Praise for Memoirs of an Addicted Brain

“Developmental neuroscientist Lewis examines his odyssey from minor stoner to helpless, full-blown addict….as [he] unspools one pungent drug episode after another, he capably knits into the narrative an accessible explanation of the neural activity that guided his behavior. From opium pipe to orbitofrontal cortex, a smoothly entertaining interplay between lived experience and the particulars of brain activity.” Kirkus Book Reviews

“Memoirs of an Addicted Brain…takes on all of human longing. Unlike many of his brain science colleagues and fellow addicts, Dr. Lewis can write. One moment, he is remembering the details of his life as an addict; the next, he is reconstructing, based on newer scientific findings, what the drugs were doing to his brain. The result is not just a book about a brain on drugs, but a picture of addiction as an unavoidable urge of human nature.” Ian Brown, Globe & Mail

“An engrossing and vividly written swirl of raw personal drama, themes of despair, loss and triumph, brilliantly rendered brain science, and clear thinking on the experience and essence of addiction. Illuminating even to experts, accessible to all.” Gabor Maté, MD, author of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

“Great writers create new genres, and that’s exactly what Lewis has done in writing the memoir of his addicted brain. It’s a heartwrenching story, beautifully written, and no one should be allowed to pronounce about addiction without having read it.” Evan Thompson, PhD, Professor of Philosophy, University of Toronto

“Lewis teaches us how normal yearnings and strivings can be short-circuited by drug addiction. In the end, his triumph is remarkable, and not only because he emerges from serial addictions to become a successful neuroscientist. He also recorded his young life with such perceptiveness, and recounts it for us now with such vividness, that his analysis of brain mechanisms comes alive in a way that is unprecedented in modern literature.” Prof. Don Tucker, Department of Psychology, University of Oregon

“Dr. Lewis has captured how our brain systems make our realities and how our realities buffet our brain systems. He presents a clear explanation of the horror and self-destructiveness of mind-altering drug use, of the drug addict as victim of inner and outer pressures and demons, and of the evolutionary strengths of our brain gone awry.” Prof. Sid Segalowitz, Department of Psychology, Brock University

“This is a splendid, moving, and highly informative book on drug addiction, described from the inside of the mind as well as from the inside of the brain. It is written very well by an expert on both perspectives.” Nico H.Frijda, PhD, Emeritus Professor of Psychology, University of Amsterdam

“Marc Lewis vividly conveys the alluring yet dangerous universe of mind-altering drugs and the painful paths of addiction and recovery. His experiences with LSD, heroin, and other powerful chemicals are woven together with clear explanations of the brain mechanisms underlying drug effects and addiction. Beautifully crafted and illuminating on multiple levels, this is a book you won’t want to set down.” Kent Berridge, PhD, James Olds Collegiate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Michigan.

“Memoirs of an Addicted Brain may be the most original and illuminating addiction memoir since Thomas De Quincey’s seminal Confessions of an Opium Eater. What makes it such a standout from the genre’s overflow of self-indulgent mediocrities isn’t merely its supple intelligence and subtle style but the unique perspective of the author.” TheFix.com

“Memoirs of an Addicted Brain makes a valiant effort to be both diary (of a misspent youth) and textbook on the neurology of drug addiction.” Winnipeg Free Press

“Opponents of addiction memoirs complain that the attention- grabbing genre is tapped out…Cannily, in Memoirs of an Addicted Brain, Marc Lewis mixes the tried and true with a novel approach–a primer on the neural chemistry of addiction…The long fall and gradual recovery is an inherently appealing story, and Lewis tells it well. And for genre skeptics, Lewis supplies a surplus of educational material.” Vancouver Sun

“[Memoirs of an Addicted Brain] is compelling, and for readers grappling with addiction, Mr. Lewis’s mechanistic approach might well be novel enough to inspire them to seek the happiness he now enjoys.” The Wall Street Journal

“Marc Lewis’s Memoirs of an Addicted Brain is a cracker…The science is up to the minute. Lewis clearly knows his stuff.” The Australian

“As strange, immediate and artfully written as any Oliver Sacks case-study, with the added scintillation of having been composed by its subject.” The Guardian (UK)

“A surprising and charming addition to this crowded genre.” The Boston Globe

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one:

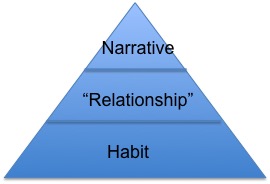

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one: The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and

The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and  conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained.

conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained. secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need.

secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need. Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it. Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments