This is your brain on choice

Let’s return to John’s driving metaphor and fit it with what we know of the brain. As per my last post, let’s look at choice as a blip, a flash of intention, that rides on the momentum of underlying habits. Skillful drivers have built up a repertoire of good habits, like alertness, sensitivity, self-monitoring, and flexibility. So, even though they can’t promise to never have an accident, they can minimize the risk.

“Driving responsibly” like “drinking responsibly” sounds like Big Brother claptrap. In fact driving well is very Zen. Today I took the car out on the winding roads at the foot of the French Pyrenees. I thought about John’s metaphor and became more aware of what I actually do when I’m driving. I took the curves gracefully, skillfully, even though the skill wasn’t something I could put my finger on. It wasn’t something I possessed. Rather, it felt like a moment-to-moment balance between assertion and surrender, focus and flexibility. It had to be that way, because I was moving fast through complex terrain, and I was thinking with my head but also with my body, my instincts, and that vast unconscious part that puts it all together, moment by moment.

This view of choice fits well with brain mechanics. Sensory input pours in from the retina to the occipital area at the very back of the brain. That’s the primary visual cortex. Then it gets passed forward toward the centre of the brain, and it becomes more holistic, more comprehensive, along the way. Stage by stage (but very quickly) it joins with other sensory information (e.g., the feeling of the wheel in my hands) as well as memories and feelings. By the time it arrives at the orbitofrontal cortex, it is a gestalt with a familiar meaning.

At the same time, motor output cascades from the centre of the cortex outward toward the periphery, going through stages in the opposite order. It starts in the dACC, or a region just north of the dACC called the supplementary motor area. That’s where plans seem to emerge. From there the output stream gets increasingly articulated, as it passes through the premotor cortex, where plans are translated into global action patterns, and finally to the motor cortex, where the actual muscle movements are orchestrated.

These streams, input and output, flow at the same time – the output stream doesn’t wait for the input stream to finish before it starts up.(If it did, we’d respond to our environment at the pace of a slug.) So a special trick is needed to coordinate these streams. The brain connects the input stream to the output stream at each level, from detail to gist, with multiple connecting links, like rungs on a narrowing ladder. At the bottom rung, concrete sensory details connect with concrete action commands, so the visual details of a sudden curve in the road are coordinated with the movements of my hands on the wheel. The rungs continue to connect the two pathways, as they get closer to the centre of the cortex, where a meaningful visual scene connects with a meaningful motor plan: I’m driving this narrow winding road, which feels good, but a car could come around the corner at any moment so I’ll downshift to second gear and slow down. Which I do.

Intention – where “I” make a voluntary choice – is a difficult thing to locate in the brain. But our best guess is that it happens near the centre of the cortex, where orbitofrontal meaning connects with emerging plans in and around the dACC.

So choice takes up a rather small part of the whole sensory-motor process. Think of it as the top rung of the ladder, with all the other rungs stretched out below it, doing their business of integrating perception and action. Was it a choice to change gears just then? Certainly. But that choice was the cream at the top of a dark, frothing mixture of perception and action at multiple levels. And what about those links below the level of choice? They are automatic, unconscious, and they are shaped and refined through repetition, through learning. Those links are where habits get built, by way of synaptic shaping, and those habits determine a very large part of our behaviour.

Driving is a great metaphor for how we negotiate the attractions and hazards of life, which is also complex and difficult, and which also comes at us around each corner with great speed. Driving relies on something like flow, but flow depends on smoothly running habits. Being a good driver requires good habits, to give choice a chance (paraphrasing John Lennon). Being a good ex-junkie or ex-drunk also requires good habits, if you’re going to stay on track. First we try to build up those habits, then we simply do our best to make good choices, whenever the road takes an unexpected turn.

Choices are based on appraisals (interpretations) of situations. People with addictions choose whether to get high or abstain based on appraisals of the quality of the high, the consequences of indulging, the proximity of other people who might approve or disapprove, and so forth. Since our appraisals are determined by factors outside our volition or awareness, especially in a complex situation changing moment by moment, the choice we make in that situation is less determined by our volition and more determined by luck and circumstance.

Choices are based on appraisals (interpretations) of situations. People with addictions choose whether to get high or abstain based on appraisals of the quality of the high, the consequences of indulging, the proximity of other people who might approve or disapprove, and so forth. Since our appraisals are determined by factors outside our volition or awareness, especially in a complex situation changing moment by moment, the choice we make in that situation is less determined by our volition and more determined by luck and circumstance. Appraisals are also strongly affected by internal variables: mood states, present emotions, beliefs, (biased) recollections of previous events. But this list doesn’t yet scratch the surface. There is my sense of emptiness and dislocation at this moment, compared with how I think I’ll feel after getting high, compared with how much drug I possess or can afford, in the context of building excitement and/or building anxiety and shame. These “internal state variables,” as psychologists call them, are highly complex and they change from moment to moment. Since that mix of factors will certainly affect one’s choice (e.g., to use or abstain), I can’t see how the choice can be entirely voluntary, entirely an expression of “free will.”

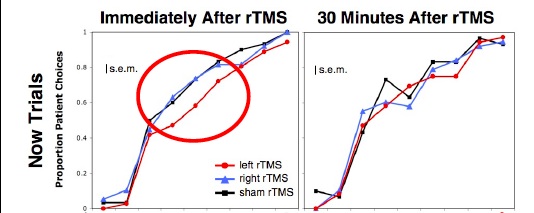

Appraisals are also strongly affected by internal variables: mood states, present emotions, beliefs, (biased) recollections of previous events. But this list doesn’t yet scratch the surface. There is my sense of emptiness and dislocation at this moment, compared with how I think I’ll feel after getting high, compared with how much drug I possess or can afford, in the context of building excitement and/or building anxiety and shame. These “internal state variables,” as psychologists call them, are highly complex and they change from moment to moment. Since that mix of factors will certainly affect one’s choice (e.g., to use or abstain), I can’t see how the choice can be entirely voluntary, entirely an expression of “free will.” cannot suddenly be imported into a system that has none. Changes in appraisal, emotion, and social factors strongly influence volition, which influences actions, all of which alters one’s belief in oneself — one’s self-efficacy. That’s why self-talk and help from other people

cannot suddenly be imported into a system that has none. Changes in appraisal, emotion, and social factors strongly influence volition, which influences actions, all of which alters one’s belief in oneself — one’s self-efficacy. That’s why self-talk and help from other people  (friends, partners, books, stories, podcasts) can be so important. Once addicts tune into the possibility of volitional choices, the mechanism underlying volition itself grows in strength and availability.

(friends, partners, books, stories, podcasts) can be so important. Once addicts tune into the possibility of volitional choices, the mechanism underlying volition itself grows in strength and availability. is available during the impulsive phase of addiction, as one’s imagined future slides down a sort of chute into the “now”? Some, I think, but not much. Once the compulsive stage of addiction is reached, how much volition is present? Now action is put in motion before one is even aware of making a choice. Still, compulsion is not abnormal or pathological. When we examine more mundane decisions, like whether to check that the stove is turned off, it’s clear that volition and compulsion mix together, competing and cooperating, as we make choices. It’s not mandatory to recheck the stove.

is available during the impulsive phase of addiction, as one’s imagined future slides down a sort of chute into the “now”? Some, I think, but not much. Once the compulsive stage of addiction is reached, how much volition is present? Now action is put in motion before one is even aware of making a choice. Still, compulsion is not abnormal or pathological. When we examine more mundane decisions, like whether to check that the stove is turned off, it’s clear that volition and compulsion mix together, competing and cooperating, as we make choices. It’s not mandatory to recheck the stove.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Recent Comments