread emotional and physical pain combined with direct end-user advertising of opioids and increased prescribing made the rise in opioid use predictable. Opioids filled the gap, as did Trump. Another critical contributing factor was the message that opioids are highly addictive. People believed that using an opioid would make you addicted and, once addicted, your life would

Widespread emotional and physical pain combined with direct end-user advertising of opioids and increased prescribing made the rise in opioid use predictable. Opioids filled the gap, as did Trump. Another critical contributing factor was the message that opioids are highly addictive. People believed that using an opioid would make you addicted and, once addicted, your life would  spiral out of control. The narrative became a self-fulfilling prophecy. People prescribed opioids started overdosing, by exceeding the correct dose or mixing their opioids with other medications and/or alcohol. Then heroin began to be contaminated with fentanyl. Fentanyl is many times stronger than heroin and was often undetected. People who used heroin began to die from drug poisoning due to fentanyl contamination.

spiral out of control. The narrative became a self-fulfilling prophecy. People prescribed opioids started overdosing, by exceeding the correct dose or mixing their opioids with other medications and/or alcohol. Then heroin began to be contaminated with fentanyl. Fentanyl is many times stronger than heroin and was often undetected. People who used heroin began to die from drug poisoning due to fentanyl contamination.

The response, informed by the prohibitionist narrative, was predictable: the aim was to eradicate the drug, cure the disease, get people ‘clean’. The CDC placed restrictions on prescribing opioids. Doctors cut people off from their essential pain medications, and the DEA increased inspections of doctors prescribing opioids.

The response, informed by the prohibitionist narrative, was predictable: the aim was to eradicate the drug, cure the disease, get people ‘clean’. The CDC placed restrictions on prescribing opioids. Doctors cut people off from their essential pain medications, and the DEA increased inspections of doctors prescribing opioids.  Information about the addictiveness of opioids and the consequences of the disease of addiction dominated the headlines. Predictably, people began to access pharmaceutical drugs from the street. When those ran out, they did the previously unthinkable and started to use heroin. When cut off from opioids, some pain patients could not live with unbearable pain and committed suicide.

Information about the addictiveness of opioids and the consequences of the disease of addiction dominated the headlines. Predictably, people began to access pharmaceutical drugs from the street. When those ran out, they did the previously unthinkable and started to use heroin. When cut off from opioids, some pain patients could not live with unbearable pain and committed suicide.

If the response had been value-neutral, we would have had a very different outcome. Many deaths would have been prevented. The rational response, in a world without the rhetoric of drugs would have been:

If the response had been value-neutral, we would have had a very different outcome. Many deaths would have been prevented. The rational response, in a world without the rhetoric of drugs would have been:

With the increase in prescribing and dependence, the CDC would:

- Not reduce the supply of regulated opioids.

- Ensure additional training of physicians.

- Ban all direct-to-consumer advertising.

- Ensure the marketing of drugs to doctors was not incentivised but based on data.

- Ensure that people dependent on opioids have an uninterrupted supply of regulated opioids so they would not have to switch to unregulated opioids.

With the increase in fentanyl-related poisonings, policy-makers would:

- Lower the threshold for agonist-prescribing services (methadone programs).

- Ensure that people dependent on heroin (diamorphine) have a regulated, unadulterated supply of diamorphine via community services or retailers.

- Make fentanyl tests widely available to all drug sellers and consumers.

- Analyse heroin samples contaminated with fentanyl and identify the source.

- To ensure immediate broad access to naloxone.

- To promote the passage of federal Good Samaritan laws.

- To distribute factual information and data.

To access networks of people who use drugs, social media and first-responder reports to map contaminated drugs and distribute information about risk areas.

To access networks of people who use drugs, social media and first-responder reports to map contaminated drugs and distribute information about risk areas.- To divert funding used for the DEA and supply reduction to community-based services and support for all community members.

- To decriminalise the use and possession of drugs for personal use.

Tragically, the ‘opioid crisis’ has not motivated policy-makers to take logical measures to prevent further death and suffering. By thinking that drugs like opioids are ‘bad drugs’ and must be prohibited, rational options are beyond consideration. In a rational world, we would realise that the opioid crisis, most addictions and the negative consequences of drugs are not caused by the drugs themselves. Instead, they are the symptoms of our society’s misguided beliefs and policies.

Trying to stop drug use and eradicate drugs are futile pursuits. Instead, we must modify or eliminate the policies, practices and beliefs that cause harm and suffering for certain people who use certain drugs. I long for a world where people can, most of the time, make informed decisions about the what, where, when and how of using or not using drugs, especially drugs, without the threat of arrest, pathologisation, medical maltreatment and social or economic isolation.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments